The magic of Loom

Why I Love: Eidos Montreal's Rayna Anderson explores how LucasFilm Games bucked convention for a project that "felt like a conversation with the game's creators"

Why I Love is a series of guest editorials on GamesIndustry.biz intended to showcase the ways in which game developers appreciate each other's work. This installment was contributed by Rayna Anderson, senior narrative designer at Deus Ex: Mankind Divided developer Eidos Montreal.

If you've ever asked me what my favourite game is, you've probably gotten many answers over the years. But lately, 1990's Loom has risen to the top and I have finally figured out why my appreciation of the design of this simple point-and-click adventure continues to grow.

The game opens by welcoming you into the world. The kind, grandmotherly narration is set over the soothing orchestration of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake. This opening isn't foreboding or intended to set your nerves on edge like other games that came before it. Instead, it tells you to relax, settle in, that everything is ok. The mission you're given isn't to destroy something or kill someone, but to amass knowledge, help others, and rejoin your family.

While the mystery of what's happening in this world feels large, your motivation to move forward remains personal.

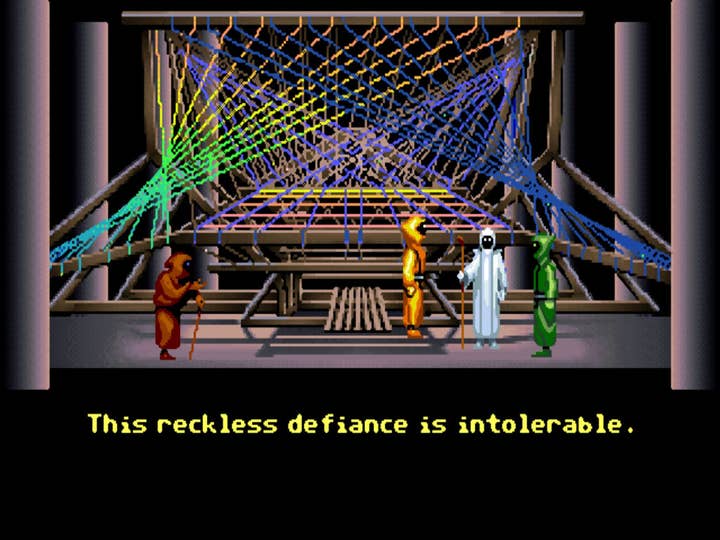

And with that, you're released into this unique world where magic does ordinary things for ordinary people. I still appreciate the story's brand of magic, which doesn't involve fairies, or elves, or wizards. Magic is musical, woven into the very fabric of life. There aren't ancient, forbidden tomes to learn this magic from. You learn it by observing it in the natural world and the actions of its inhabitants. In Loom, rewards are received for passively watching life unfold.

The game also rewards you for being clever with how you use the magic you've learned. Each problem has several solutions and you're never punished for experimenting. Unlike many adventure games from this era, Loom has no dead ends, no unsolvable puzzles. What the game expects you to do is always clear and the puzzle solutions are always logical.

"Reaching the end of Loom was an experience that brought with it a new feeling that I'd never felt playing a game before: resolution"

In fact, I was surprised when, just a few hours later, it was done. I didn't die or hit a dead end; I completed the game. No way had I ever gotten anywhere close to finishing Maniac Mansion! We're talking very early '90s here. There was no internet, no walkthroughs. If you got stuck on a game, the best you could hope for was another nerd friend with "lateral thinking" abilities. Reaching the end of Loom was an experience that brought with it a new feeling that I'd never felt playing a game before: resolution. This was not the satisfaction of having 'won', but the feeling that Bobbin's story was over and his inevitable ending earned. I walked away from it enriched by the experience.

Since then, other favourites have come and gone, those that are innovative, exciting, or compelling. But my love for Loom has continued to grow over the decades. As a player and designer I think about it often, and I finally understand why I enjoyed it.

The majority of games, especially back in the '80s, are confrontational. They tend to be a challenge between the designer and player to see who can be smarter. They got harder and harder until you ran out of quarters, died, or glitched out. Or, if you did get to the end before your mom unplugged your console, you got a single title card congratulating you for conquering the toughest challenge yet. Then, unceremoniously, your quest was over. Finished. Complete. And you, the developer assumed, should be pleased with that accomplishment alone.

Loom was the first game that I experienced in its entirety. And it's stayed that way in my memory: a complete experience. In an age of confrontational games, Loom was the first to invite me to experience its entire vision, from start to finish. It felt like a conversation with the game's creators. I wasn't taunted to prove myself with memorization or motor-skills. Loom encouraged me to see their story, to participate in the transformation of Bobbin and his world. Their game presented nothing to block me from consuming it whole.

This is why I've been so enamoured with the recent boom of walking sims. I don't need endless hours of trying to outwit the devs to see what the meaning of the game is. Walking sims don't want you to experience the first hour, with some sections on repeat until you can master them. They want you to play through the whole game so you can understand the creator's intent. It's the journey that's the message, and without reaching the end, the message is incomplete.

Loom may be a short experience, but what I continue to learn from it will last me a lifetime.

Upcoming Why I Love columns:

- Tuesday, February 13 - Ghost Story Games on DOTA 2, Doom (2016), Final Fantasy X, Kerbal Space Program, and Final Fantasy XIV

- Tuesday, February 27 - Caledonia's Nels Anderson on Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice

- Tuesday, March 13 - Auroch Digital's Tomas Rawlings on Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty/Battle for Arrakis

Developers interested in contributing their own Why I Love column are encouraged to reach out to us at news@gamesindustry.biz.