Notes on inspiration from a BAFTA-winning studio

Sarepta Studio's CEO Catharina Bøhler explores the many ways to find inspiration and stay creative during development

When working on a game project for several years, it's only natural to hit dead ends occasionally. That can affect both the technical and creative aspects of development, and it can be hard to pick yourself up when going through a difficult period. The issue can be particularly problematic in small teams that don't benefit from the support and resources of a wider network.

How to stay creative during development is the topic that Sarepta Studio's CEO Catharina Bøhler chose to tackle during a Ludicious X talk last week. Exploring the challenges, emotions and group dynamics at play, she provided ideas for how to work with various sources as inspiration, and talked about how the studio shapes the vision for its games.

"Sarepta Studio focuses on emotionally impactful and atmospheric games," Bøhler said. "We of course work with a lot of gameplay, but the interactions are inspired by a story or theme. So that is why my talk will be very narrative-centric."

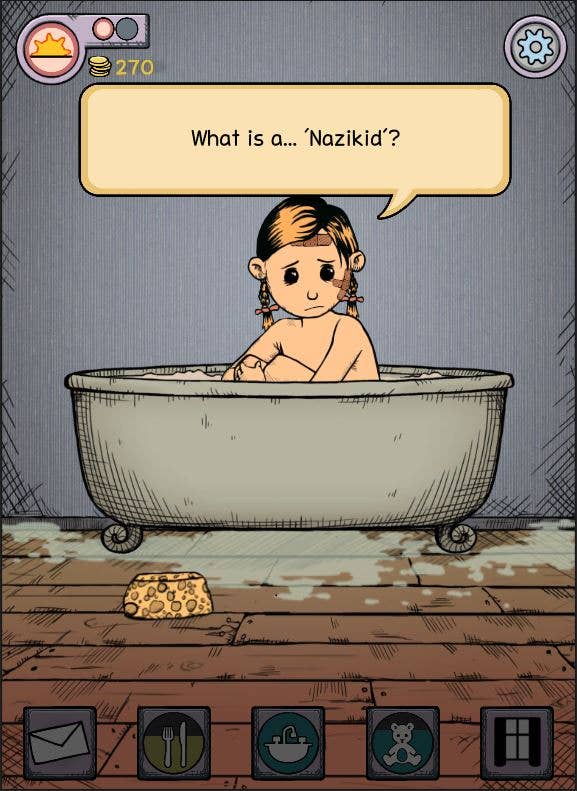

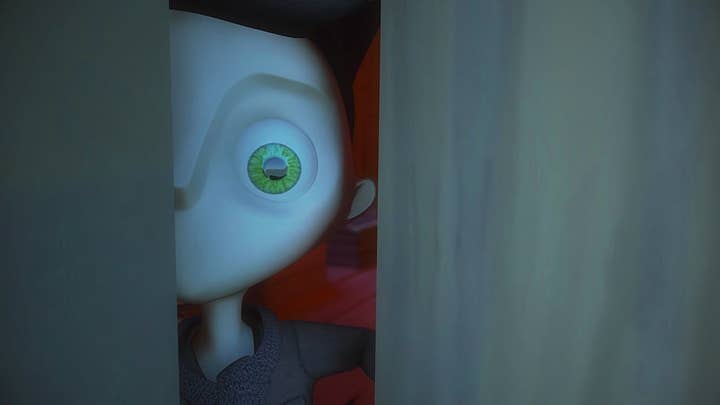

During her talk, she relied on examples from the developer's three games. The Norwegian studio's first title was Shadow Puppeteer, an atmospheric co-op adventure about a boy and his shadow. Then came the BAFTA-winning game My Child Lebensborn (created in collaboration with Teknopilot), which Bøhler described as a "parent simulation game," exploring the story of children born of war in Norway. Finally, she touched upon the studio's current production, Project Thalassa, a first-person drama about a deep sea diver in 1905.

Limitations as inspiration

All projects at Sarepta Studio start the same way: the team clarifies the frame they will work within.

"[We] identify a market, potential for income, brand developments, strengths and weaknesses of the team, and the potential scope," Bøhler explained. "Based on this frame, we identify our internal guidelines. Some might see these requirements as something that bogs down creativity, but I find it more helpful to think about how the limitations can be used to help think differently."

"I find it helpful to think about how limitations can be used to help think differently"

Identifying potential limitations will force you to double down on the creativity -- if you leave the scope open, you may end up with a frame of referjavascript: Eurogamer.markup.toggleStyle('pages[1]', 'quote', 'egcml');ence that's so large that it will dilute your vision. If you identify limitations, these will feed your approach throughout the entire development process.

"For Project Thalassa, we got inspired by stories of deep sea divers, but the topic of trauma and loss became a bigger part of the vision and we started going down a very narrative route," Bøhler said. "Talking with advisors, it was made clear to us that making a fixed narrative single-player game had many risks. A prevalent one is that it often can be easier for people to just watch a playthrough rather than purchase the game. So we took this to heart and looked at minimising these risks. It inspired us to center the game more around the player's perceptions and choices."

Another type of limitation could be the size of your team versus what you're hoping to accomplish. If you're only a handful of people, you probably won't be able to write 100 characters to populate your world. So what alternative can you come up with that would help your world feel populated? Thinking in terms of limitations can force you down a path you wouldn't have explored otherwise.

For My Child Lebensborn, Sarepta had to work with another limitation: the game tells the true stories of some of the Norwegian Lebensborn children, which means it had to be historically accurate.

"This added a lot of extra work and limited our possible mechanics," Bøhler said. "Although it does make the process more time consuming, limitations like these could help boost your creativity. It really helped us think differently."

On its dev blog, Sarepta detailed an example: a rubber duck that the child could play with during bath time, but it ended up having to change plans as these did not exist in 1951.

World building as inspiration

One way to circumvent a creative block is to go deeper on your world building. Creating lore can help you uncover a direction for your game that you didn't think about in the first place.

"We tend to create quite a lot of [backstory] even though the player most likely won't end up seeing it," Bøhler said. "The game where we experienced this the most was Shadow Puppeteer. There are only three main characters -- the character you play, the boy in the shadow, and the villain.

"Because the villain is an important driving force in the game, we wanted to understand his backstory and what his motivations were. In the end we made so much backstory for him, but only actually hinted at it towards the very end of the game. It was quite a dark turn so many were understandably surprised. But the response was really good and we never would have thought of such a dramatic ending if we hadn't decided to learn more about our villain."

Research as inspiration

While this approach worked well for Shadow Puppeteer, things are not as easy when working on games set in the real world. Bøhler pointed out the feeling of uncertainty the team faced when working on difficult topics, feeling stuck when facing questions that can be hard to answer.

"Like why wouldn't the parents of Lebensborn do something about this situation? And, when adopted, how would someone feel about their biological parents? How does trauma affect children? When I get stuck like that, I need to learn more," Bøhler said.

"Being informed helps us make the right choices during the design process"

That's where a more pragmatic approach needs to be taken, through traditional research. Sarepta conducted interviews with Lebensborn children, read about child psychology, and watched documentaries about adoption. For the most difficult themes, the team talked to an expert about child abuse.

And while that may not sound like groundwork for creativity, it absolutely is, Bøhler argued.

"Being informed helps us make the right choices during the design process -- learning about new things helps form new ideas. For Project Thalassa, we have a wide cast of characters that we do research on but the biggest challenge was trying to understand what life must have been for our female characters in 1905.

"What would a female adventurer go through and were there even female adventures back then? This game is not aiming to be a 100% historically correct, but we still wanted it to be plausible. It's better for our team's inspiration and motivation. I was very relieved to find evidence of female divers in London in the early 1900s."

She pointed out that research doesn't have to be expensive nor time consuming.

"Even just an evening of searching the web or 20 minutes chatting with someone who knows of your topic can actually help quite a lot. You can do extensive research on the internet, find books, sites, films and the like. I usually just start browsing and create a large list of resources to look into. I also create a list of potential advisers to talk to.

"You can check your libraries, archives, online museums -- and whether that's people in your team who might have relevant experiences, friends, grandparents or specialists, talking to other people is very helpful. When things get safer, you could also travel.

"Whatever really is relevant to your setting, story and theme, you should try to find some way of learning more about it. And with so much material being available, there's no reason not to do research. Personally I find it extremely helpful in getting a sense of the game I'm making."

Emotions as inspiration

Developers also shouldn't underestimate their gut feelings. Some central aspects of Sarepta Studio's games were decided solely on the fact that it "felt right," Bøhler explained. Not everything needs to be led by an underlying principle.

"In Shadow Puppeteer, we had no dialogue, no text. It was a guideline I made early on and I actually had trouble justifying it. We used music and environment to tell the story and convey emotions, which really helped the overall atmosphere. We ended up not giving the main characters mouths.

"In My Child Lebensborn, we don't want you to see the other people. Looking at these people who hate your child just didn't feel right. Either they would look too normal or too much like caricatures. So we scribbled over their faces. And it became a powerful way of expressing an ugly situation and the uneasiness that the child feels.

"Then there's Project Thalassa -- it will be a bit odd but we just don't want the player to hear the voice of their character. We're still having some challenges justifying the idea to the team, but we believe that it will fall into place eventually and we can use it to emphasize our vision."

Letting some aspects of development be driven by emotion also means not being afraid to leave blank spaces for players to project their own feelings.

"If we can, we strive to leave things unsaid," Bøhler said. "It's a lot more satisfying to connect the dots than being told everything. One of the major emotional guidelines that we set for My Child Lebensborn was connected to leaving a blind space for the player. Early on, we decided that you won't see the bad things that happen to your child in the game. The idea of writing it and making you see it just didn't feel right.

"This choice created a huge restriction which inspired a narrative style that allowed us to go into some topics that we really wouldn't have been able to otherwise. Instead of showing what happens to the child, you see the aftermath."

Players as inspiration

Thinking about how the player is going to interact with what you're creating is also a driving force that should maintain your creativity throughout development. And it may impact unexpected aspects of your game, such as the platform you're releasing it on.

"What we want the player to feel is a large focus and it inspires most of the things that we do"

"What we want the player to feel is a pretty large focus and does inspire most of the things that we do," Bøhler said. "With My Child Lebensborn, it's very important to have the player connect to the child instantly. The great thing is that mobile, with its touchscreen, is a very intimate platform.

"For Shadow Puppeteer, we took into consideration how people would be playing together on their couch, connecting and growing together, sharing defeats and successes."

Other games as inspiration

Finally, it's crucial that you look at what's being done elsewhere in the games industry -- it can be particularly enriching if you've reached a dead end with your project.

"Obviously I'm not saying that you should [steal] other people's [ideas]," Bøhler said. "What I'm talking about is analysing other games that do similar things that you want to try to do, or evoke emotions that you want to, and understanding their strengths and pitfalls."

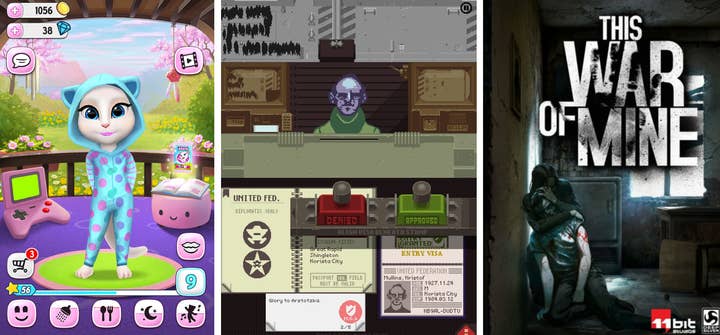

And it doesn't have to be games that are in a similar genre. For My Child Lebensborn, Sarepta Studio found inspiration in unexpected places.

"Looking at My Talking Angela made us gain a better understanding of the current nurture genre. A game such as Papers, Please showed us that even a disconnected family could actually be something you care about. This War of Mine proved that even desperately depressing games can be very engaging."

Looking at other games for inspiration can also help you find general mechanics that can work for your project. Sarepta Studio is quite disciplined in its approach.

"For a workshop on animation and interaction, we were five people in the team sitting together for five hours playing and analysing six different games," Bøhler said. "We set up eight categories, analysed these in the games and then made decisions on what approach we would want.

"When we need to make major decisions, we often have smaller work groups that then present their decisions to the team so that the team gets a chance to challenge or point out flaws. For many of the game design or narrative elements, we have a group of two or three people who then create guidelines and share them with the team.

"Not knowing when you are right and when you are failing horribly is the charm of game design"

"We also do completely open brainstorms and vision workshops with the whole team to make sure that we're on the right path -- [that] spark new waves of creativity in everybody."

Ultimately, listen to your team -- your colleagues may be your greatest source of inspiration and creativity.

"Something that's really helpful is to share everyone's thoughts of: what about the game excites them? It helps to emphasise the project's strengths and perhaps highlight some weaknesses. If the things that you are excited about are not the same as your team, then you might not have communicated the vision well enough.

"One important thing that we weren't doing enough of at the beginning was to sit down with the team, go through and confirm the game's major guidelines, to make sure that everybody could agree. Setting aside some time to battle it out to at least get a general consensus of: yes, we believe that this could be the right thing to do."

She highlighted two important things to remember when going through such a process. One is that you need to allow yourself to be challenged and potentially drop your idea, and the other one is the opposite: be ready to defend your idea.

"Not knowing when you are right and when you are failing horribly is the charm of game design," she said. "What's important is to have a good dialogue within the team, to have such trust in each other that you can dare to go into discussions even though you know it's gonna get heated."

The GamesIndustry.biz Academy guides to making games cover a wide range of topics, from finding the right game engine to applying for Video Games Tax Relief, to the best practices and design principles of VR development, or how to improve your world building. Have a browse.