Panic Button and the search for "design fun"

GM Adam Creighton shares how the studio hailed for Switch ports approaches broadening its portfolio, tackling hardware challenges, and accessibility

When Adam Creighton joined Panic Button, the Austin, Texas-based studio was very much still figuring out what it wanted to be when it grew up.

At the time, it had released a number of fairly quiet original IPs across the Wii and Xbox 360 over its first four years, but was beginning to double down on work-for-hire ports. As studio GM and director of development, Creighton had something else in mind - a much broader portfolio. Work-for hire. Original IP. Specialized publishing. Developing for existing properties.

Seven years later and Panic Button may be best-known at the moment for its Nintendo Switch ports, but the studio has dabbled in almost all of the above and more. And that's exactly how Creighton intends to keep it.

"I'm a portfolio person, and I want to have a lot of diversity in the kind of work we do on the platforms," he said, speaking to GamesIndustry.biz at PAX West. "We have really good partnerships with Microsoft, Nintendo, Sony, and other folks, and for the viability of a studio you want to have that expertise across the board.

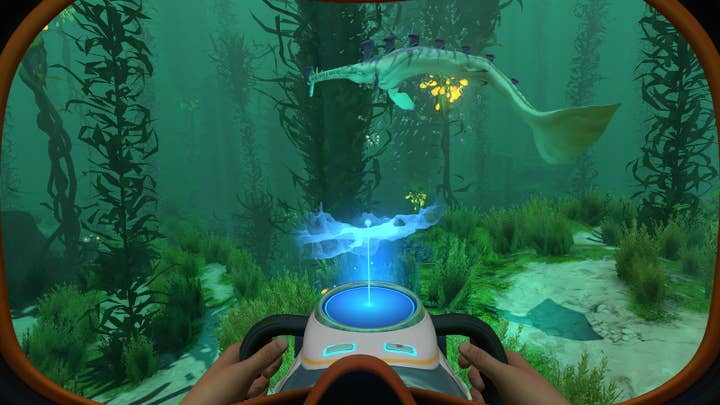

"Even with our recent successes, people remember the most recent thing you've done. And we always want to make that excellent. So people are looking at the Switch work we're doing and we're proud of that, but we're also doing Subnautica for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, we've done ReCore for Xbox One and Windows, and a lot of other projects on other platforms. We're gamers, and we like to make the kind of games we want to play, so we'll always be doing all sorts of diverse work."

Of course, as Creighton said, audiences do tend to hone in on the most recent thing a studio has done, and as a result Panic Button isn't especially notable for its original IP. The studio quietly released Astro Duel Deluxe as a Nintendo Switch launch window title, but before that it hadn't developed and published an original game since 2012. Even so, Creighton assured me that the studio's original IP weren't forgotten.

"We're not one of those companies that will put everything else on hold and do an original property that might or might not be successful"

"At some point, we want to do our own stuff, or something unique and original with someone else's stuff, and we're pretty flexible with how we do that," he said. "That original IP is an important part of our portfolio.

"We're not one of those companies that will put everything else on hold and do an original property that might or might not be successful, because I want to make sure I take care of the staff. We'll always be doing development with partners and some publishing work. The work we're doing is smaller-scale than some of the projects we're doing with our publishing partners. We don't plan to reinvent the genres for the games we're making, but we want to create some very tight, well-crafted love letters to these particular genres that we think will be fun and enjoyable and replayable for folks."

For now, the studio is happily handling port after port for a number of platforms, but most notably of late the Nintendo Switch. Panic Button is responsible for the Switch ports of Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, Doom, and the upcoming release of Warframe on the system.

With the studio's recent focus, it's no wonder Creighton is excited about the Switch as a system, both for its unique technical offerings and for the special brand of challenge it offers his studio. He told me this was especially true for games that were not originally developed with the Switch in mind or, in some cases, developed before the Nintendo Switch even existed.

"We like to make projects that are special for the target hardware, and Nintendo Switch is a cool device because you use it on the go, you use it docked, and you use it in both modes and move back and forth," he said. "So we've done things with the control schemes and motion, but also bringing these AAA big titles in their true form to this hybrid hardware has been really challenging. We like a challenge; it's part of why we go after these things. We wanted to both broaden those properties' availability to a whole new group of people, but we also wanted to broaden the Nintendo Switch as a platform. We really feel like core games make so much sense on that hardware that we want to bring those over.

"For a port, we have to bring the game faithfully with all its gameplay and features, or people feel like it's a lesser port"

"Ports are tough, because when someone's designing a game for the first time for a platform, we can cut features or mold features or make changes that people don't know about or see because we're able to make those in advance of release. For a port, we have to bring the game faithfully with all its gameplay and features, or people feel like it's a lesser port.

"And we actually talk about re-targeting a game for a platform. Because ports have either a positive or negative [connotation] depending on who you talk to, and we want to make the game special for the new hardware with as much functionality, but also add to it in a way that makes it special for the hardware. So you get something like Doom or Wolfenstein II and you get the full game, but you also get motion controls. We want to make it as close to the original as possible, working within the constraints of the hardware, but also doing special stuff where it makes sense, but that can't be gimmicky. It's just kind of all over the place."

Creighton said that such a balance is tricky, especially for a system like the Switch with several unique technical and control options. It can be difficult to resist the temptation to use its capabilities simply for their own sake, he said, but it can also be difficult to implement those features even where they make perfect sense.

"When we were working on Doom, we had pitched that we wanted to do motion controls, but as we were getting close to release, they just weren't where they needed to be yet. So we released with melee motion in the shipping version of Doom, then we worked on motion gaming behind the scenes and released a patch in February where we had much more comfortable, much tighter, much more organic feeling motion controls for Doom.

"Same with HD Rumble, or touch. We want to make sure it works and isn't frustrating and feels good and native to the platform. If we're not redoing user interface, sometimes touch doesn't make sense for a particular game because there are certain areas you have to fit within, and if you have these tiny little menus, it's too easy to do false positives on touch screens. We look at everything each platform can do. We just want to make sure it feels good to the game, good to the platform."

As Panic Button grows its portfolio, Creighton said, the studio is also starting to gain a certain notoriety and audience. It can be tough, he said, for studios like his that don't focus just on developing original games to gain name recognition, but Creighton believes in the importance of building brand awareness not just with business partners, but also with the general gaming community.

"We're building this brand where we make people aware that we're working on these titles or bringing these titles to them, and they get to play these titles on the hardware they want because Panic Button is involved. We treat that very seriously. We don't go the route of, 'Oh look at us, we're amazing, and you're lucky we're bringing these games,' because for me working on games is a gift. I hope maybe some of that comes through, and a lot of our team has that same attitude. And we're going to do more community events, more events with the public, so I think you'll see more of that involvement and visibility not just for me, but other members of the team."

Speaking of the rest of the Panic Button team, Creighton told me one thing the studio likes to nuture internally is independent development. Earlier this year, Panic Button handled the PS VR port of the game To the Top, which was co-created by studio programmer Dan Dunham. Aside from being an employee-created game, To the Top is also unique in that so far, it's the only VR game the studio's worked on. But Creighton said neither of those unique factors was the ultimate determiner of whether or not Panic Button worked on it.

"For us, it's what makes sense for the hardware," he said. "There's a lot of interest and excitement for VR right now, and we want to make sure the game makes sense and is fun. To the Top is an interesting thing for me because it is a first-person parkour platforming title in virtual reality. On paper it does not make sense. But it plays amazingly well. People don't get sick or disoriented. Dan and Richard [Matey, co-creator] did an amazing job on the title and it's a very solid, well done game.

"I like to do titles that people look at and say, 'What?!' followed by 'Of course, that makes perfect sense'"

"Part of why we did To the Top wasn't just because it was an employee title; it was because it was a thing we looked at and said, 'Oh, this is a thing that is unique and special because it's in VR.' Those are the kind of titles we want to make. I like to do titles that people look at when they're announced and say, 'What?!' followed by, 'Of course, that makes perfect sense.'"

Creighton sees lots of opportunity in VR, but he is waiting for the right title to dive back into the medium - another game that makes "perfect sense" in the way To the Top did. But even while not actively involved in VR, he's still fascinated by the direction it's taking, and optimistic about its effects on the industry.

"There are a lot of opportunities in VR. Once people go tetherless, we're excited about gameplay options that relate to that - being able to move around, having a mix of virtual reality and augmented reality is going to be fun. People are doing some interesting things with virtual reality that have windows so you're not going to trip over a coffee table as you're looking out. We're looking for the design fun, honestly.

"I'm also interested in asymmetric gameplay, where some people are in virtual reality and some aren't, and being able to play back and forth. Then you have publisher-developers like Ubisoft that are very forward-thinking where their VR titles are across multiple platforms with cross-platform play. People can jump into a game like Star Trek Bridge Commander and be playing in different headsets or not in VR and all be playing together, and I think that's going to really broaden the accessibility for VR. It's challenging, because you have to make it really compelling in VR and not VR, and there's a limited set of games that that probably makes sense for, but Ubisoft seems to be cracking it. It's pretty cool."

Since Creighton brought up accessibility multiple times as we conversed about VR, I asked how Panic Button approached the issue in its own games, ports or originals. Creighton had a lot to say on the subject, citing how important he felt accessibility conversations and considerations were not just at Panic Button, but for small developers in general and for all studios. He said questions of how buttons are mapped and how control schemes work are always a consideration for Panic Button's games, but for him, accessibility goes beyond that.

"We want people to be able to play games wherever they are with whatever they have with them"

"At the end of the day, gaming's a commercial venture, and so people have to make decisions about what they're going to do and how they'll make things accessible. I don't mean that in a negative or cutthroat way, but people have to look at: Are we going to be able to do this? Is it going to be able to take care of people in a way they can play? Is it financially viable and how do we make all that work? I think those will be questions that get asked a lot more as part of regular development.

"But for me it's not about physical accessibility only. It's also about social accessibility and lifestyle and other stuff. I think we're going to see, content-wise, more accessible stuff. I look at games like Life is Strange. It's a tremendously powerful, artistic, well done game that speaks to that accessibility for a group of gamers that enjoy that title and didn't feel represented, but now do. But there are mainstream folks who say, that title didn't resonate with me. So I don't know what that says. As we make something accessible to one group, does it not make it accessible to another group? I think it makes it accessible to both. I want more people to be able to play.

"We want people to be able to play games wherever they are with whatever they have with them. That's part of why we do all the different kinds of games we do, and why we do so much for the Nintendo Switch and why I like that platform so much, because I can play in my living room with my family, or I can travel and take my Nintendo Switch with me. It's very cool to have quality game experiences everywhere, and now we're seeing this proliferation of cross-platform play. I look forward to people doing even account portability, where I can go from one device then travel on another device and progress, then go back to my home device and I'm all leveled up because I'm traveling.

"Everyone's going to do what's best for their ecosystem, and there are technical challenges and policy challenges and taking care of brands and those kinds of things, so every ecosystem will make its own business decisions. But for us, working with what we can work with, what can we do to make games more accessible?"

Disclosure: PAX organizer ReedPOP is the parent company of GamesIndustry.biz.