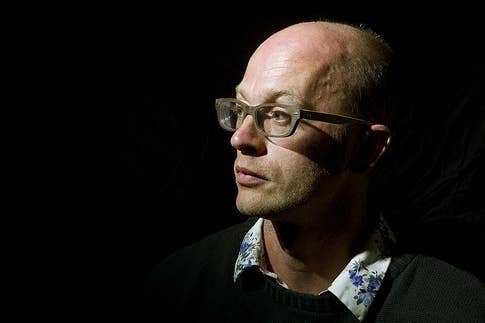

Master Of Horror: Dan Pinchbeck

“The hate mail we got made Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs look like Sesame Street”

For those of us that like our nerves jangled and our nights sleepless, there's been a pleasing resurgence of horror in the industry of late. Outlast and Slender: The Eight Pages, Shinji Mikami's The Evil Within, Alien: Isolation. But perhaps the most disturbing of recent times was last year's Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs, created by The Chinese Room.

"When we wrote Pigs we used to laugh imagining sitting in a meeting and trying to push some this content past a publisher, and the chance of them going, 'what's the game about?'" said Dan Pinchbeck, creative director at the UK studio.

"'Well it's about, you know, a man who kills his children.'"

So, not a game to play with your kids when they've finished LEGO Star Wars, but an attempt to offer a different, almost literary type of horror more akin to a compendium of HP Lovecraft stories than an installment of Saw.

"It's not Saw and Hostel. To me, it's a much more proper - I'll be in trouble for saying 'proper' - lot more of old school kind of concept of what horror is. It's something that is slow and unsettling, a building sense of dread and disgust, and being disturbed rather than running down a corridor, screaming," explains Pinchbeck.

"There was kind of a real seriousness to the heart of the story and what we want to say in that. But this is at heart a Victorian penny dreadful, a cheap trashy paperback. And that's okay, it's a game with kind of what mutant cannibal pigs in it. We've got to be a little bit realistic about the kind of game we're making. You can say all this big, serious stuff. But we still do have mutant pigs in it."

Yes, cannibal pigs, madness, infanticide, dark children borne of Pinchbeck's brain. But as he points out, compared to the film industry, games have avoided going down the torture porn route. The stuff you'll see in even the most extreme horror game pales in comparison to the misogyny and twisted set pieces of the average horror release.

"I love the fact that the games industry for the most part doesn't go down the torture porn route, that entertainment is a representation of violence. The sheer kind of levels of sadism that you get in contemporary horror cinema, games don't focus on that, to say that the sadism is the entertainment, getting off on the portrayal of rape is the entertainment. Cinema does that completely shamelessly all the time."

"If you, I mean if you are representing violence the way that it's represented in the cinema, in games I think there'd be a public outcry. And that, I think, is about this idea that because you're playing it, because you're in control of it, you're somewhat implicated in that."

As we chat Pinchbeck argues that in fact most AAA horror games in recent times avoid the horror route altogether, going for action over any lingering sense of fear or actual terror. He points to Dead Space and Resident Evil as examples of this horror-lite, games that are fun, but hardly horrific.

"Resident Evil just became toothless so fast, Resident Evil was always cheesy, it was never scary in terms of its story. But I think stuff like Dead Space started veering away whenever it got too close to making you slightly uncomfortable. You could almost feel it desperately backpedaling away from it."

But he doesn't blame those big publishers, suggesting that if you're making a game that costs $30 million you have to make sure you can recoup those costs, by pleasing the entire gaming audience rather than a small niche.

"I have to make sure that I'm making a horror game that's got to sell so many units, so I have to make sure that as palatable to a 12-year-old boy as it is to a 45-year-old woman. And that's ridiculous demographics trying to hit in any meaningful way."

By creating games on a smaller budget developers can make a more definitive product, aimed at their audience and not your 19 year old brother Steve and your 43 year old aunt Mabel.

"It's better to make a game that a smaller number of people love than a large number of people think is kind of alright. And if you can make that work in a business model it's a much nicer place to be as a developer. And I think it's a much nicer place to be as a customer as well, you feel like actually there's enough diversity."

For Pinchbeck being indie is as much about creative freedom as anything. Yes, The Chinese Room would probably lose to EA or even Capcom in a game of British Bulldog, but they can publish a game with themes that would make a room full of marketing executives upping their valium doses for the week.

"I guess because as an indie you're not that significant, you're under the radar for the most part. Certainly in terms of popular culture, you do have the freedom to go we can't compete on those levels with the big titles but what we can do is go to the places that they can't," he explains.

In fact, the content that caused the most unpleasantness when the game was released in September 2013 wasn't the ideas or the cruelty to bacon...

"You can say all this big, serious stuff. But we still do have mutant pigs in it"

"I thought what we sort of had a screenshots going out, of a pig nailed to a cross, that we were likely to get a couple of phone calls but amazingly people just went yeah, whatever."

...but something far more basic. And of all the things I discuss with Pinchbeck during our long interview, it's the one time he sounds genuinely frustrated.

"We got some really... the worst kind of hate mail we've ever got as a studio, some really very, very nasty stuff. That made the actual content of Pigs look like Sesame Street really," he says, audibly baffled.

People complained that not all objects in the room could be flung around like confetti, or that the sanity meter from the first Amnesia was gone, or that it wasn't an exact copy of Amnesia.

"The stuff I found most difficult was the idea that people wouldn't even kind of engage with the ideas or the content of the game because they seem so incensed by the way in which it was packaged. In terms of going, 'I just don't like the way in which this kind of game play is structured on quite a mechanical level.' And that's kind of... I still, I struggle a little bit with that in terms of understanding it."

Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs is still available on Steam, while The Chinese Room is currently at work on a project for PlayStation 4, titled Everybody's Gone To The Rapture.