"Be ruthless with your own ideas" - Bossa

CEO Henrique Olifiers reveals what lessons developers should--and shouldn't--take from the I Am Bread studio's success

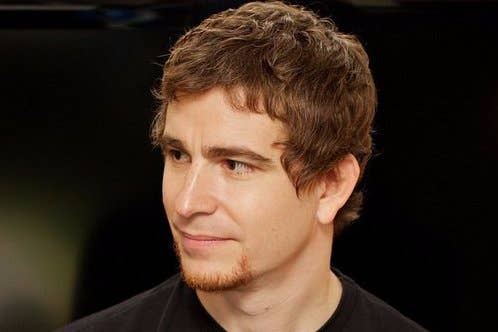

The Bossa Studios of today is a far cry from the one CEO Henrique Olifiers co-founded five years ago. These days the company is best known as the developer of PC hits like Surgeon Simulator and I Am Bread, a company looking to breathe new life into the MMO genre with the ambitious Worlds Adrift. The studio as originally envisioned was a creator of Facebook games looking to expand the platform's domain from casual titles to more midcore audiences.

"At the time, we had the assumption that Facebook would evolve into a very good network gaming platform," Olifiers told GamesIndustry.biz last week. "You have all your friends there, and it was frictionless. You could just put a game in there; you didn't need specific hardware to play, and the games were evolving pretty fast, so we assumed that would carry on. Unfortunately, that's not how it transpired."

Bossa produced a pair of well-received Facebook games--Monstermind won a BAFTA award in 2012 for Best Online Browser Game, while Merlin: The Game was nominated in the same category the following year--but they weren't commercially successful enough to keep the studio from needing to hit the reset button. Olifiers said it was a painful switch to make, given the company had already invested so much into its original vision.

"'We should go midcore now because the casual market is too crowded' is an approach you only take when you're not up to the fight of making the best game possible in class and get it out."

"We had a skillset that was geared to making games on Facebook," Olifiers said. "It was about server-side structure and making sure that real-time multiplayer games could be done in Flash, which not many people had tried at that time. So the skillset internally was very compatible with that vision. And also trying something on an entirely new platform, all those relationships had to be built. We didn't know anyone at Steam or Valve, we didn't know anyone at Apple, and so on."

While the logistical and technical problems of switching platforms were substantial, Olifiers said the move didn't impact the end goal of the studio, or even require a different set of core competencies.

"The idea was to make games that are very different and special on the platforms where gamers can enjoy them with their friends. That was what we stood for," Olifiers said, adding, "If Steam stopped working tomorrow--knock on wood, because that would be a tragedy for all of us--I'm pretty sure we'd be able to switch in the same way it did before, exactly because we started this studio with this very agnostic approach as to which platform we were. We decided to do Facebook right then because we had a vision for it. It didn't materialize, but we were never bound to a specific platform from our mindset."

That approach is evident in Bossa's development slate. While the company found success on the PC, it is working on games for smart watches and Valve's Vive VR headset, and has also brought Surgeon Simulator to mobile platforms, PlayStation 4, and even added Oculus Rift VR support.

Bossa's original strategy of bringing more traditional gaming experiences to a platform largely defined by casual titles has parallels in the recent flood of developers targeting the midcore market on mobile platforms. But Olifiers said developers pursuing that strategy should make sure they're doing it for the right reason.

"The change in the market of people saying, 'We should go midcore now because the casual market is too crowded' is an approach you only take when you're not up to the fight of making the best game possible in class and get it out," Olifiers said. "If you have the best game in a class, it doesn't matter where you operate, you're going to be successful. Now that's a very big ask. It's a very tough proposition, and everybody fails at that. But there's a difference between people who set their target at making the best possible [game] and the people who want to do things that will be successful no matter what because they think they understand the market in one particular way. I see those people needing to move from different markets in order to exploit those opportunities. But that's not what we stand for. We don't look at a market and say, 'This is too crowded, we shouldn't go there.' If we have a game idea we think is great, it doesn't matter which market it goes in, it's going to succeed, right?

"There's a lot of good stuff around and you have to be as good as, or better than, that. But that should never be a deterrent for anyone trying to start."

"It's not as easy for you to cut through the noise and get the game seen today as it was back then in 2010 because the bar has been raised," Olifiers added. "There's a lot of good stuff around and you have to be as good as, or better than, that. But that should never be a deterrent for anyone trying to start. You cannot start a company and be honest with yourself that you're going to succeed if you think, 'My game's not going to be as good as or better than the stuff out there.' You have to bring out a better product or a better idea to have the right to do it, I think. If you're doing something worse than what already exists, you have to stop, look at it, and ask why you're trying to do this. What am I adding to the world? What am I giving to the players?"

If the answers to those questions are "Not much," it might be helpful to keep another piece of Olifiers' advice in mind: "Fail fast." He's a big advocate of failing fast and knowing when to walk away from a game that isn't going anywhere.

"Be ruthless with your own ideas," Olifiers said. "They come, they go, you forget about something. Sometimes you have an idea in the pub when you're having a drink and the next day you don't even remember it. Did you lose something? No. So think about that when you're conceiving a game. If it doesn't work, make sure you find out it doesn't work very fast, either by asking other people to play it early or discussing it with them and getting some feedback. Don't latch on to ideas that don't seem to have traction."

One common way Olifier sees that attachment manifest itself is when developers run an unsuccessful Kickstarter campaign for their games, but carry on with development undaunted.

"I wish I had a black box where I would just put in an idea and the other end just came out with a yes or no, and that told me to stop and go on to something else," Olifiers said. "But some people don't see it like that. Some people say, 'My Kickstarter failed. People don't understand what I'm trying to do. I'll keep at it.' No, you gave it a shot and people didn't accept it. The best thing you can do is drop it and start something new."

It's a lesson Olifiers said Bossa has tried to embody throughout its life. He estimates the studio has produced as many as 80 playable prototypes through in-house game jams that sounded great on paper, but were killed when they didn't work nearly as well in practice. Another lesson he thinks developers could take from Bossa's success is to respect their communities.

"Some people say, 'My Kickstarter failed. People don't understand what I'm trying to do. I'll keep at it.' No, you gave it a shot and people didn't accept it. The best thing you can do is drop it and start something new."

"Listen to them," Olifiers said. "This is what we're trying to reinvent ourselves for now with Worlds Adrift. It's not to leave the players to tell you what to do. We still have authorship, we still have creative control. But test your ideas with the players, listen to their concerns, listen to them try to tell you what they like, and what they don't like. That's so valuable when you take it to heart. You'll get the odd one out that doesn't understand and wants to give you a hard time just because that's how they like living their life, but in the end, the net result of listening to your players is so positive. There's no better way to develop a game than in conjunction with your players, by listening to what things matter to them. I have never seen a game fail because they listened too much to their players. Maybe there is one, but I can't name it from the top of my head."

As for lessons Olifiers believes people absolutely shouldn't pull from Bossa's success, the primary one is still "Don't design games for YouTube." Beyond that, he worries people might see the studio's early adoption of different technologies and emulate it carelessly.

"We do these things in a very calculated way, a very conservative way, in a way that doesn't risk the future of the studio," Olifiers said. "For interesting new technologies, be smart about how you go around these technologies. Don't listen to what third parties give you as answers at face value."

He pointed to the studio's experience with VR as an example. After becoming convinced that the current wave of VR technology was going to be a legitimate market for the industry, Bossa tested out the tech with a VR version of Surgeon Simulator and gauged the reaction it received. That was about two years ago, and it prompted the company to begin hosting VR developer meet-ups at the studio every two months or so.

"In the past two years, we have been learning about VR more than anyone else without actually spending that much on VR," Olifiers said. "And this has put us in a position that when VR is big, and it's going to be big, we are ready for it without having risked the future of the studio on a project that we would now have in our hands without having anywhere to launch it... You can be very excited about new technologies and new platforms, but be very wary of what they represent from a commercial point of view and find clever ways of being there when it happens without betting your house on it."