How to design for coziness...and kindness

Tanya X. Short, Rebecca Cordingley, and other developers of "cozy" games explain why and how they make their games safe, familiar and intimate

Fuzzy socks. Cats in laps. Being wrapped in blankets by a fire while a storm rages outside. At an evening panel at PAX West 2018 called "Creating coziness in game worlds," I was inundated with such images from the creators of some of the coziest games around - all of whom, unsurprisingly, like to make themselves cozy when they settle in to work in their respective projects.

Alongside the panel, GamesIndustry.biz caught up with a few of the panelists after the fact to discuss cozy game design further. Throughout both the panel and these discussions, a common thread that kept coming up was the correlation between "cozy" games and "kind" games - games that are kind to the player, and that make them feel kind.

For example, when asked what made her interested in making cozy games to begin with, Finji CEO Rebekah Saltsman (Overland developer, Night in the Woods publisher) immediately thought of accessibility.

"If you can engineer anything that allows people to slow down...you're getting much more value out of the expensive assets you use in your games"

Nick Popovich

"Overland is a hardcore strategy game, which is not normally a genre which would appeal to someone like me," Saltsman said. "How do I bring people like me, how do I bring [people] who can't figure out how to use a camera in a game, how can I encourage them to have this incredible depth of play experience? What we've done is remove the barriers of entry so it feels like it's a place I'm supposed to play. For me, that's sort of the definition of cozy. We're welcoming you to experience this thing and tell a story."

Nick Popovich, co-founder of Monomi Park (Slime Rancher), pointed out that designing cozy games is a smart decision, especially for an indie developer on a tight budget.

"You get more bang for your buck," Popovich said. "Most games are driving you to an objective. It's very consumptive. If you can engineer anything that allows people to slow down, make their own fun, grow something, build something, you're getting so much more value out of the very expensive assets you use in your games.

"A lot of people aren't making games like this. Do something different, and you'll get a new market. You'll get people appreciating your games that otherwise wouldn't, and like we found in Slime Rancher, there are plenty of people who play CS:GO all day and then they play two hours of Slime Rancher to end the day. If you offer a positive energy, no one's too good to sit and get cozy in a game or slow down and appreciate it."

The others on the panel also echoed that practical sentiment, and pointed out that developing kinder, cozier games had led to more positive fan interactions. The group jovially argued over who had the best group of fans. "We break their save files every update," said Saltsman, referring to Overland. "No one complains."

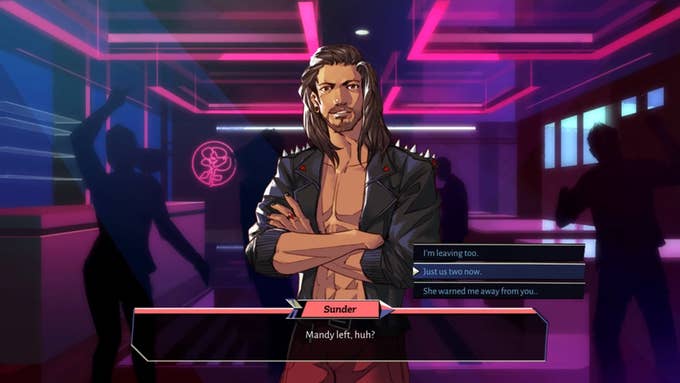

Tanya X. Short, co-founder of Kitfox Games (Boyfriend Dungeon), countered by describing a time when someone emailed her studio apologizing for crashing their game.

"The more cozy a game is, the more I enjoy interacting with my fans," Short said. "Although I enjoy many hardcore games, I think it can be difficult to interact with people who primarily associate you and your games with adrenaline, or challenge, or some kind of personal vendetta...I just think that the people who spend two hours on Slime Rancher are going to treat you a bit differently as a developer."

One other reason these developers focus on cozy, kind games is simply because they personally find it important. Glumberland's Ben Wasser told me that was the drive behind Ooblets; it was simply something he and the game's co-creator, Rebecca Cordingley, wanted to make themselves.

"I don't feel like something is my home just because the game designer says it's my home"

Rebecca Cordingley

"I'd just sort of imagined what kind of game I would like to play," he said. "Sometimes a game would really strike me as my sort of thing, but I'd feel like it was missing something or be made better with bits from another game. Ooblets was my way of trying to mush everything together and fill in all the gaps I'd felt existed in other games."

But what does it mean to make a cozy, kind game? One thing that immediately came to mind for the panel was a game's aesthetics, and most of the cozy games developed by the group include soft textures, bright colors, round corners, and cute characters. But as several of the panelists attested, coziness isn't a synonym for cuteness; cozy games also tend to inspire a feeling of intimacy, they said, of trust and connectedness. Many include mechanics of nurturing and caring, low-pressure environments, and feelings of abundance.

Cordingley talked about the importance of customization in making a game cozy.

"I don't feel like something is my home just because the game designer says it's my home," Cordingley said. "I want to make the home myself. And the avatar, I want to feel at home in my avatar. It's an expensive feature to add so much customization, but I think it adds so many nice feelings to the game."

Short took the idea a step further in our post-panel conversation, discussing the role of customization in making a game feel inclusive and players feel comfortable.

"[Boyfriend Dungeon] is based in an idea of inclusivity, because I felt excluded from a lot of the dungeon crawlers and a lot of the dating sims that are out there," she said. "By trying to make something inclusive, I think if you're being coherent about it, you're automatically going to incorporate elements of coziness, because you want it to be welcoming to as many people as possible.

"Part of it is assuming who you are and what you want and who you want to be friends with. I do have to assume something [about the player] at some point. There is a set-up and a setting. But I don't assume what gender they are, I don't assume how they want to look, I don't assume what genders they want to date or not or have sex with or not.

"For Boyfriend Dungeon, the coziness is a little bit more abstract, but I want the music and the world and the characters to all make you feel welcome, and to make it feel like a place you can relax in. Even if you're dungeon crawling, it's not supposed to be this massively stressful situation."

"You never want the player to be failing or losing simply because they misunderstood the intentions of the developer"

Rebecca Cordingley

On the other hand, elements such as death, violence, time constraints, and other negative experiences can ruin coziness. For example, Cordingley said that Ooblets has no violence whatsoever, all the characters are vegetarian, and Glumberland has a rule that "anything with a face, you cannot eat."

Cordingley and Wasser said they also try to minimize punishments and stressors, but sometimes run into situations where they need to find creative ways to avoid boring or repetitive gameplay as a result.

"We really put a lot of thought and iteration time into usability, and that goes a long way to removing a layer of frustration," Cordingley said. "You never want the player to be failing or losing simply because they misunderstood the intentions of the developer. We also try to avoid anything that requires the player being super adept at using a controller or having quick reactions."

That said, Spry Fox's Daniel Cook finds that darker elements can bring a feeling of intimacy or coziness when used in the right way, such as with the coziness of the bonfire in Dark Souls or, in the case of his game Alphabear, a cute bear saying terrible things.

"There's part of human psychology where as we become friends with people, we gain intimacy with them," Cook said. "And as we become intimate with people, we disclose the more negative aspects of our personality. Close friends will often be a bit crasser and ruder with one another because it's a safe place for those negative aspects to come out."

One thing that Saltsman said always ruins coziness for her was what she referred to as "design dishonesty." She described this as the idea that you would use a plot point or character for shock value, or to intentionally manipulate someone's emotional state, such as creating a story beat with the specific intention of making the player cry. As an example, Saltsman described a scrapped design decision for Overland to "gamify" mental health states like fear and anxiety, causing characters not to obey player commands due to being afraid of monsters.

"As you played it, it was so dishonest and gross that we were like, 'This is awful. This is taking away from the experience we want our players to have.' It pulled you out of the moment of protecting people. You're a system now; you're not telling yourself the story."

"I feel better about myself when I have made art that I think reflects my values"

Tanya Short

Short also mentioned the challenge of designing reward systems in her cozy games. While small rewards are fine, she said, over-gamification of behaviors will lead to people participating for points, rather than the intimate feelings associated with simply doing kind actions. She said this is especially true in multiplayer games.

"If you go into World of Warcraft and a bunch of people are dancing in the tavern, that's a little moment where you're really interacting with people as people, because no quest is telling them to do that. But if I were to be rewarded in World of Warcraft and get experience points every time I danced, suddenly that's not a personal expression anymore - now it means points. And any time I'm adding points to doing something, I have to be very careful that it doesn't ruin the original self-expressive, creative, or social use of that feature or moment."

Every panelist at some point indicated that games with coziness and kindness in them were not only something they personally wanted to see, but were something the world needed more of.

"I think we need more kindness in the world," Short said. "It's not commercial suicide. If anything, it's a commercial advantage when you're trying to stand out in the current landscape. Given that it's an option, I feel myself gravitating more toward things that promote pro-social behaviors, things that help people maybe heal from trauma and things that help people relax.

"I feel better about myself when I have made art that I think reflects my values, and one of my values is that I want more people to be comfortable, and I want people to figure out how to be their best self. If my games can help them do that, then that's wonderful."

Disclosure: PAX organizer ReedPOP is the parent company of GamesIndustry.biz.