The BBC Micro's macro impact

Why I Love: The Oliver Twins recall the computer that inspired a generation and cemented the UK's status as an early hub of game development

Why I Love is a series of guest editorials on GamesIndustry.biz intended to showcase the ways in which game developers appreciate each other's work. This installment was contributed by Philip and Andrew Oliver, creators of Dizzy and co-founders of Blitz Games and Radiant Wolrds.

It was 1980 when the British Broadcasting Corporation had a dream to educate a nation to what they believed was a coming of the computer revolution.

They signed a contract with Cambridge-based Acorn Computers in early '81 and by December the BBC Micro Model A went on sale, followed quickly by the Model B with 32k of RAM priced at £399. Today that would be £1,400 so it wasn't cheap, and for two teenagers that meant a LOT of pocket money, household chores, and rolling together several birthdays and Christmas monies together to get close, but we were determined and finally got our BBC Micro Model B in December 1983.

Housed in a beige plastic case, with a full-size, professional keyboard, it contained a 6502A CPU running at 2 MHz, it had 32KB of RAM, 32KB ROM which contained the operating system and BBC Basic. The display was memory-mapped with eight graphic modes ranging from 640x256 pixels in mono to the popular Mode 2, which had 160x256 pixels in eight colours. But these did eat up 20KB of the RAM, leaving only 12KB for the games or other applications. There was also the Teletext, character mapped, graphic mode which was fast and took only 1KB of the RAM.

Whilst marketed as an educational machine, its true appeal to us and most kids at the time was the amazing arcade games it ran, mostly coming from Acornsoft, although the BBC name and Acorn's marketing did help convince parents that it wasn't just a games machine!

The early batch of games set a new high for gaming at home with many inspired by arcade classics. There was Snapper (Pac-Man), Rocket Raid (Scramble), Planentoids, (Defender), Mr Ee (Mr Do!), Killer Gorilla (Donkey Kong), Zalaga (Galaga) and Thrust (Gravitar).

Acornsoft also produced a number of text adventures which helped inspire our Dizzy game puzzle adventures. We loved the puzzles, but always dreamt of what they'd look like with great graphics.

There were of course some new and original games like Frak!, Repton, StarShip Command and Castle Quest. Each brought fun new gameplay elements and presented them in different ways. As we played each, they were unconsciously loading us with many ideas. It was fun research although we weren't aware of it at the time.

Then came the mind blowing 3D games. We'd seen BattleZone in the arcades, but having 3D games at home seemed inconceivable. First up was flight simulator Aviator followed by Revs and Sentinel by Geoff Crammond. Then the mind-blowing space trading game Elite from David Braben and Ian Bell.

Looking back on it, owning a BBC Micro became a period of heavy research into different game genres. We didn't realise it at the time; we just loved playing games. We bought a Viglen Floppy Disc Drive for the BBC and that opened up the ability to load games really fast (under a minute), but more importantly we were able to borrow compilation discs from a few friends at school. We loved playing all the different games and seeing the variety.

But the great thing about the BBC was its approachable, easy-to-use Basic programming language. When you turned it on, there was a black screen and a cursor for you to start typing. That was fairly common in those days, but then they also had cursor control to allow you to change where you were typing and a text Copy and Paste system. Now these might not sound revolutionary these days, but at the time, this made typing in listings so much easier. On other computers at the time, if there was an error on a line you simply had to retype the full line. Coming from the Dragon 32, we picked up this new Basic very quickly, and were determined to make our own games. This led to our first lucky break...

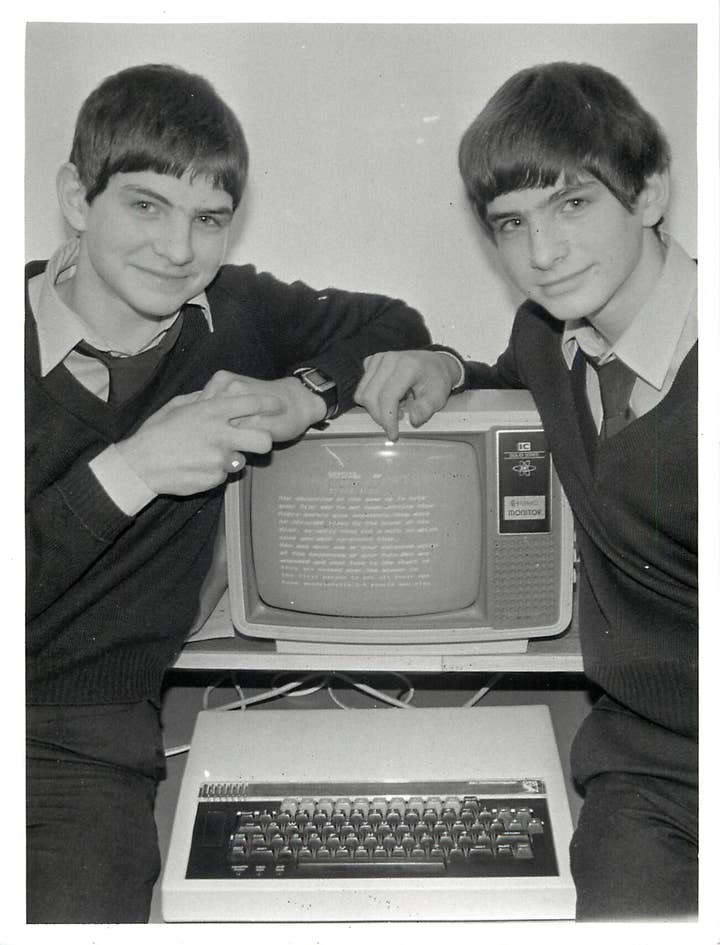

Like most kids in the '80s, we often watched Saturday morning TV programs, which were live three-hour shows in a studio, that introduced articles including pop groups, short programs, and cartoons. One of these, called 'The Saturday Show,' announced a Design a Game Competition, and kids had a month or two to send in their best ideas for a computer game. Having just bought a BBC Model B, we decided that we'd better make a game that wouldn't require much speed since Basic was pretty slow. We came up with the idea to create a logic-based board game and called it Strategy, later released under the name Gambit by Acornsoft.

The competition was sponsored by Commodore and the prize was supposed to be a new Commodore 64, but because we already had a BBC Micro, they decided to award us a Commodore Monitor instead, and we were given our prize live on ITV!

The game was eventually released by Acornsoft, but we didn't hang about. With the success of Gambit we wrote lots more small Basic games and sent them to publishers. Sadly, most never replied, and those that did weren't too interested in games written in Basic, and that wasn't too surprising when we looked at the quality of the games others were writing in assembler, often referred to as 'machine code'. That was some kind of voodoo magic that we had no hope of understanding - especially as we didn't want to spend money on books!

We eventually found an outlet for our games through a 'magazine on cassette' called Model B Computing, which would pay us £50 for a game, and £25 for a game review, plus the game!

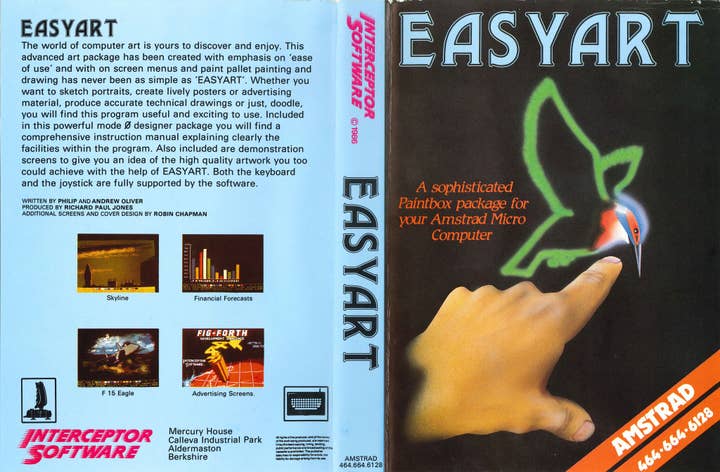

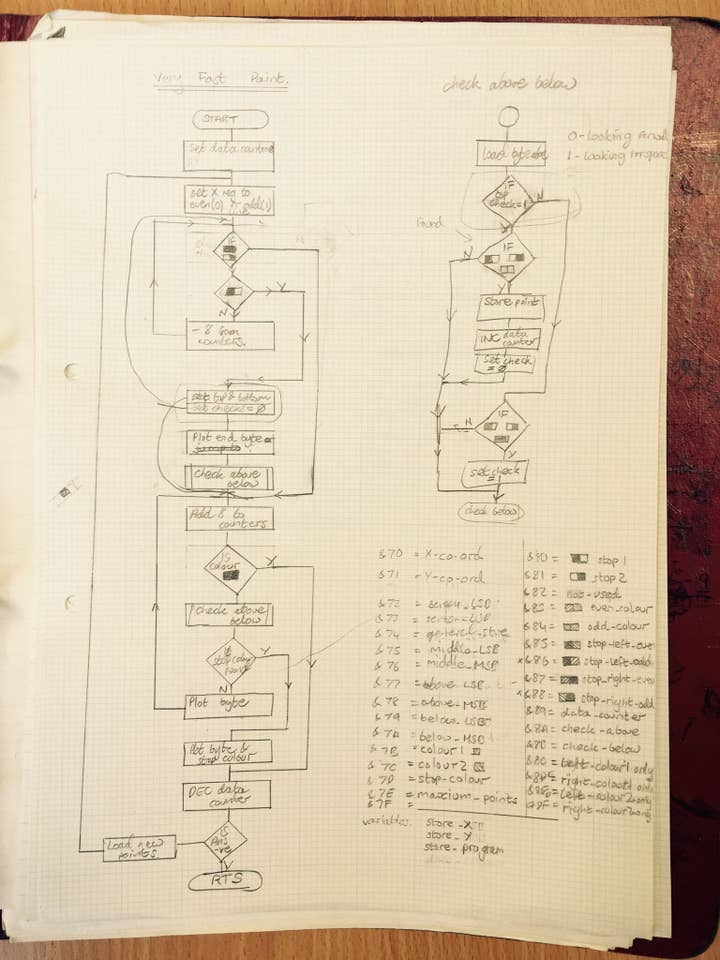

We were 16 and studying for our 'O' Levels when we decided we really needed to learn assembler. We desperately wanted to make arcade games, and the BBC's built in assembler led to our next big break. We wrote an art package in Basic called Easy Art to sell as a utility for budding computer artists. It utilised some of the built-in commands like 'line', 'draw' and 'polygon fill'... but we also wanted a 'paint' command that would flood-fill an area. We worked out the recursive style algorithm in Basic and ran it... but it was SO slow, and would often leak if the area wasn't completely closed. When we say 'slow', we mean half-an-hour-slow for large areas, or a leak!

We spoke to our teacher of Computer Studies, who up to that point hadn't attempted to teach us anything we didn't already know. But he offered to translate just the Basic code for the paint into 6502 assembly language and quickly showed how this could plug into the Basic. Incredible that you could write in-line assembler in the Basic, a very powerful and useful feature. He hand-wrote the instructions over a weekend and we typed it all in. After a week or so of de-bugging we eventually got it running learning 6502 assembler as we deciphered his almost illegible handwriting; this gave a 10-20 times increase in speed.

Easy Art moved us up to the next level. We could now write assembler and it was time to write an arcade game. 'O' Levels complete and a long summer holiday ahead of us, we decided to create Cavey, a prehistoric take on Galaxians with a Caveman shooting Pterodactyls. Acornsoft agreed to publish this but sadly never did, whilst Firebird paid us £2,000 for Easy Art and wanted more from us. Having now produced a game with fast sprites, we felt there was an opportunity to develop a utility called Sprites Plus to enable hobby programmers to write arcade style games with fast sprites in Basic, with a sprite editing system. Sadly Firebird pulled out of publishing BBC Micro software but Sprites Plus, renamed to Panda Sprites and Easy Art were published by Interceptor Software.

Whilst it wasn't a massive success in itself, the tools allowed us to start producing our own games very quickly.

Over the next few years we wrote over 30 games, had 26 UK No. 1 best sellers and sold over five million units, although ironically these were on the Amstrad and Spectrum as publishers favoured these platforms over the BBC, which had low software sales and almost all through exclusive publisher Acornsoft.

The legacy of the BBC Micro

The BBC Micro contributed more to inspiring and educating a generation than any of those involved could have dreamt of. Acorn anticipated the total sales of 12,000 units, but eventually sold more than 1.5 million. 80% of UK schools had BBC Micros and most were used for over 10 years.

Sophie Wilson, responsible for a lot of the architecture and BBC BASIC, went on to design the ARM RISC processor which was a massive breakthrough in speed and power consumption and is fundamental to the power of all smart mobile devices. Many leading professional IT and software engineers learnt their skills on the BBC Micro and the games industry is full of BBC Micro-taught students and evangelists.

Thank you BBC & Acorn Computers for a computer that inspired a generation and helped put the UK at the front of the computer revolution!

If you enjoyed this brief and nostalgic overview of the BBC Micro by the Oliver Twins - there's a whole book of the Oliver Twins story, from the early 80's to setting up Blitz Games. Published by Fusion Retro Books.

Upcoming Why I Love columns:

- Tuesday, October 24 - Yooka-Laylee's Gavin Price on Super Mario Kart

- Tuesday, November 7 - Wasteland 3's Brian Fargo on Inside

- Tuesday, November 21 - Voyageur's Bruno Dias on Magic: The Gathering

- Tuesday, December 5 - Lightseekers' Ana Steiner on World of Warcraft

Developers interested in contributing their own Why I Love column are encouraged to reach out to us at news@gamesindustry.biz.