Weird West's narrative designer seeks a world without cutscenes

Industry newcomer Lucas Loredo shares his inspirations and how he wants to change the way games tell stories

Storytelling in video games comes in many forms, whether it's in-game dialogue, environmental details, or even info dumps of lore via found documents and audio logs. Cinematic cutscenes have been a firm staple of delivering story beats and important plot moments, but some games writers are keen to find alternatives.

One such writer is Lucas Loredo, narrative designer on Weird West -- an action RPG with qualities of an immersive sim, set in a Wild West frontier that borders on dark fantasy.

Though plot specifics are under wraps, Weird West's storytelling seems to favor unique player experiences over traditional cutscenes. With this dynamic approach, the real story comes from how the game reacts to player input.

"In my ideal world, honestly, there would be no cutscenes -- which is a weird thing to say as a writer," says Loredo. "I think they can be used effectively... but do they even belong in this medium at all?"

To Loredo, taking control from the player creates experiences that "are not the fullest realization of the medium." What keeps Loredo excited is the search for and continued refinement of an alternative source of storytelling in games that feels more organic.

"What does it look like to tell a super story-driven game without cutscenes?" says Loredo. "How would you make The Last of Us Part II without cutscenes? I don't really know but I'm curious to be a part of figuring it out."

Loredo's personal journey with games began in the varied worlds of Nintendo. Super Mario World, Donkey Kong, and (after resisting its initial popularity and exhausting Blockbuster's other rentals) The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time were major influences on him.

"There's a level of whimsy, warmheartedness and playfulness that really resonates with me," he says, linking his experience of Zelda to his favorite Miyazaki and Pixar films. "I remember running around Kokiri Forest and being like, 'Oh my god, what is this? I've never played anything like this before.'"

"Cutscenes can be used effectively... but do they even belong in this medium at all?"

But when it came to realizing that game writing and design was even a possible career, his strongest touchstone belongs to Metroid Prime -- another game that primarily tells its story without cutscenes (the vast majority being used to introduce bosses). Instead, players piece together what is happening by scanning enemy logs, ancient texts and more.

"I remember playing that in middle schooland being so swept up in the environments, the lore of the Chozo, and the music," says Loredo. "I can still play 'Phendrana Drifts' in my head whenever I want to -- it's amazing!"

His initial awe turned to curiosity, leading him to find the development team working in his hometown of Austin, Texas: "I remember looking up Retro Studios' job board when I was 13 years old to see if they had a janitorial job or something I could do -- just so I could be in the building where they were making games."

Loredo's ultimate path into games writing didn't take him through Retro or any custodial work in major office parks -- he instead joined the ranks of Raphaël Colantonio and Julien Roby, ex-creative director and ex-executive producer at Arkane Studios respectively, on a worldwide team at Weird West developer Wolfeye Studios as a narrative designer. But before he could spin tales about hapless cowboys and ferocious monsters, Loredo needed to hone his storytelling on a smaller but more intimate stage.

Loredo admits he "hated reading even as a kid" until a high school teacher introduced him to influential texts like J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye and Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried. Subsequent writing assignments sparked a creative passion for short fiction that came at a critical point in Loredo's life. His mother passed away when he was young, and writing gave him a vehicle to channel his grief.

"I think a lot of my first writing had to do with me wanting to communicate with my dad about specific things," says Loredo. "He would take the time to sit and read, and I felt like I had his full undivided attention... there was a draw to write stories that my dad would read to help him better understand what I was going through."

"Story is friction and resolution, a chain of events that lead somewhere. All content between A and B creates the story, and the player needs to see something that's enticing"

Loredo would insert stand-ins for himself and other figures of his life into fiction, such as Danny, a recurring character who lost one parent and was struggling to bond with the survivor, or Leo, a father reentering the dating world after becoming a widower.

"It was like my Marvel universe of pain and death," jokes Loredo. But it's one that helped him process complex emotions while simultaneously creating new, believable people and places.

Loredo's short fiction earned him acceptance into the University of Texas' Michener Center for Writers, a competitive MFA program that altered the trajectory of his career in surprising ways. Loredo enrolled in a course on game writing taught by Susan O'Connor -- a venerable figure whose portfolio includes BioShock, Far Cry 2, and the 2013 Tomb Raider reboot -- and the two of them shared an instant connection.

"She's so warm and so exciting," says Loredo. "She and I just vibed with each other so well and the way she was talking about game writing in this class was fascinating to me and really 'chewy'."

O'Connor's course made Loredo stretch his skills, including a "game about freestyle rap battling sort of in the vain of Pokémon." But it wasn't until six months after graduation, when Loredo was working the blenders at a local smoothie bar, that O'Connor reached out with an opportunity paired with a strong recommendation for him to join Wolfeye Studios on their introductory effort.

With its branching pathways and dense scenery, Weird West has proved a welcome challenge for Loredo. In order to adapt from traditional fiction writing to fleshing out the narrative of a video game, Loredo had to rethink the fundamentals.

First, the assumption that writing game scripts follows the mode of your typical film screenplays -- as cutscenes tend to do -- when in truth "it's closer to creating an immersive theater experience." Loredo's writing needs to account for constants and variables influenced by the player, which means emphasis is placed on environmental storytelling over dialogue.

"As a narrative designer, I need to engender spaces with a sense of mystery so compelling that a player can't help but go investigate. If I can do that, they will play for 100 hours"

"The strongest tool I have is imagining environments the player gets to move through in order to communicate to my level designer what the stories of these spaces could be -- the way the scene is decorated and how the NPCs are moving about the space, for example," he says.

For Loredo, narrative design is "the ultimate playground" for writers like him who are "interested in expressing themselves not only through words but also through ideas, objects, sets, and moods."

"[This kind of writing] is so much more vast than [prose] fiction," he continues. "It's sort of like you have a billion toys to play with."

When looking for inspiration in the games space, Loredo lands on two dramatically different examples of storytelling: "If you think of a game like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, there's this story that happens on the critical path... but when I think about my playthrough, that's not even the thing I remember most. I remember the gameplay mechanics and how they interact with each other to create a story that was unique to me."

Features like rock-climbing, paragliding, the elemental and physics system, and the ability to customize the maps with pins that mark points of interest all amount to a personalized story -- none of which is conveyed in the game's (brief) cutscenes.

"Story is friction and resolution," says Loredo. "It's a chain of events that hopefully lead somewhere. There's all this content between A and B that creates the story and the player needs to be able to see something that's enticing. I need to make sure that between point A and B that there will be stuff that creates conflict. As long as this space is filled with nuggets of challenge, of intrigue, that it's dense enough...no matter where A is and no matter where B is, it's going to be interesting."

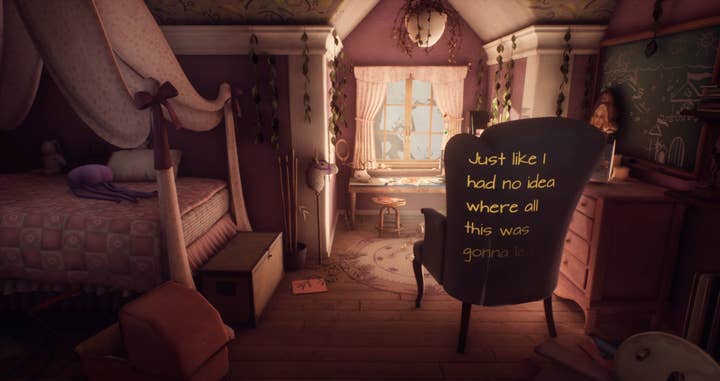

Giant Sparrow's What Remains of Edith Finch employs storytelling techniques that are authored and intentional, comparatively restricting action from the player and instead asking them to be immersed in the fiction and level design with minimal control. To Loredo, it's a "much more contained experience with far fewer verbs" compared to the Hylian adventure, but one that still finds its narrative voice in its own unique way.

"How would you make The Last of Us Part II without cutscenes? I don't really know but I'm curious to be a part of figuring it out"

"I was so taken by the way the narration comes in and pops up as text on the screen," says Loredo. "The letters themselves are 3D objects in the world that you can push and move around."

Additionally, the game world itself -- a family home bursting at the seams with a folktale "maximalism to the nth degree" akin to Lemony Snicket -- asserts itself as an integral part of the gameplay by asking the player to perform light detective work.

"Unraveling the story is gamified," says Loredo. "Every square inch of that space, the photographs, the writings, the music box... [Giant Sparrow] packed it full of great interactivity."

On the other side of this focused feedback loop, the story provides rewarding closure to the player.

"The story nuggets are really well written so I feel motivated," says Loredo, likening this structure to the combat and loot system of Diablo.

Looking forward, Loredo is interested in how game mechanics can help elicit a story without the interruption from cutscenes. And for Weird West, Loredo wants players to feel like their time is respected with an effective, immersive world.

"What I need to continue working on as a narrative designer is basically engendering spaces with a sense of mystery that's so compelling that a player can't help but go investigate," Loredo says. "If I can do that in a game, then the player will play 100 hours."