Why did licensed games get better?

BD Labs' Mark Caplan traces the industry trends that turned big-name properties from a warning sign to a welcome addition

Over the course of his career working in licensed video games, BDLabs principal Mark Caplan has seen some of the best and worst of what the union of a popular brand and a game developer can produce. When he started on Fox's licensing and merchandising team in 1993, the company was just coming off a two-year span in which it produced no fewer than eight licensed Simpsons games. Early on in his career, he worked on licensed game projects that were particularly well regarded (Alien vs. Predator on the Atari Jaguar) and ones that were... less so (White Men Can't Jump on the Atari Jaguar).

Speaking with GamesIndustry.biz recently, Caplan said the former type of licensed project has become far more common in the industry. Some of the biggest franchises in gaming now are licensed projects, whether it's Batman, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, The Walking Dead, or Spider-Man. Big licenses are no longer the red flag for consumers that they were several decades ago.

"At that point in time, the games industry was looked at more as a hobby for people, in my opinion," Caplan said. "And I think producers, directors, and creators looked at the game industry much differently then. 'Oh, it's another area where perhaps kids are going to engage my characters.' But they didn't really see the value of the community back then. I think now everything has been flipped on its side. It's all a continual evolution in terms of where fans went. If you look at the games that are made now, there's a lot more critical awareness from the consumer; they expect the game to be a great experience."

"The cost of a game back in the '90s is so much less than the cost of a game in the 2000s, when development budgets were going over $10 million, over $20 million."

Caplan has seen those attitudes change every step of the way. After a few years at Fox, he jumped to Sony Pictures Entertainment where he helped produce games for big names like Spider-Man, Ghostbusters, and The Smurfs. At the end of his two-decade stint there, Caplan was senior vice president of global consumer products and in charge of a lot more than just game licensing.

However, that broader remit also took him away from working with game developers and publishers, an area he personally enjoyed that was also where he felt he had the most to offer. So a couple years ago, he left to join BDLabs. It bills itself as a global entertainment business development company, but in plainer terms, much of its work involves connecting IP owners and licensing partners, whether it be helping Guns of Boom developer Game Insight find IPs to use in their games or working with toy company Spin Master to bring one of their core brands to games.

So what happened to make licensed games better? A few things, not all of them universally regarded as positive developments.

"As the console business evolved, the cost of development increased, and the risk factor grew," Caplan said. "The cost of a game back in the '90s is so much less than the cost of a game in the 2000s, when development budgets were going over $10 million, over $20 million... Licenses became a little too risky on the console side to pour in all the development and marketing dollars."

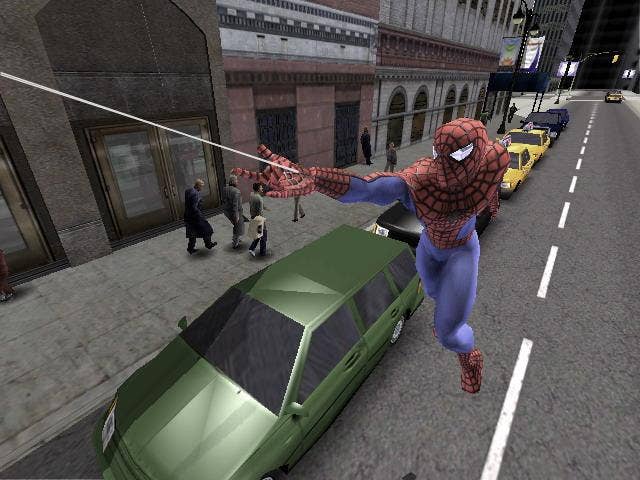

With a larger buy-in required, the quantity of licensed projects dropped. But at the same time, there were just enough big licensed games that released and justified those spiralling budgets that film and TV creators began to see games as a valuable commodity worth their time and investment. Caplan worked on a few of those himself, like the Spider-Man games based on the trilogy of moves starring Tobey Maguire as the wall-crawler. Right from the beginning with the adaptation of the 2002 film, Caplan was struck by the way the filmmakers wanted to be involved in the process.

"We had countless roundtable meetings, not only with the game producers but with the film director Sam Raimi, producers of the film Avi Arad, Kevin Feige, and others to pitch the concept," Caplan said.

It was clear the creatives on the film side were taking the game project seriously. Raimi needed to be persuaded to allow the game to go beyond the film's cast of characters and bring in other Spider-Man villains like Vulture, Scorpion, and the Shocker. (He did.) The developers were invited to the set during the filming of some key scenes so they could get a feeling for the film's temperament and tone. Even the on-camera talent got involved, as Tobey Maguire came in for a voice-over session and treated it like more than a contractual obligation.

"He was totally into it," Caplan said. "It was totally natural for him to act as Spider-Man in a sound studio with some direction from us and the producers. That gave me the sense that yeah, talent and directors do want to be involved. Because they care about the output... I saw the potential with Spider-Man. I saw the potential of a Sam Raimi saying, 'Yeah, I know this game industry. I know the digital lens that games are coming to in terms of quality.'"

The willingness of top creative talent to get involved with games grew from there. For 2009's Ghostbusters: The Video Game, Caplan helped get the cast of the original on board. With the film franchise long-since dormant at the time, Dan Akroyd, Bill Murray, Harold Ramis, Ernie Hudson, and Annie Potts all reprised their roles from the first two Ghostbusters for a game that would essentially serve as a third movie. They even got the blessing of original director Ivan Reitman.

"From what I recall, it was really Dan Akroyd who pushed the rest of the group to get involved," Caplan said. "The producers of the game decided they were only going to do the game if they had the talent, so what I had to do was go meet with the talent agents to convince them it was an opportunistic thing for the folks as well. We had to go back to the agents and convince them we had this really great opportunity to bring the band back together. 'We know it's not a movie, it's been years since there was a movie, but we can do it in a game and we can do it right.'"

Akroyd, Murray, and Ramis all contributed to the storyline or wrote the scripts for the game, a level of participation that Caplan said "carried a lot more weight than just a licensor saying, 'Hey just go make a game and we'll see you in 18 months.'"

"The producers of [Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy] have a very obvious passion for what their product is in the end...They pushed us and the developers to really make sure every element of the game matched specifically what happened on the show"

In fact, the big-name film talent turned out to be more committed to the project than the publisher. The Ghostbusters game was originally a Sierra Entertainment project, but when Sierra was subsumed in the 2008 Activision Blizzard merger, its new parent company dropped the game. (Atari scooped it up, along with another abandoned licensed title in Chronicles of Riddick: Assault on Dark Athena, and published them both in 2009.)

Not every big license Caplan worked with needed to have an awakening about the importance of its gaming tie-ins. The first IP holders he ever worked with that fully understood the possibilities of gaming adaptations were the people behind Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy.

"The producers of the shows have a very obvious passion for what their product is in the end, and I have to give them a lot of credit," Caplan said. "They pushed us and the developers to really make sure every element of the game matched specifically what happened on the show, in terms of the cadence of the questions, the answers, the puzzles for both Wheel and Jeopardy. And it just really made for a better product, in my opinion."

The willingness of creatives to get involved in games has certainly been a sea change in the field of licensed games, but it's far from the only one. All of the trends that regularly re-shape the games industry at large are obviously impacting licensed projects as well. And that's changing the way developers and IP holders deal with one another.

"The proliferation of all these new platforms has given the opportunity for more developers to come into the mix and create their own IPs, or for publishers to invest internally with their own IPs," Caplan explained. "It's a bigger ocean of opportunities, yet it's a more finite group of companies that actually feel like they need a license to move their business forward... There are a ton of IPs but companies are a lot more selective in this day and age due to developing and owning their own a little bit more."