A brief guide to becoming a concept artist

Shiro Games' concept artists tell the GamesIndustry.biz Academy about how the field is about much more than "pretty drawings"

Concept art is one of the most sought-after artistic fields in the games industry.

When the GamesIndustry.biz Academy put together its guide to getting a job in game art, Teazelcat CEO and game director Jodie Azhar pointed out that concept art roles can have hundreds of applicants for one position, making it one of the most competitive roles alongside character artists.

Olivier Leonardi, expert art director at Ubisoft Reflections, then added that almost everything in game development starts with concept art, making it an ideal area of specialisation for young artists. But concept art is also widely idealised by outsiders, who don't realise what it actually entails.

"A common misconception is that concept art is about doing cool and pretty drawings or illustrations - it is not"

Pierre Armal, Shiro Games

"A common misconception is that concept art is about doing cool and pretty drawings or illustrations -- it is not," says Pierre Armal, concept artist at Shiro Games. "It is about ideas, and solving problems for the 3D artists and game designers. Drawing is only a tool used to that end."

And it's not the only misconception about the field, adds Cécile Jaubert, also a concept and VFX artist at Shiro Games. For instance, despite common beliefs, you don't need to be a flawless illustrator to be a good concept artist.

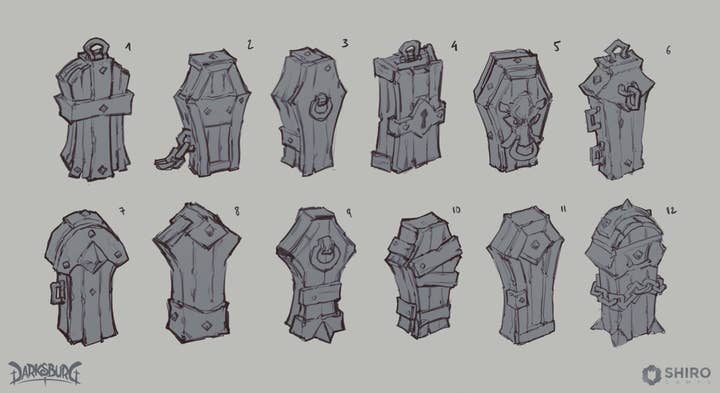

"80% of the job is designing 'small things'," she says. "There's only so many important characters in a game, but boy is there a lot of chairs and rooms and VFX sometimes. You will spend a lot of time working on things that might seem insignificant, but your work remains important for your coworkers.

"You don't need to be an incredible painter to be an excellent concept artist. The most important part of concept art remains good design skills. As long as you draw (or photobash) well enough for people to understand your design and transcribe it in 3D or in a final 2D work, then you're doing your job."

Armal actually wasn't drawing until he started studying to work in the games industry. He went to a 3D graphics school and started drawing after he realised concept art was what he wanted to do, so he started learning more about the field in his own time and through 2D art lessons.

On the other hand, it's Jaubert's love of drawing that led her to concept art. She initially wanted to work in animation but following "a series of failed tests," and inspired by a friend who was following that path, she ended up enrolling into a generalist video game school.

"We studied a lot of things there: 3D, animation, but not too much 2D," she says. "I am lucky in the sense that I've been drawing since I was young and it never really left me. Doing all these different things during school hours was motivating me to draw more for myself on the side.

"But through school it also became apparent to me that I do like the 'puzzle solving' aspect of design, so little by little it became obvious to me that a good way to combine drawing and design was concept art."

The role and responsibilities of the concept artist

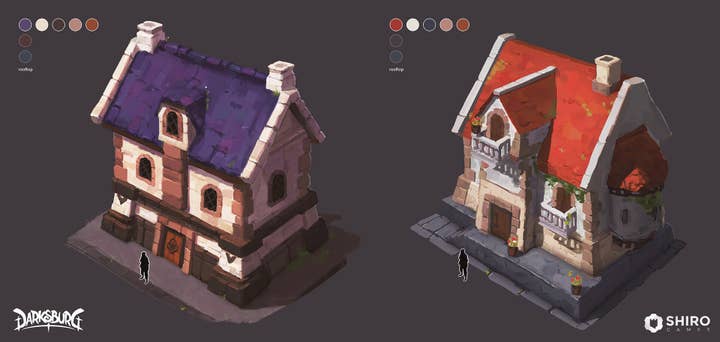

Armal explains that concept art consists in the whole visual designing process of everything the player will see: the characters, the environments, the colors, the moods, the style.

The role of the concept artist is crucial to exploring early game ideas, delving into what could work and what doesn't, and iterate quickly. That inherently means a lot of back and forth between art and design teams.

"Drawing is one of the fastest -- and by proxy, cheapest -- ways to explore various possibilities for an element of the game," Jaubert says. "Depending on the precision of the initial pitch, the exploration can go really wild or remain centered around the same core elements but with a bit of variation. It usually takes [some] back and forth to find a design that fits the directors and when that's done, the concept is sent to other team members that will be in charge of making the final 3D -- or 2D, depending on the game -- model and animate it, add sounds to it and insert it in the game.

"Drawing is one of the fastest -- and by proxy, cheapest -- ways to explore various possibilities for an element of the game"

Cécile Jaubert, Shiro Games

"It is possible that once integrated in the game, the team realises some things aren't fitting -- that would have been hard to figure out before being contextualised in the game -- so some retakes can happen, but more often than not the pipeline remains the same."

That also means that concept artists have to produce a lot of different visual options and directions based on the initial pitch, whether that's a character, an environment, an object, or an ability.

"Our art helps the rest of the team project into these possibilities in a more concrete manner and make choices from that," Jaubert continues. "Having a visual under the eyes helps the directors see which options fit more the feeling or information they want the player to have. It's much easier for everyone in the team to hear, 'This design feels scarier than this one, keep pushing in that direction' than, 'Make something scary' and go from there.

"We can never completely prevent big changes from happening and work being 'thrown away,' as it is the life of every project, but we limit this as much as possible by weeding options out beforehand."

While the role of the concept artist may be slightly different depending on the size of the studio, and evolves alongside development, it is the most crucial at the beginning of a project, as everything needs to be fleshed out.

"That's the moment when we need a lot of pre-production art to find the game's direction and design the characters and environments that will later be built," Armal explains. "Because we are a small studio at Shiro Games, as 2D artists we have to design the UI, all the icons and interface-related things too. When the production [reaches] the end, we participate in checking everything that can be polished visually, in both 2D and 3D."

Finally, as concept art is a way to explore the game's atmosphere, storytelling will often transpire through the art, meaning narrative elements are something concept artists often have to keep in mind when working.

"I think it's important, while designing, to ask yourself questions like 'who?', 'where?', 'how?', 'why?'," Armal says. "For example, for a character, what do they do? Where do they come from? What are they doing here and how do they intend to achieve whatever it is they want to achieve?"

Same goes with objects, Jaubert adds. You'll need to think about how it will be seen in-game: will it be up close? Or only from one angle? It's not all about telling a story or transmitting a strong intent for a character or environment.

"Sometimes it's just designing a chair that fits a room. But even then, you can find little things to put in them. Your tools will be the shapes and colours you use, but remember also that a lot of the design will also come to life through the animations, sounds and effects of the final version."

Qualities, skills and good practices

- The qualities of a good concept artist

Concept art is the ability to convey ideas in a visual form, meaning that good communication skills -- both in your art and verbally with your colleagues -- is crucial.

"A good concept artist in my opinion is someone who has good and interesting ideas, is able to come up with visual solutions to problems, and communicates that through clear and concise drawing and paintings," Armal says.

Jaubert adds: "Sometimes people aren't clear on what they want, so you won't always have clear cut pitches to base yourself on for your design. Try to understand what they want, while also minding what you think is good for the game."

Closely linked to communication skills, synthetic thinking and problem solving are a must to be a good concept artist.

"Don't lose yourself in the details, especially not at first"

Cécile Jaubert, Shiro Games

"Don't lose yourself in the details, especially not at first," Jaubert warns. "Like sculpting a rock, start with the big shapes and once those are validated, then you can work on the details. It might also be up to you to [decide] what the place of the element you're designing is in the game. A game designer will give you parts of the information, a QA might complement it after doing in-game tests, your art director will also have their own word about the element you're trying to design. But you need to summarize all these views together to work. On top of that you'll also need to learn the visual and design style of the game so that your concepts fit nicely in the universe."

Finally, curiosity is another key quality to being a good concept artist, as you'll need to learn about all sorts of unexpected things, from animal anatomy to engineering, to perfect your drawings.

"It's impossible to have knowledge about everything, [and] you'll need to learn for each project you work on," Jaubert says. "My best advice is to cultivate your curiosity, as it is easier to learn something when you make it interesting for yourself. Curiosity will also help you cultivate your own references and nurture your tastes, what will eventually grow to be your comfort zone, and what you like working on the most."

- Good practices for concept artists

In addition to cultivating the qualities listed above, Armal says that one of the best things you can do to improve is constantly feeding your "visual library" through reading, watching movies, or playing games. And regardless of your level as an artist, you should always be working on your drawing fundamentals.

"Sketch a lot, [do] drawing practice," he continues. "And have fun. If you don't like to draw -- which was my case in the beginning -- learn to love it, it will be incredibly worth it. My favourite [practice] by far is to build a larger personal project, something you work on during a few months. It trains you to work on designs that are cohesive together, and that's when I personally have the most fun and come up with better designs and ideas."

"Creativity and design are muscles that grow more flexible and strong when used often"

Cécile Jaubert, Shiro Games

Jaubert advises to sketch out your ideas often, even if they're random, which will also help find your own style. At a basic level, you only need a pencil and paper to practice, but the Shiro Games artists had a few recommendations when it came to software.

"Photoshop is an industry standard but there's a lot of them out there now," Jaubert says. "Krita, Gimp, FireAlpaca, Clip Studio Paint, Paint Tool SAI... My advice is to try the ones you're curious about and see their strengths and limitations. See how they work and which one clicks best with you.

"Creativity and design are muscles that grow more flexible and strong when used often. It doesn't mean you have to draw five hours a day though -- just a sketch can be enough. The thing is more to practice putting the idea down and 'making it visually real' rather than keeping it in your head, where it will always be a bit shapeless. The act of putting what is in your brain on the paper can be really tricky sometimes. Some ideas will be clear cut, others will escape your grasp like water and it will be a struggle to actually draw them 'like you want them to feel'."

Advice for new concept artists

When it comes to finding a job as a concept artist in the games industry, Armal advises to make sure that you have work in your portfolio that actually matches the needs and projects of the studio you're applying for.

"If there's a studio you really really want to work at, don't hesitate to tailor all your work towards that studio," Jaubert adds. "Also don't hesitate to do fanart. Some people might say you should only do original work, but fanart is an excellent way to study designs you like, share your passion about something with people that like it too, and get noticed by people that work on said thing you love a lot."

"That shit is no joke, take care of your body."

Cécile Jaubert, Shiro Games

Film and animation artists moving to games, which can be a very logical sidestep, may have an advantage in terms of employability, but game artists trying to get into concept art also have the advantage of understanding the pipeline already.

"If you're coming into the game industry [from film], don't diminish what the knowledge you already have can bring you," Jaubert says. "Designing stuff for a game isn't so different as for a movie -- real or animation. Just remember to be mindful that game design has priority over visuals. You're making a game. So the most important part of it is, does it feel good to play? Is your design helping that direction? And that's it.

"If you're already in the game industry, talk to the concept artists you know. Ask them about their job. They might have precious advice for you, and different from mine."

And as a final word, Jaubert says you should also be taking very good care of your body.

"Your hands and eyes are your tool of craft," she says "Even if you don't feel pain or problems, stretch them often -- each time you take a little break, or every two hours if you need a timed reminder, walk outside and do squats to shake off the long hours of sitting. Pushing until you feel discomfort or pain is the sure way to go towards injury that will take you out of practising for months at a time, and sometimes even years. That shit is no joke, take care of your body."

More GamesIndustry.biz Academy guides to Working in Games

Our guides to working in games cover various perspectives, from hiring to retention, to landing the job of your dream or creating the right company culture: