Brenda Romero's plea for unity among game developers

From Phil Fish and Peter Molyneux to the rift between core and casual, Brenda Romero spoke out against the divisions between us

Brenda Romero's talk about "indie security" ultimately became an impassioned plea for unity within the games industry. Drawing from a career spanning 35 years, Romero took aim at the way developers create divisions within their number, telling the crowd at Digital Dragons, "I want to assure you that it wasn't always this way."

Romero first started in the industry in the early Eighties, and her career since then has encompassed PC, console, social and tabletop games. However, despite her proven skill and experience, Sony's unveiling of the PlayStation 4 in 2013 awoke a nagging feeling of self-doubt. "I felt like all the cool kids were there," she said. "While listening to Mark Cerny talk, I had one overwhelming thought... Why aren't I there?

The train of self-critical thought that followed led Romero to a conclusion that "bothered" her: "I was no longer relevant, because I wasn't making console games... I was no longer core. I felt somehow that I was a loser, because I wasn't [at the PlayStation 4 event] and my game wasn't featured there."

"I want to assure you that it wasn't always this way. There was a time when we found home and were excited to have one another"

As she ruminated on this, the specific term "real game" surfaced again and again. "What does that even mean?" she said, relaying her inner monologue to the audience. "But I'd still catch myself saying it, and what I really meant was that I wasn't working on something that was considered AAA."

At that point in time, Romero's work was not found on PlayStation. It wasn't found on Xbox, or mobile, or through a virtual reality headset, either. In 2008 she had started work on a series of tabletop games known collectively as The Mechanic is the Message; each of them bold and progressive in some sense, each one a unique object not available commercially.

The most famous of these, Train, is implicitly about the Holocaust, asking players to move faceless pieces between train carriages, all resting on a shattered pane of glass. Another, One Falls for Each of Us, explores the Native American genocide; it has 50,000 individual pieces, of which Romero has already made 37,000 (she'll finish them this summer).

The games that comprise The Mechanic is the Message are fascinating and vital by any measure, but Romero admitted that "making this kind of stuff, I felt way on the outside," and that "ultimately, I think that feeling is shared by anyone making games outside the core space." The same was true of the years she spent creating Facebook games; after nearly 30 years as a designer, it was the first opportunity to make something for her own demographic - it felt good to finally do so, but the same sense of isolation was still present.

"If you're making games like these," she said, "it really feels like you're on the outside."

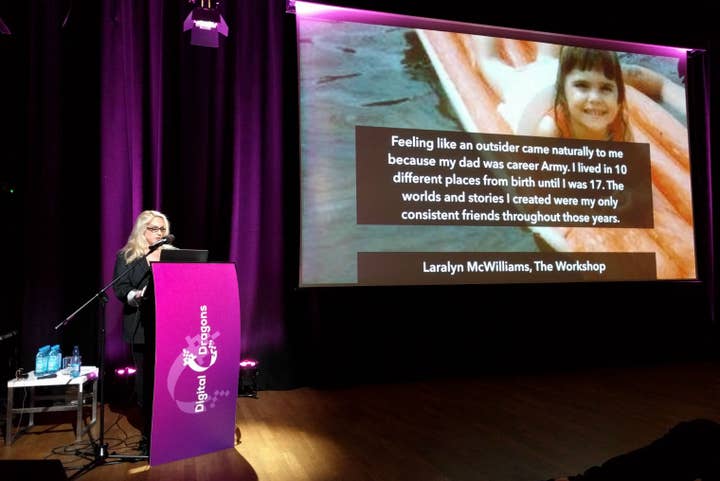

And yet feeling like an outsider is common among game designers. When Romero started in the industry it was the end of period in which her interests had made her feel remote from her peer group. The games industry "felt like home," just as it had to a number of fellow game designers with whom she discussed her response to the PS4 launch event. Romero showed quotes from industry figures like David Goldfarb, Laralyn McWilliams and John Romero, her husband, all of whom spoke of feeling excluded because of "the calling" to make games as programmers or designers, or turning to games as a refuge from unhappy childhoods.

"You'd think that this group of bullied, unique outsiders would finally feel like we're all home, and they'd be sympathetic and welcoming to people," she said, referring to the industry as a whole. "But no sooner did we find our home than we began to divide it up again."

The Game Developers Conference, Romero pointed out, used to be known as the "Computer Game Developers Conference," and there was resistance to console developers when they started to speak and attend en masse. The same dynamic plays out today between console and mobile, between casual and core, between free-to-play and premium, and between publishers and indies. "Someone actually told me 'You're not indie,'" she said with mock fury. "Fuck off! I make games on my kitchen table with my bare fucking hands. How much more indie do you need to be?"

"Someone actually told me, 'You're not indie.' Fuck off! I make games on my kitchen table with my bare fucking hands"

These divisions are "everywhere" in the games industry, representing the "splintering of our community" from within. "Instead of one we are many," Romero added. "I'd say that in some sectors it feels like war, particularly over the last few years."

This isn't limited to those working on a platform with no 'real games', or with a business model perceived to be less worthy or creative. It can also happen to designers whose reputations should be beyond dispute, and whose successes should invite admiration. Romero pointed out that success can be defined in many ways - not just commercially - but she is often "tremendously surprised" by the reaction to people "who do amazingly well."

"We watch their games enjoy critical success, then we begin to trash their future efforts, and what happens is that some of them leave games," she said, offering Phil Fish, the creator of Fez, as an example of someone who "made some beautiful fucking work" but ultimately walked away from development. "What did we lose there?" Romero asked the crowd. Similarly, Dong Nguyen distanced himself from the industry following the clamour around Flappy Bird. In both cases, the negativity came from within the industry, and not just from the public.

One figure received particular attention: Peter Molyneux, whose corresponding slide showed not just a picture of his face, but the phrases Google predicted when Romero searched for the image. "This guy created a fucking genre. This guy is an amazing game developer," she said, before asking the crowd, "How many people have made over 30 games? How many people have made over 20 games?"

Romero asked Vlambeer's Rami Ismail, who was watching rapt in the audience, whether he'd ever made a bad game, to which the response was an immediate, chuckling affirmation. She then reminded the crowd that John Romero, also in the crowd, had made Daikatana, eliciting peals of raucous, knowing laughter.

"Take any game developer that's made over 30 games and you can point at some that failed," she continued. "I made Playboy: The Mansion; I didn't do a good job, it wasn't a good game, and it wasn't me inventing a new genre. But Peter Molyneux did invent a new genre, and nonetheless he takes shit. Why? Because he fucked up one game? You'd hope that we could support him.

"I'm with Will Wright, who said he learned more from his failures than he did from his successes. The problem is that our wisest and our best become black holes, and they keep to themselves." Romero offered her definition of "black holes" as "extremely successful developers, keepers of knowledge that should be shared, but who keep to themselves or only hang out with other black holes, because to do otherwise is to invite unhappiness."

"Peter Molyneux invented a new genre, and nonetheless he takes shit. Why? Because he fucked up one game? You'd hope we could support him"

"I want to assure you that it wasn't always this way," she added. "There was a time when we found home and were excited to have one another."

In exploring these divisions with her friends and peers, however, Romero noticed another trend, one running counter to those arbitrary rifts. Many of the people she talked to - who she initially perceived as being 'inside' - viewed her position as equally desirable. To these AAA console developers, Romero said, she was "living the dream," and following inspiration wherever it led. They missed acting on the kind of "crazy ideas" that publishers would never greenlight. They missed working on an entire game rather than one small piece of something much larger.

Most of all, they wanted to satisfy the desire to "make something different," and that desire is now prompting some of those insiders to head outside. Romero offered That Dragon, Cancer and Her Story as examples of "beautiful" and "different" games created by former insiders. "Not only do we feel the need to make something different, I think we really do need something different," she said. "We need more voices and more perspectives in games."

And, little by little, games like Her Story and That Dragon, Cancer are making those divisions disappear. As a judge on several awards juries, Romero said it has been "just beautifully heartening to me" to see those games share categories and stages with products made by "teams in the thousands, or at least in the hundreds. There was a time when we wouldn't have been able to compete... People aren't talking about polygons or how it looks or how fast it runs, but instead the beauty of the game design.

"So, sure, I might be outside and my friends might be inside... But I've changed this, and I now feel like I'm inside of games and pushing at the boundaries of where they can go. Even if I'm way out there, I'm learning, and there are many games beyond that I haven't thought of yet.

"Ultimately, that's where I want to be."

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner of Digital Dragons. Our hotel and travel costs were provided by the organiser.