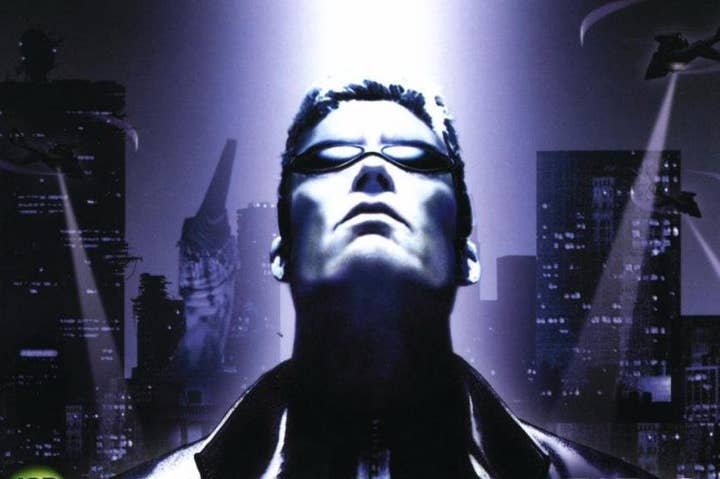

Why I Loved: Deus Ex

Alexis Kennedy of Failbetter Games kicks off a new monthly feature series

Why I loved... is a new monthly series written by industry figures about their favourite games. Some will be about a game that changed the way a developer worked, or inspired them to create something new; some will be about a game that got them through hard times, or put something poignant into perspective. Some will just be about something they especially enjoyed. Here, kicking us off in grand style, is Failbetter Games' Alexis Kennedy, on the classic Deus Ex.

"Everything they were wearing, he decided, qualified as what she'd call 'iconic', but had originally become that way through its ability to gracefully patinate. She was big on patination. That was how quality wore in, she said, as opposed to out. Distressing, on the other hand, was the faking of patination, and was actually a way of concealing a lack of quality."

-- William Gibson, Zero History

'Patina' is a layer that accumulates on objects with time and use - a sheen or a verdigris or weathering. Objects with a patina no longer look new, but they sometimes look better. It's difficult to fake patination.

When GamesIndustry.biz suggested I write a piece about a game I loved, I felt abashed picking something as widely admired as Deus Ex. (See also my upcoming articles on how the Beatles are actually pretty great and the Pacific Ocean is still wet.) But it's not an entirely uncontroversial choice.

Tom Chick, possibly the finest game reviewer in the world who has never written for Eurogamer, notoriously gave DE a 3/10. He's unimaginably wrong, of course, but he's not alone. Others have pointed out that DE isn't a perfect game by any stretch of the imagination. The AI is both neurotic and senile; the story is a kind of deep-sea gumbo of conspiracy theories; and although DE constantly pretends to be realistic, it constantly fails at what other games would call immersion.

"In the opening ten minutes your first task - as an elite agent of an international anti-terrorist force - is to break open crates with a toolbar"

In the opening ten minutes your first task - as an elite agent of an international anti-terrorist force - is to break open crates with a toolbar. Your second is to place a knee-high crate next to an inexplicable stepped concrete structure so you can climb it to reach an inexplicable crate at its top. Your third is probably to take down a terrorist unseen, but if he spots you, you can duck back round a corner and he won't follow you far enough to cause trouble. And so it goes. For over a decade, players have taken delight in the ability to bounce a basketball off their briefing officer's forehead while he lectures you on talking to the press.

I'd say it 'fails' at immersion, but it more 'concedes' immersion. Here are some other things you can do in the first hour:

- work out the best place of an enemy's body to target with a riot prod

- hack an ATM for cash

- blow open a locked box on a sunken boat with a grenade

- blind an enemy with a fire extinguisher

- break both legs jumping off the side of the Statue of Liberty and crawl to the level exit

All of these things are the outcomes of consistently executed systems. The DE team could have compromised on the systems and made the game feel more realistic, wallpapering over the cracks that allow you to chat idly to your brother with your legs snapped off at the knee. Instead, they provided a vast and consistent toy world that you're learning from ten minutes in.

OK, systemic gameplay: it's the old new thing. Roguelikes, open world games, procedural RPGs - we have plenty of games that rely on behaviour emerging from the elegant interaction of systems. But Deus Ex doesn't rely on the elegant interaction of systems. It relies on a loving, intelligent but demented patina of systems, layered over years of development.

"But Deus Ex doesn't rely on the elegant interaction of systems. It relies on a loving, intelligent but demented patina of systems, layered over years of development"

From the beginning of preproduction to release, Deus Ex took 'only' three years, but the director-producer, Warren Spector, had been trying to get it made for four years before that at two previous developers... so by the time the game was released, it had been in the oven for seven years. It had accumulated five hundred pages of design notes; it had accumulated a legion of characters that the team added to and added to, long before they worried about how they'd fit into the game.

Consequently the balance of DE is gently bonkers. Some weapons are way more powerful than others; some items are junk. Every level, famously, has two or three approaches, but some are much easier than others. There's a skill system (improved with XP) and an augmentation system (improved with upgrade canisters). Why two systems? The sequels did away with the skill system altogether, because common sense says you wouldn't have two entirely separate upgrade systems. But every skill and augmentation feels distinctive and intuitively appealing, and the sheer variety of them trumps the demands of common sense.

Did I mention that your body tracks damage separately to head, abdomen and each limb? Damage to limbs will only spoil movement and aim - damage to head and abdomen will kill you. Again, this doesn't add any particularly elegant gameplay effects. Often you survive a firefight with a limp, which is pretty cool, and occasionally you apparently have both your legs blown off, leading to a desperate Pythonesque hump-for-cover.

The same goes for the world. It drips with colour and incident, and there's so much of it. New York, Paris, Hong Kong ruined petrol station, jetliner, cathedral, nightclub, undersea lab, supertanker; graveyard, mansion. There was a White House level; there was a level in a space station. Neither made it into the finished game, but there are still way more levels than any sane player has a right to expect.

"it's daft, even in DE's corrupt, resource-constrained, 'ten minutes before the apocalypse' world that an elite agent like the protagonist has to scrounge constantly for currency and ammo"

And, all right, it's daft, even in DE's corrupt, resource-constrained, 'ten minutes before the apocalypse' world that an elite agent like the protagonist has to scrounge constantly for currency and ammo. I won't lie to you - it's frustrating, and the interactions with the quartermaster who so grudgingly gives you the occasional lockpick or pistol (literally, a lockpick) are brow-knotting in their silliness. But DE is about exploring, navigating, and cracking open the environment. The constant resource sink of varied items means that you're never just looking for health packs. And the ingenuity that permeates the game means that every second resource cache has a tersely told environmental story.

There are people who will try to tell you that that DE's storyline is silly. Technically, I suppose they're correct. I feel, though, that there should be more joy in their lives. The storyline is meant to be an unlikely kitchen-sink mash-up of X-Files conspiracy theories, and it is, but it's mashed up with verve and grace. Those seven years of scheming and preproduction show. The characters are uneven but elaborate, with the rough organic edges that come from editing and reworking the larger plot, like the sprues of extrusion-moulding. The revelations come steadily one after another for thirty hours of gameplay. There are books and newspapers everywhere, and none of them outstay their welcome: they all deploy this secret weapon at the end of a paragraph or two of text:

"..."

I played Deus Ex at least once a year for about ten years. It was probably the third year before I realised that the choreographed death of a major NPC in an ambush is not, in fact, choreographed, and it's possible to save him, with a certain amount of swearing and vigorous reloading. I think it was the fifth year before I ceased to find anything significant and new (I found that I could swim out of of a hole in the wall of the undersea lab, through the ocean and find a hidden chunk of the level with a couple of additional diary entries.).

These were the days before walkthroughs and YouTube (literally: DE was released five years before YouTube launched). There are fewer internal frontiers and mysteries in the game, now. But it's still a whole continent of varied experience, emerging from the staggering quantity of content in the game, and the degree to which that content has been folded and refolded like a Japanese sword.

"it's still a whole continent of varied experience, emerging from the staggering quantity of content in the game, and the degree to which that content has been folded and refolded like a Japanese sword"

I can imagine a more minimal, elegant, cleanly balanced Deus Ex which allows for more unique experiences, rather than replays; I can imagine it might have randomised loot placement, procedurally generated maps, longevity of experience at the expense of customised variety. I imagine it would be more like XCOM, perhaps, or the Long Dark, or Invisible, Inc. - a beautifully tuned repeatable experience rather than a curiosity-shop of loosely allied experiences. I really like all those other games, and I'd play that hypothetical proceduralised Deus Ex. But I wouldn't love it the same way: it wouldn't have the same messy, human, brilliant sense of use and history. It's difficult to fake patination.

Alexis Kennedy is creative director at Failbetter Games, an indie studio with a reputation for exceptional writing and storytelling, darkly humorous games, and occasional cannibalism. Failbetter, founded in 2010, is best known for Fallen London, where the player makes a life in a capital stolen by bats, and Sunless Sea, a story-driven naval roguelike which won Eurogamer's last ever 10/10 rating.'

If you'd like to contribute to Why I loved... or know someone who might, email Dan Pearson at Dan@gamesindustry.biz