How to get a job as a games writer

The GamesIndustry.biz Academy looks into how to get a job writing video games

Finding a job in the games industry is no easy task. Our guides can help you to find the right path to the games industry job of your dreams. You can read our other in-depth guides on how to get a job in the games industry on this page, covering various areas of expertise.

After 68 years of recognising excellence in science-fiction and fantasy literature, the Hugo Awards added a video game category to the 2021 edition.

While the accolade will only be offered this year and has yet to be added permanently to the organisation's roster, it still represents a great step towards the recognition of interactive storytelling.

With each year passing, the games industry becomes more interested in story. While the big blockbusters are still typically gameplay-focused -- as shown by the best-selling games in the US in 2020 -- there's a growing trend towards trying to push the boundaries of narrative in AAA games.

"One of my favourite writers told me that she runs to have something she hates more than writing"

Olivia Wood

Even developers who have historically been purely focused on gameplay have experimented with narrative elements, such as EA venturing into story modes in recent FIFA titles, or NBA 2K making the narrative MyCareer Mode a core feature of the series.

Pushed by an indie scene that's always at the avant-garde of storytelling, AAA has a new appetite for carefully crafted stories, which have shined in recent years with titles such as God of War, The Witcher 3, Persona 5 or The Last of Us Part II.

This shift, which contributes to making interactive storytelling more visible, might motivate an entire new generation towards games writing as a job. But before opting for such a career, you need to make sure you're getting into it for the right reasons. Like most artistic jobs, it's easy to idealise games writing.

Much like game artists don't just draw what they want all day and game journalists are not paid to play video games, writing games doesn't mean writing compelling stories day in, day out. So be aware of the caveats, says Olivia Wood. She's a narrative designer, writer and content manager at Failbetter Games, and also works as a freelancer as part of Bear Wolf -- she was one of the writers on the indie anthology game Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, among others.

"Writing is hard," she says. "It will sometimes make you miserable. Just because it does, doesn't mean you suck. One of my favourite writers told me that she runs to have something she hates more than writing. Although if you hate it too much, do something else. Life is too short. It's not a good way to have your name remembered in the annals of history. It's also not the best paid job in the industry, and it's very competitive."

There are a lot of jobs you can put under the games writing label. Narrative designers and writers are typically the most common ones you'll encounter.

"As a writer, the entirety of your job is based around writing and solving problems related to writing," says Xalavier Nelson Jr., narrative designer and writer of Hypnospace Outlaw and Skate Bird, and creator of An Airport for Aliens Currently Run by Dogs and the recently announced Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator.

"So if you are a game's writer, it is feasible that you could spend your entire tenure at a studio writing screenplay and format scripts. Narrative design, alongside also doing writing, usually involves looking at the mechanical basis of the game and visual aspects, and collaborating with a team to determine ways to convey your narrative through other elements that are not solely narrative components."

What education do I need to get a job in games writing?

Some of the most memorable stories told in games have been written by creators with an educational background that has little to do with storytelling. Uncharted creator Amy Hennig studied film theory and production. Mass Effect lead writer Drew Karpyshyn has a BA in fine arts. Metal Gear creator Hideo Kojima studied economics.

Your degree isn't what's going to make you a game writer. But that's not to say you shouldn't study for one.

"I hold a bachelors in English: Creative Writing Emphasis, Theater minor," says Lauren Stone, Clancy IP writer at Ubisoft Reflections. "I don't believe a specific degree in writing is necessary to become a games writer, however, big caveat, it makes it much easier to get a work visa as a 'skilled worker' in a foreign country.

"Because games are global, and you sometimes have to chase the projects and jobs, being able to get a visa to work in another country could be necessary to advance your career. If you want to be a full-time staff writer for a major studio, then having a bachelor's degree can make that pursuit easier, especially before you have a substantial body of work that you can use to support your visa application to immigration boards."

Wood agrees with Stone on the visa front, but insists that it's not necessarily a writing degree that you need.

"I do think that enough of an education that you understand grammar rules is useful -- so that you can pick and choose when to ignore 'correct' style, fight the right battles, and not be intimidated by pedants," she explains. "A formal education can also introduce you to subjects that you wouldn't have sought out of your own volition, expose you to writing that you might not otherwise have got around to.

"A degree can provide you with the opportunity to develop your skills in criticism. I think history degrees can be incredibly useful -- I'm envious of some of the rich layers of history that my colleagues know exist to draw from. At the same time, I have no regrets about studying philosophy and politics -- that gave me different advantages. But all this is stuff you can do on your own time, and don't need to be formally guided into. While not a games writer, Terry Pratchett, one of the best and most compassionate writers we've had, didn't go to university."

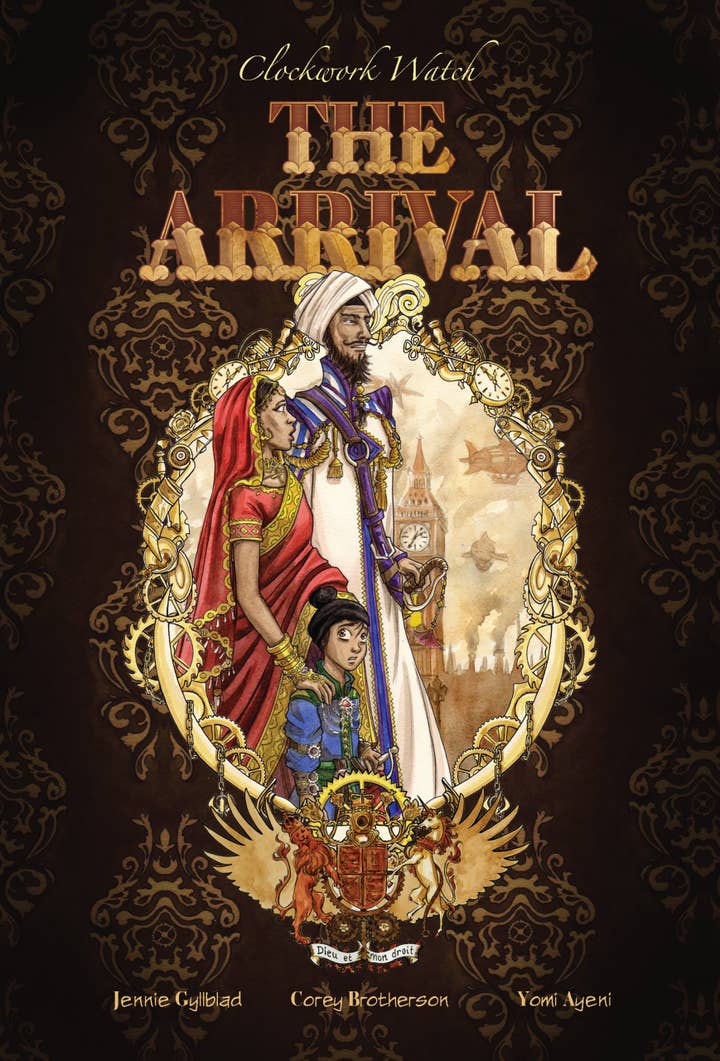

Corey Brotherson, comic book writer and lead narrative designer at Silver Rain Games, spent most of his 20-year career in the industry as a journalist, as well as a content producer and writer for PlayStation Europe, for over 12 years. He has a BA in English language and literature, as well as a master's in journalism.

"I thought if I got a degree in English language and literature, then I've got a foundation for fiction, which is something I wanted to do but I had no idea how to get into. I was trying to think long term: I don't know if you need a degree to become a fiction writer, but hopefully that will help. Both degrees actually became really important in being able to create this foundation for games writing. Mainly in terms of organisational writing, communication and creativity -- there's a lot of transposable skills from journalism, to games writing, to marketing. They have helped in terms of being able to let employers know that I was serious about becoming a writer and that I had enough grounding there."

Kike Ayoola, writer at The Wagadu Chronicles developer Twin Drums, has a BSc in computer science. She explains that a formal education in game design can also be very beneficial to being a good games writer.

"You're writing for games with mechanics and so many other design elements that you need to integrate your narrative with; I think having a good understanding of all of the parts that bring games together could be a huge advantage," she says.

The degree you choose to pursue can also be linked to the genre of games you want to work with, or the type of stories you want to write.

"Don't forget that we have all kinds of writers in AAA," Stone says, adding that many programs could be beneficial depending on the game being made. "If you're working on a Clancy game [and] you have a degree in Criminal Justice or Political Science you may be more appealing than someone with a degree in English because you bring specific expertise to the table. Being able to highlight what makes you unique and targeting projects and teams that will see the value in your knowledge is more important than ticking the box for 'has a degree'."

"The ideal education for a writer is something that makes you as broad of a person as possible"

Xalavier Nelson Jr.

When he's in a position to recommend or hire writers, Nelson says he doesn't care where or how they trained -- what matters is their technical skill as well as the perspective they bring to their worlds.

"The ideal education for a narrative designer or writer in my opinion is something that makes you as broad of a person as possible. The more resources you can pull from in terms of mythology, strange technical minutia and trivia, little pieces of how other mediums have solved problems, history, and philosophy, the better equipped you'll be able to not just solve problems with your teams, but to write richer stories coming right out of the gate. Any education, whether it's formal or not, that provides you with that full broad scope of being human, is the way to go in my opinion."

What do I need to get noticed as a games writer?

- Build a portfolio of writing samples

As made abundantly clear by the variety of educational options available to aspiring game writers, there is no one path into the job. But there are essential elements that you need to perfect, and most of them revolve around your writing portfolio and what should be in it. It is your most precious ally, and ideally it should be composed of work that is relevant to games.

"This includes things like writing samples that show off your ability to write dialogue [and] an understanding of barks [short lines of ambient dialog]," says lead narrative designer at Capy Games, Kaitlin Tremblay.

It's all about showcasing that you can write for games specifically, so you should display "a focus on dialogue and cinematic scene construction, as well as an understanding of the different types of writing and narrative structures used in games," she continues. That includes choice writing, branching stories, open-world and combat barks, item descriptions and flavour text, tutorials, linear versus non-linear narrative, authored content versus systemic behaviours, and more.

However, it's worth noting that any writing is better than no writing at all. "If you want to be a writer, write," Stone says, before noting that she's honed her craft as a writer in other media before transitioning to games. She adds that she knows plenty of novelists and screenwriters who have transitioned because they created a body of work. What matters is that you have done writing before applying for jobs.

"You can't apply somewhere, even as a junior, and expect to start writing there," Wood adds. "While junior writers should be taught and given room to expand, not all companies will be great at this, and writing jobs are so popular that you need to have samples to show genuine interest in the role, and that you can actually write. So, while there's lots of advice telling you 'don't work for free' -- which is largely true -- it should probably be 'don't work for others for free.' To get into game writing you need to have written."

- Finish and publish stories

Writing for yourself so you have writing samples to show is sometimes still not quite enough though -- you ideally need to actually finish and seek publication of your work.

"There's a lot of people in all creative industries that said to me: if you can finish a story, then that shows at least you're dedicated to the craft itself," Brotherson says, noting that he had roughly a dozen stories under his belt when he was approached about working on indie project Windrush Tales and (separately) working at Silver Rain Games.

"And that probably gave [me] the confidence to be able to say: [I] know how to create a plot, how to finesse a story, how to create compelling characters, how to write dialogue. Those things were just as important as me being able to say: I've got a MA and I've got a BA. That will give you a substantial advantage when you're applying for jobs."

Wood recommends regularly writing flash fiction and sending it to any company that might publish it. If you can't show your work to other people and listen to feedback, you're never going to learn or improve. She warns that this can be a bruising education -- but it is all necessary.

"In games writing you are going to have work cut, changed, rewritten by someone else, thrown out," she explains. "Getting used to rejection, trying to learn not to take it personally or to heart... is pretty vital. I'd look at competitions, at game jams, and use them as motivation for the creation of portfolio pieces. There are loads of talks on writing online; many GDC talks are on YouTube. Watch them. Build a portfolio, apply for jobs, politely ask for feedback and be gracious when you get rejections."

- Make playable content

Your portfolio should also demonstrate an understanding of the tools of the craft, and showcase playable content.

"Try as much as possible to familiarise yourself with the variety of game writing software available and try as soon as possible to start making games," Ayoola says. "Even making small practice games on your own shows your enthusiasm and dedication to the art, and helps you as a game writer to begin to understand the structure of your stories and how to use your narrative to drive it forward."

Twine was overwhelmingly mentioned by our interviewees as an essential piece of software for aspiring games writers to get accustomed to. Nelson points out that he "got the work by doing the work" and he started with Twine because that's what he "could wrap [his] head around." And the more he practiced it, the better he became at it, allowing him to embrace story and game development as a whole.

"[I saw] my initial lack of knowledge not as a limitation but as a constraint that I could do interesting creativity within," he explains. "What I could pull off technically gave me an avenue through which to view the game development process as a whole, and later on really benefit my clients when it came to building narrative structures and designs that specifically took advantage of solutions that would make the game easier to build, as opposed to trying to cellophane wrap a story over a shape that really did not want it."

Tremblay adds that making a game in Twine really teaches you fundamentals of choice design, branching narrative, and how to use variables to tell a player-driven story.

"You can include barks and you can show off snappy dialogue in a Twine," she continues. "While not all studios make branching narratives, a released game made in something like Twine is still valuable because it's a released game, and there is so much you learn about scoping, balancing work for a release date, and so on, from developing and releasing a game, no matter the size or engine it is made in. Whatever engine or software you want to use, know what you want to get out of it, formalise your learnings from it, and treat it as what it is: a released game in your portfolio that people can play and that you can use to build your reputation, experience, and skills."

- Play the networking game

Finally, networking is absolutely key to getting noticed as a games writer. Doing all of the above will be almost worthless if you don't take the time to put yourself in the spotlight and interact with peers.

"Junior games writing jobs are notoriously hard to come by, but that doesn't mean they don't exist," Tremblay says. "Building genuine relationships with other game writers and developers is an important way to gain connections to people who are looking and hiring. A lot of people want to be games writers, so the competition is tough, and landing a gig often relies on words of recommendations and people being suggested to fulfill roles.

"So genuinely participating in the games writing community through events, on Twitter, is one way of building your network and letting people know you're looking for a job. But remember not to treat people like conduits to a job; treat people like people, build earnest friendships, and grow your network and community through shared interests, enthusiasm, and support."

Brotherson says networking played a fundamental part in a good portion of his career, whether that's in games or comic books. So it's worth being persistent even if that's not your thing.

"[Networking] does have this wonderful trickle down effect -- and I wouldn't necessarily say that I'm a particularly good networker," he laughs. "I'm quite introverted, I tend to be quite nervous and anxious in large crowds. But I think that combination of putting yourself out there, being open to talking to people and being open to opportunities that come up [is fundamental]."

What qualities and skills do I need to work in games writing?

Before getting into the essential skills needed to be a good games writer, it's important to understand that different studios will have different needs and requirements.

"A lot of AAA studios rely heavily on barks, so demonstrating a thorough understanding of the role of barks, and how to write barks well, is important," Tremblay explains. "Other studios, especially mobile, focus a lot on dialogue choice and branching narrative, so being able to demonstrate a scalable understanding of how to develop meaningful branches that don't blow up scope, and how to write dialogue choices for expressive player agency, are important experiences there. Some studios have all their dialogue voiced, and others don't. A games writing portfolio isn't one-size-fits-all."

- You need to be a good writer

This is an obvious one but to get a job in games writing, you need to be a good writer -- especially with strong dialogue chops, Tremblay says.

"An eye for detail never goes amiss in writing -- people notice the small but pleasant things in your work"

Kike Ayoola

"'Good writing' is obviously subjective, but a focus on being adaptive, writing strong dialogue, [and] knowing how to balance thematic and gameplay needs in writing are all crucial skills to have. Knowing how to create and develop characters, how to write dialogue, how to write scenes, how to construct plot, and how to use and break structures and conventions is really important since that is the job."

Being a good writer also means being detail-oriented and having enough imagination to turn a setting that is being given to you into a believable story or world.

"[You need] good understanding of the lore you're working with and the ability to build worlds and characters from this," Ayoola says. "I think an eye for detail never goes amiss in writing -- people notice the small but pleasant things that end up in your work."

- You need to learn how story fits in the game-making puzzle

No one will expect you to know game development in and out as a writer, but having a willingness and ability to understand the mechanics and features of the game you are working on will go a long way, Ayoola points out.

Tremblay adds that learning how games are made is about understanding the processes, the difficulties, and the successes.

"Knowing how a game gets made can only ever help you know how to better tell a story for games"

Kaitlin Tremblay

"Understand the role of different disciplines, how they work together, how different engines determine what, and how story gets implemented into a game, since that will determine what you can write and where it can be triggered and surfaced to the player," she says. "Knowing, generally, how a game gets made can only ever help you know how to better tell a story for games. This will also help you respect other job disciplines, their responsibilities, and how you can collaborate with them to tell the best story.

"You're obviously telling the story of the game and providing characterisation, but writing is also often reinforcing gameplay goals, mission directives, abilities. So understand that your writing will likely have to fulfill a few functions, and try to write with all of those goals in mind."

- You need to be collaborative and open

Making games is highly collaborative, and as a writer you will be working with a lot of different departments. So knowing how to work with others and receive feedback is paramount.

"You have to put your ego aside," Brotherson says. "Being able to communicate your ideas and being able to work with people who have their own ideas about what the story should be and what the character should be doing, and being able to convey and work together to make the best story possible, is the only way you can work forward on a game."

"Often we are told to 'kill our darlings' -- in games, you're less of a parent and more of a farmer"

Lauren Stone

Stone explains that it doesn't mean that you shouldn't fight for your work if you really believe in it, but you will have to let some things go.

"Often we are told as writers to 'kill our darlings' -- in games, you're less of a parent and more of a farmer," she says. "You raise chickens for eggs, but eventually you're going to have to kill your old hens that stopped laying. 90% of everything you write will never see the light of day. You can try to use them for soup or coq au vin, but they no longer work as intended. If you're good, that 10% will ship. You have to be diligent, thorough, but not controlling and that is a very delicate line to walk.

"I would highly recommend getting into writing groups or collaborative creation, whether that is game jams or another discipline, like improv or theater. Learning to work with other people and take feedback and realign to support the team is crucial to staying in games."

- You need to be able to work to specs and deadlines

None of your creativity is worth anything if you're not able to deliver it on time or within the guidelines that have been given to you.

"You [can't] complain about writing barks every single day for about a week," Brotherson adds. "[Sometimes] you're writing one bit of dialogue in lots of different ways that are conveying the same message. 'Take cover', 'I'm taking cover', 'okay, I'm getting undercover now'... and you're just basically doing that repeatedly over and over again in an Excel sheet, until you're absolutely sick of trying to find different ways of saying the same thing. This is part of the process and it's part of the job."

"It's all wonderful if you can create glittering characters, but if you can't do it within a deadline, you're going to be nobody's friend"

Corey Brotherson

He adds that he learnt about the primordial importance of working to specs the hard way, after a writing test gone wrong at a AAA studio. While he was praised for his imagination and creativity, he failed a part of the test that asked to write according to specific constraints.

"It's all wonderful if you can create a story and create glittering characters, but if you can't do it within a deadline and you're holding up lots of other departments in the process, you're going to be nobody's friend. Creativity can only take you so far. Being able to stay on spec is super vital. And it sounds obvious, but it's very easy to get caught up in the excitement and the whole: 'Oh my god they've given me X, Y and Z from this game to write about and I'm gonna really show them how amazingly imaginative I can be.'

"You need to sometimes be able to step back and let go of what you're doing and saying: I've done the best I can. Yes, I could reiterate it and work on it, and make it even better, but there are deadlines, there are money situations here that need to be considered. There's wider considerations and consequences. As important as writing is, you are not the centre of the game."

What are the common misconceptions about games writing?

The most common misconception about being a games writer is that everything you do revolves around writing words. But it isn't the case.

"There's a really strong misconception where, as a games writer, you're just sitting there and you're turning out characters, and you're writing dialogue, and you're doing all this really really fun stuff," Brotherson says. "You do get to do that. But before you get to do that, you have to do an absolute ton of structural work. You're having to get around putting ideas down and working through those ideas and rewriting those ideas constantly, and making sure that it works not just from a narrative and storytelling perspective, but from a game's design perspective as well."

You might also not get to write your own ideas, so you need to be able to get excited about writing about other people's concepts.

"You are not the 'author of your own story'. If you want to tell 'your story', write a novel, but a game is a collaborative effort"

Lauren Stone

"You are not the 'author of your own story'," Stone says. "If you want to tell 'your story', write a novel, but a game is a collaborative effort. There will be more stakeholders who get a say in what you're writing and whether or not it ever sees the light of day than you will ever know. Some work you think is completely brilliant other people will hate, and something you think is too much will make it into the trailer for your game. You never know what people will connect with, so treat everything like it is that million-dollar cinematic."

Sometimes a part of the story will need changing because the animation team couldn't get around a technical challenge. Sometimes shareholders will ask the team to cut a character because it performed poorly in a focus test. That is just the reality of game development.

Nelson clarifies that the job of a game's writer is not just to tell a story, but to support whatever the creative team's vision is.

"You are an enabler as a games writer, not a driver, even if the game is a narrative-driven game. The first experience I had in games was discovering just how much the mundane, frustrating, reality of game development had been obfuscated for me as a player. Things that I assumed were trivial, like even putting a dialogue box on the screen, were actually nightmarish processes. So, I think, coming through the door with a great amount of humility and with a desire to learn as much as possible about the other pieces of the project that you will be impacting is essential. Because one line of dialogue you write can mean up to months of work for your collaborators.

"The more you know the costs of your words and your work, the more you can intentionally harness those moments so that if you're spending a lot of money, you're doing it to make something incredible. You're walking into it with your eyes fully wide open to all of the challenges that await you."

Advice for new and aspiring games writers

- Operate from a basis of stability

As touched upon by Olivia Wood, games writing is a labour of love and certainly isn't the best paying job the games industry has to offer. So you may need to have a day job to support your creative endeavours, which is something Nelson is keen to normalise.

"The greatest piece of advice I could give to a games writer as well as anyone else looking to join the game industry is to operate from a basis of stability whenever possible," he says. "A huge plot point in an '80s movie is when someone tells the aspiring creative hero: 'Don't quit your day job kid!' and it's a motivator to prove that sucker wrong, and move towards your dreams and show the world just what you can do.

"As tiring as it is to maintain a day job, it's that much harder to write 50 grenade barks when you haven't eaten today"

Xalavier Nelson Jr.

"And I want to heavily destigmatise the idea of maintaining a day job while writing for games or searching for a career in games, so that you not only have a backup but you have a basis of stability to operate from in terms of pursuing your career.

"Because let me tell you two things. When you make choices, especially important career choices, from a position of desperation, it is very likely you will be making incorrect choices. Or at least choices that do not benefit and work towards your future. The second major thing is that once you have the money, credits, reputation, funding, to move fully into game development, you can do that whenever. But as tiring as it is to maintain a day job alongside a potential career in creativity, it's that much harder to write 50 grenade barks when you haven't eaten today."

- Read a lot

While it may sound like a cliché, reading a lot is essential to becoming a better writer, whether that's reading fiction or books about writing.

"I think we're in a wonderful age where lots of people have put out lots of books on what games narrative is, and how to be successful in creating a good game story," Brotherson says. "Getting to expand that toolbox and understanding all the mechanics that come with games writing and games narrative is really just a fantastic way of being able to prepare yourself for that job."

However, whatever you read, do not be a passive reader. As Wood explains, you need to read thoughtfully.

"Reading for entertainment and pleasure is good, and you'll absorb things unconsciously. But you'll learn a lot more by thinking why you liked something, why you disliked something, and how you can extract tricks and tools to replicate things in your own work."

Tremblay works with a community of games writers as part of DMG, a queer and feminist nonprofit organisation for marginalised game creators, and as part of that work she put together a reading list for folks who want to learn a bit more about the craft. It includes books, talks, and blogs and you can find it right here.

- Reach out to peers and seek mentorship

We've already highlighted the importance of networking. If you're lucky enough, networking may lead you to finding a mentor, which is an invaluable way to learn and progress.

After initial interest in a games writing position, Ayoola ended up in contact with Jana Sloan van Geest, senior game writer at story-driven casual games firm Wooga, and former scriptwriter at Guerilla Games and Ubisoft.

"She really took me under her wing as her mentee," Ayoola says. "She gave me her precious time, sharing all of her knowledge and pretty much gave me all of the advice I needed to both understand the role and start off as a game writer. She was also the one who invited me to the event where I would later meet Allan [Cudicio], founder of Twin Drums.

"I let my self-doubt and anxiety keep me from reaching out to people who I know would've been wonderful career advocates for myself"

Kaitlin Tremblay

"Don't be afraid to reach out to people; there are lots of really kind and supportive people in the game writing community who despite having worked on some really big titles are so warm and really want to support those who are still up and coming."

A good mentor will help you get a job, Stone says, but a great one will help you to keep the job. Looking back at her first experience in games, Tremblay says she had to do a lot of the learning by herself because she didn't have a mentor.

"I always missed not having a mentor-type figure I could ask specific questions to and somebody who could help me navigate legalese of contracts, studio politics, as well as the craft of narrative design and games writing," she says. "There wasn't a lack of qualified people, I just let my self-doubt and anxiety keep me from reaching out to people who I know would've been kind, supportive, and wonderful career advocates for myself."

- Listen to music

One final piece of advice from Nelson, which he describes as an "immensely powerful thing," is to listen to as much music as you can, including genres that you do not care about and that you perhaps look down upon.

"When you're working as a game writer, a lot of times, you will not just be working with material and genres that you personally care about. You also are going to be dealing with collaborators who have wildly different bases of inspiration and creative joy than you. Music is among the most digestible and accessible forms, so if you can listen to a metal song and find something to value in it and understand why people would like it, without disregarding it or going with an oversimplified answer, you will have the mental framework through which to approach a new genre of writing, and find something special to bring to the table."

To conclude, Wood wants to remind aspiring writers that getting into games is hard. But once you have your first gig, it's immediately easier.

"I have heard people say: 'don't apply for jobs you don't want as a stepping stone to the one you do.' But, honestly, a lot of people transition to writing from other disciplines. And if you're multi-skilled, you're more likely to be useful to small companies that can't afford specialists. You can learn a lot about games, and thus about how writing works within them, by working in other roles. If you can get other roles, take them!"

More GamesIndustry.biz Academy guides to Working in Games

Our guides to working in games cover various perspectives, from hiring to retention, to landing the job of your dream or creating the right company culture: