Why won't the games industry share its digital data?

NPD, SuperData and Steam Spy offer up their thoughts

When I first began my career in the games industry I wrote a story about an impending digital download chart.

It was February 2008 and Dorian Bloch - who was leader of UK physical games data business Chart-Track at the time - vowed to have a download Top 50 by Christmas.

Nine years later, still no chart.

It wasn't for want of trying. Digital retailers, including Steam, refused to share the figures and insisted it was down to the individual publishers and developers to do the sharing (in contrast to the retail space, where the stores are the ones that do the sharing). This led to an initiative in the UK where trade body UKIE began using its relationships with publishers to pull together a chart. However, after some initial success, the project ultimately fell away once the sheer scale of the work involved became apparent.

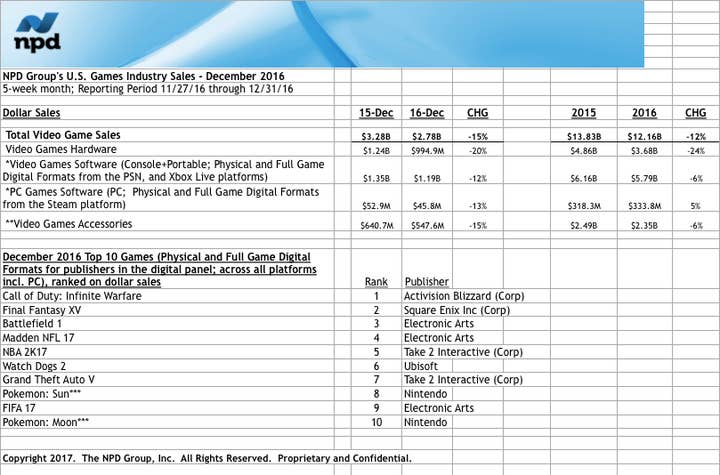

Last year in the US, NPD managed to get a similar project going and is thus far the only public chart that combines physical and digital data from accurate sources. However, although many big publishers are contributing to the figures, there remains some notable absentees and a lack of smaller developers and publishers.

In Europe, ISFE is just ramping up its own project and has even began trialling charts in some territories (behind closed doors), however, it currently lacks the physical retail data in most major markets. This overall lack of information has seen a rise in the number of firms trying to plug the hole in our digital data knowledge. Steam Spy uses a Web API to gather data from Steam user profiles to track download numbers - a job it does fairly accurately (albeit not all of the time).

SuperData takes point-of-sale and transaction information from payment service providers, plus some publishers and developers, which means it can track actual spend. It's strong on console, but again, it's not 100% accurate. The mobile space has a strong player in App Annie collecting data, although developers in the space find the cost of accessing this information high.

It feels unusual to be having this conversation in 2017. In a market that is now predominantly digital, the fact we have no accurate way of measuring our industry seems absurd. Film has almost daily updates of box office takings, the music market even tracks streams and radio plays... we don't even know how many people downloaded Overwatch, or where Stardew Valley would have charted. So what is taking so long?

"It took a tremendous amount of time and effort from both the publisher and NPD sides to make digital sales data begin to flow," says Mat Piscatella, NPD's US games industry analyst. NPD's monthly digital chart is the furthest the industry has come to accurate market data in the download space.

"It certainly wasn't like flipping a switch. Entirely new processes were necessary on both sides - publishers and within NPD. New ways of thinking about sales data had to be derived. And at the publishers, efforts had to be made to identify the investments that would be required in order to participate. And of course, most crucially, getting those investments approved. We all had to learn together, publishers, NPD, EEDAR and others, in ways that met the wants and needs of everyone participating.

"Over time, most of the largest third-party publishers joined the digital panel. It has been a remarkable series of events that have gotten us to where we are today. It hasn't always been smooth; and keep in mind, at the time the digital initiative began, digital sales were often a very small piece of the business, and one that was often not being actively managed. Back then, publishers may have been letting someone in a first-party operation, or brand marketing role post the box art to the game on the Sony, Microsoft and Steam storefronts, and that would be that. Pricing wouldn't be actively managed, sales might be looked at every month or quarter, but this information certainly was not being looked at like packaged sales were. The digital business was a smaller, incremental piece of the pie then. Now, of course, that's certainly changed, and continues to change."

The underdevelopment of publishers' own digital tracking methods is something that SuperData has observed.

"There are multiple reasons why publishers are reluctant to share data," says SuperData CEO Joost van Dreunen.

"For one, the majors are publicly traded firms, which means that any shared data presents a financial liability. Across the board the big publishers have historically sought to protect the sanctity of their internal operations because of the long development cycles and high capital risks involved in AAA game publishing. But, to be honest, it's only been a few years that especially legacy publishers have started to aggregate and apply digital data, which means that their internal reporting still tends to be relatively underdeveloped. Many of them are only now building the necessary teams and infrastructure around business intelligence."

Indeed, both SuperData and NPD believe that progress - as slow as it may be - has been happening. And although some publishers are still holding out or refusing to get involved, that resolve is weakening over time. "For us, it's about proving the value of participation to those publishers that are choosing not to participate at this time," Piscatella says. "And that can be a challenge for a few reasons. First, some publishers may believe that the data available today is not directly actionable or meaningful to its business. The publisher may offer products that have dominant share in a particular niche, for example, which competitive data as it stands today would not help them improve.

"Some publishers may believe that the data available today is not directly actionable or meaningful to its business"

Mat Piscatella, NPD

"Second, some publishers may believe that they have some 'secret sauce' that sharing digital sales data would expose, and they don't want to lose that perceived competitive advantage. Third, resources are almost always stretched thin, requiring prioritisation of business initiatives. For the most part, publishers have not expanded their sales planning departments to keep pace with all of the overwhelming amount of new information and data sources that are now available. There simply may not be the people power to effectively participate, forcing some publishers to pass on participating, at least for now.

"All of these situations are understandable. But none of them prevent future participation.

"So I would certainly not classify this situation as companies 'holding out' as you say. It's that some companies have not yet been convinced that sharing such information is beneficial enough to overcome the business challenges involved. Conceptually, the sharing of such information seems very easy. In reality, participating in an initiative like this takes time, money, energy and trust. I'm encouraged and very happy so much progress has been made with participating publishers, and a tremendous amount of energy is being applied to prove that value to those publishers that are currently not participating."

NPD's achievements is significant because it has managed to convince a good number of bigger publishers, and those with particularly successful IP, to share figures. And this has long been seen as a stumbling block, because for those companies performing particularly well, the urge to share data is reduced. I've heard countless comments from sales directors who have said that 'sharing download numbers would just encourage more competitors to try what we're doing.' It's why van Dreunen has noted that "as soon as game companies start to do well, they cease the sharing of their data."

Indeed, it is often fledgling companies, and indie studios, that need this data more than most. It's part of the reason behind the rise of Steam Spy, which prides itself on helping smaller outfits.

"I've heard many stories about indie teams getting financed because they managed to present market research based on Steam Spy data," boasts Sergey Galyonkin, the man behind Steam Spy. "Just this week I talked to a team that got funded by Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg based on this. Before Steam Spy it was harder to do a proper market research for people like them.

"Big players know these numbers already and would gain nothing from sharing them with everyone else. Small developers have no access to paid research to publish anything.

"Overall I'd say Steam Spy helped to move the discussion into a more data-based realm and that's a good thing in my opinion."

"As we all move into the next era of interactive entertainment, the need for market information will only increase, and those that have shown themselves willing to collaborate are better prepared for the future"

Joost van Dreunen, Superdata

The games industry may be behaving in an unusually backwards capacity when it comes to sharing its digital data, but there are signs of a growing willingness to be more open. A combination of trade body and media pressure has convinced some larger publishers to give it a go. Furthermore, publishers are starting to feel obligated to share figures anyway, especially when the likes of SuperData and Steam Spy are putting out information whether they want them to or not.

Indeed, although the chart Dorian promised me 9 years ago is still AWOL, there are at least some figures out there today that gives us a sense of how things are performing.

"When we first started SuperData six years ago there was exactly zero digital data available," van Dreunen notes. "Today we track the monthly spending of 78 million digital gamers across platforms, in spite of heavy competition and the reluctance from publishers to share. Creating transparency around digital data is merely a matter of market maturity and executive leadership, and many of our customers and partners have started to realize that."

He continues: The current inertia comes from middle management that fears new revenue models and industry changes. So we are trying to overcome a mindset rather than a data problem. It is a slow process of winning the confidence and trust of key players, one-at-a-time. We've managed to broker partnerships with key industry associations, partner with firms like GfK in Europe and Kadokawa Dwange in Japan, to offer a complete market picture, and win the trust with big publishers. As we all move into the next era of interactive entertainment, the need for market information will only increase, and those that have shown themselves willing to collaborate and take a chance are simply better prepared for the future."

NPD's Piscatella concludes: "The one thing I'm most proud of, and impressed by, is the willingness of the participating publishers in our panel to work through issues as they've come up. We have a dedicated, positive group of companies working together to get this information flowing. Moving forward, it's all about helping those publishers that aren't participating understand how they can benefit through the sharing of digital consumer sales information, and in making that decision to say "yes" as easy as possible.

"Digital selling channels are growing quickly. Digital sales are becoming a bigger piece of the pie across the traditional gaming market. I fully expect participation from the publishing community to continue to grow."