Tenchu: No prescription needed

Why I Love: Solar Sail's Tancred Dyke-Wells finds freedom in an overshadowed PSone ninja game

Why I Love is a series of guest editorials on GamesIndustry.biz intended to showcase the ways in which game developers appreciate each other's work. This entry was contributed by Solar Sail Games co-founder Tancred Dyke-Wells, who used to direct Nintendo's Art Academy and Battalion Wars games, and is currently at work on the open-world narrative-driven RPG Smoke and Sacrifice.

I can't claim this was the moment I fell in love with Tenchu: Stealth Assassins because I'd already fallen for that game pretty hard by this point, but there was a certain moment - an incident - which roused me to howls of rage and swearing so colourful I surprised myself and burned this game indelibly into my experience.

It was 1998; I'd only been in the industry a couple of years at that time, working on a sim/point-and-click adventure hybrid, BiOSys. That game was pretty far removed from Tenchu, a seminal stealth game created at the height of the PS1 era by Japanese development house Acquire, (the license subsequently acquired by From Software).

The game lacked the production values of the contemporary stealth blockbuster Metal Gear Solid, but also the prescription - and so for me it was something special.

Featuring a distinctive original soundtrack from Noriyuki Asakura which fused Western pop with Chinese, Thai, Japanese and even Arabic influences, the game wore its musical charisma brazenly. The soundtrack was acoustic, vocal (in West African Hausa!) and unashamedly prominent - the antithesis of the forgettable scores that characterise contemporary action movies (and often sadly, AAA games). Voice acting was similarly bold, Seiichi Hirai and the rest of the cast dividing audiences with unabashed overacting. But love it or hate it, few games are so quoted. "It looks like you chose the wrong party to crash...!"

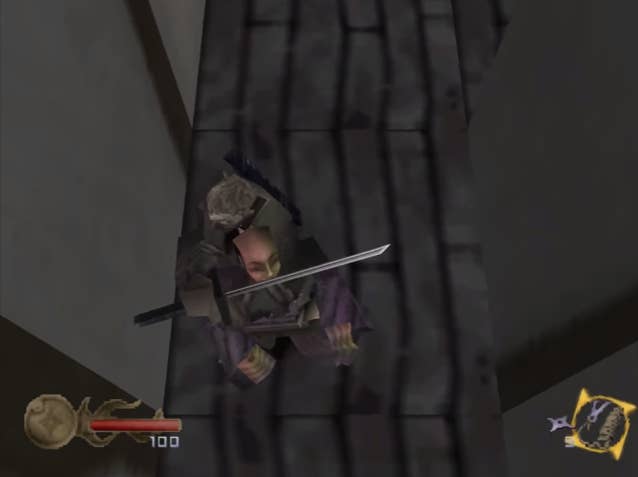

Anyway, I'd fought and failed to kill Onikage before, ninja grappling and stealth-killing my way to the top of the castle at the end of Level 9 to do so. Tenchu's bosses were not the rock-hard exercises in suffering that current IP holders From Software's oeuvre is known for, but the arrogant bastard fought bare-handed, and his double spin kicks dealt a lot of damage.

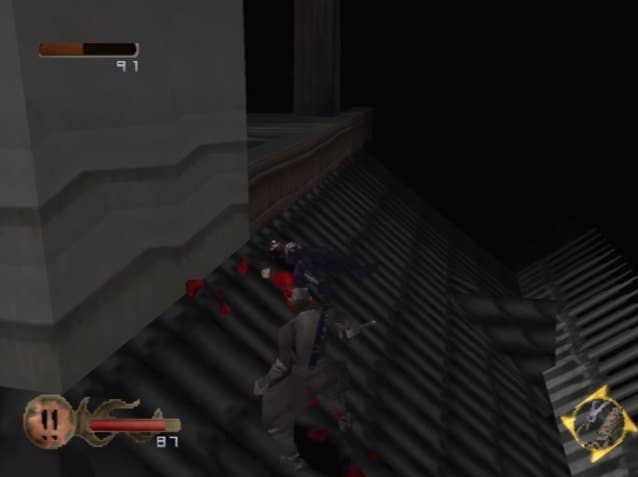

I'd seen that he could use his own health potions, and I'd also discovered that it was possible to lure or knock (or more likely be knocked by) him outside the rooftop that at first appeared to be the designated fight zone. One fight had carried on right down the stairwells of the castle. This in itself was flabbergasting, a boss fight not being confined to an arena. And it reflected the openness that made the game a stand-out experience.

But what really had me screaming at my cathode ray TV was when, worn down by the fight and mid-way through attempting to consume a health restorative of my own, he'd kicked it from my hands, and then shortly afterward snatched it from the floor and guzzled it himself! The temerity!

This was an unscripted moment. Onikage was just an AI agent driven by a state machine that allowed him to share some actions with the player. Giving him these abilities may even have been a development economy over creating more bespoke actions for the character.

"Tenchu's grapple could be used on any surface, not just predefined points. The game seemed unafraid to allow the odd glitch in order to maximise player freedom"

But this application of a seemingly consistent ruleset between the player and AI characters - that they could take up and use my own tools against me - was, for me, deeply compelling and something rarely seen since. The even-handedness conjured up the feeling of a world that felt alive, with internal consistency - somewhere with a sense of possibility.

This was a little before true open-world, sandbox games such as Outcast and Grant Theft Auto III would appear. Ocarina of Time was the darling of the moment, and while I could appreciate the elegance of that game's design, at some level I couldn't help feel that my play experience was likely to conform very closely to that of other people. Dare I say it, at times it felt like an exercise in beautifully-refined hoop-jumping - a shepherded, predetermined experience - and all that breaking pots in people's houses just didn't give me the feeling of a living world.

Similarly Metal Gear, honed and polished as it was also for me lacked the feeling of an internally coherent world. Rooms would reset on exit and entry, alerted guards instantly becoming oblivious to your presence on stepping in or out of a door. The illusion broke easily.

But Tenchu's enemy layouts varied with each attempt and characters could pursue you from one end of the map to the other - the weapon selection on offer (smoke bombs, caltrops, poison rice cakes, grenades, mines, coloured rice) seemed to offer and encourage experimentation.

Emblematic of its overall design philosophy, its grapple could be used on any surface, not just predefined points. The game seemed unafraid to allow the odd glitch in order to maximise player freedom.

Twenty years on, this attitude still informs my own approach. With Smoke and Sacrifice, we're melding an organic, open world with rich, crafted storytelling. For me, the ideal game experience finds that sweet spot where meaningful emotional engagement is brought together with the freedom to experiment and set your own goals - but most importantly, in a world that feels alive.

Upcoming Why I Love columns:

- Tuesday, May 22 - Sperasoft's Steven Thornton on Portal 2

- Tuesday, June 5 - Over the Moon Studios' John Warner on Dark Souls

- Tuesday, June 19 - Infinite State Games' Mike Daw on Bubble Bobble

- Tuesday, July 3 - Infinite State Games' Charlie Scott-Skinner on Monster Hunter

Developers interested in contributing their own Why I Love column are encouraged to reach out to us at news@gamesindustry.biz.