What lessons can be learnt from Voodoo's action against Rollic? | Opinion

Harbottle & Lewis' Kostya Lobov looks at what the casual games giant's victory means for fighting clones

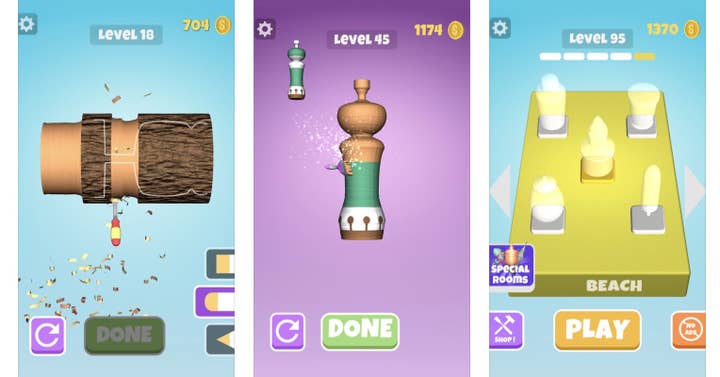

Voodoo, the French developer and publisher of casual games, was recently successful in a legal action against Rollic over features of a game called Wood Shop, a mobile wood-carving simulator.

The original version of Rollic's game actually pre-dated Voodoo's Woodturning, but this dispute was about a subsequent update released by Rollic adding certain features, such as the use of stencils for carving each piece of wood, and specific phases of gameplay -- which Voodoo argued were copied from its game.

One of the reasons why this decision is interesting is that it suggests that the addition of incremental game features could be protectable, even in the context of a game whose concept is similar to an existing title, and where those features may not have the benefit of copyright protection because they lack originality. In that sense, it is a decision to be welcomed by studios whose games suffer at the hands of clones.

With an increasingly saturated casual mobile games market, it is almost surprising that cases like this do not happen more often

However, whilst some press outlets have hailed this as a landmark decision which will have a larger impact on the games industry, it is important to bear a couple of points in mind.

Firstly, each country has its own intellectual property laws, and its courts have their own views on how those laws should be applied. Whilst there are similarities, the positions are not always the same from country to country -- even within the EU, where some laws are 'harmonised' to an extent to promote consistency.

This is a first instance decision of a French court, decided under the French law principles of droit d'auteur and concurrence déloyale et parasitaire -- also known as, unfair competition and parasitism. These are conceptually similar to 'copyright' and 'unfair competition' laws in other countries, but they are not identical and have their own nuances. For example, the way that a French court decides who is the owner of a droit d'auteur differs from how an English court would decide who owns the copyright in a work. There is therefore no guarantee that a court in the UK, US or Germany would necessarily reach the same conclusion, or reach it in the same way.

The geographical scope of the remedies awarded by the court to Voodoo -- including the order stopping Rollic from distributing the version of the game with the features found to be infringing -- is limited to France. This explains the relatively low level of damages awarded by the French court -- just €125,000.

The replication of gameplay features, even those which may seem basic or inherently linked to the type of game in question, can clearly pose a risk

It also means that, in theory, Rollic is free to continue distributing its game everywhere else, provided the app stores are willing to keep it listed. Of course, in practice, there are commercial reasons why a studio might choose not to do that -- for example, to limit its exposure to financial penalties, especially if it thinks that courts in other countries would likely to reach the same decision.

These points are not intended to pour cold water on the Paris court's decision, but to highlight that we may need to wait and see how the dispute between these two competitors pans out, and how/whether a similar approach is adopted by the courts of other countries, before drawing any wider conclusions.

Ultimately, despite their differences, the courts of most commercially significant countries have the tools necessary to deal with instances of copying at their disposal. With an increasingly saturated casual mobile games market, it is almost surprising that cases like this do not happen more often. In fact, actions of this sort are relatively rare and, when they do happen, many of them are settled and do not proceed to a trial.

This decision comes at a time when the spectrum of what is protectable by copyright is being expanded by the EU Court of Justice, with last year's decision in a case called Cofemel potentially opening the door to innovative arguments that original game features (or games as a whole) can be protected as 'copyright works' in their own right, without the need to jump through any additional legal hoops.

It will be interesting to see if this decision, together with the legal developments happening at the EU level, will embolden other studios to try similar actions, either in France or elsewhere. In the meantime, a practical takeaway for studios is that the replication of gameplay features, even those which may seem basic or inherently linked to the type of game in question, can clearly pose a risk.

Where possible, the safest approach is to have some evidence which can be used to show that gameplay features were conceived independently, without reference to any existing games or material. For example, by a designer who was given a general brief, but whose mind was not polluted by knowledge of existing titles.

Kostyantyn Lobov is a partner in the video games group at Harbottle & Lewis, which has been advising the games industry since the days of the 8-bit console.