“In the past, YouTubers were very problematic... Suddenly they became our allies"

David Cage and Josef Fares on how streaming can benefit storytellers, and the "serious problem with people not even finishing our games"

Creators of narrative-driven games face many challenges when it comes to convincing players to buy, play and finish their stories. However, at the Gamelab conference last month, Quantic Dream's David Cage and Hazelight Studios' Josef Fares told the audience that even platforms like YouTube and Twitch are now working to their advantage.

At Gamelab in Barcelona, Gamesbeat's Dean Takahashi conducted an onstage interview with two of the industry's most recognised storytellers: David Cage, whose work with Quantic Dream includes Heavy Rain and Detroit: Become Human, and Josef Fares, who made Brothers: A Tale of Two Suns with Stabreeze before founding Hazelight to make A Way Out.

However, while both have made commercially successful games, a media landscape increasingly dominated by YouTube Let's Plays and Twitch streams poses a significant threat to any studio that sells games based on story. As many developers in the past have stated, too many people will just watch the game on video instead of paying to experience it for themselves.

"In the past, YouTubers were very problematic for us... With Detroit, the opposite happened"

David Cage

As Cage explained, though, it is now vital to provide a narrative experience that cannot be easily captured in a Let's Play or a livestream -- such as the myriad branches to the story of Detroit: Become Human.

"We can never count exactly how many endings there were to Detroit. It was not about the endings; it was about having a different path, leading to different endings," he said. "The journey itself is different, and different characters can be present, or be dead, or make different moral choices and be in different situations by the end."

The emergence of YouTube as a platform for gaming videos had caused issues for Quantic Dream in the past, Cage said. However, the solution was simply to focus on the kind of situations the players face in its games; a choice where only 10% of players choose one of the two options is not enough, for example, because "the dilemma is not really there." In a Quantic Dream game, every choice should split the audience 70/30 minimum, and ideally be 50/50.

"What we realised is the very positive impact this had on the community, and on the sales of the game," Cage continued. "In the past, YouTubers were very problematic for us, because players were watching those videos thinking, 'Okay, I've got the story, I don't need to play the game, I know what it's about.'

"With Detroit, the opposite happened. They were showing one walkthrough, but they couldn't show all of the things that happened in all of the branches. Players watching thought, 'I wish he'd done this'... Suddenly they became our allies, and they helped us to promote the game."

"A Way Out was the number one game on Twitch. I thought, 'Oh sh*t, we're f**ked'"

A Way Out is a more linear game, but Fares noted that video platforms had also boosted its sales. Rather than a story with dozens of possible paths, Hazelight's debut had innovative co-operative gameplay, and that gave it an appeal that was not satisfied simply by watching.

"I remember when it came out, and A Way Out -- which was still an indie title -- was the number one game on Twitch. I thought, 'Oh shit, we're fucked.' But then it sold really well, because people saw it and wanted to play it. In A Way Out's case, it was because they wanted to experience it with someone who hadn't seen it on Twitch."

The struggle to create a narrative game that people will buy and play rather than simply watch online is just one hurdle. The next is to fight against the tendency among players to abandon games before the story is finished, despite those same players often using the length of the experiences created by Hazelight and Quantic Dream as a reason not to make that initial purchase.

The logic is frustratingly contradictory. Big publishers are forever increasing the scope of AAA blockbusters to attract gamers, which in turn makes games like Detroit or A Way Out a harder sell. But those huge AAA games are only finished by a minority of players, making a false economy of the extra value they claim to provide.

"People say to me, 'Oh man, A Way Out, 50% of people finished your game.' I'm supposed to be happy about this? Are you fucking crazy?" Fares said. "It's like having a movie in a cinema and half the people walk out. We have a serious problem with people not even finishing our games, and still people complain about replayability."

Cage agreed, adding that between 25% and 30% of people actually finish a game they start, but that proportion was 78% for Heavy Rain and a similar level for Detroit.

"It's the story," Cage said. "People want to know what's going to happen next, and a story can achieve this for you. What's interesting on Detroit is that we managed to make people replay, so they could see all of the different branches -- which is quite rare in a narrative game. We achieved this because we showed all of the branches and the variations of the story."

"Developers too many times ask: 'What do the players want?' I love my players, but they should also respect me and trust me"

Josef Fares

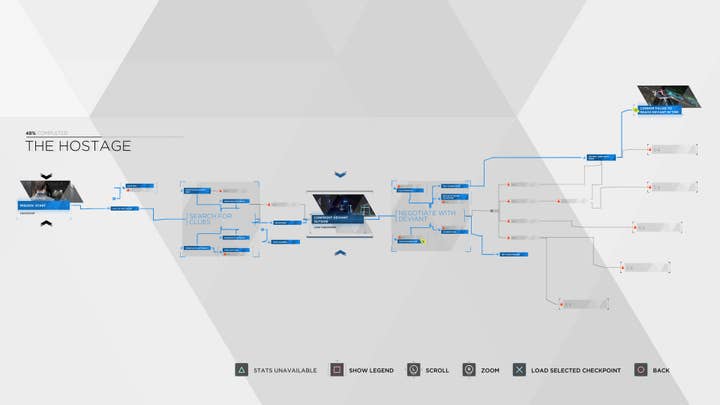

In Detroit, players have access to a "flowchart" that shows not just their own choices, but also the roads not taken. Quantic Dream wanted players to "know all of the things that go on behind the curtain," where in Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls those alternate paths remained hidden.

"Maybe that was not a good decision," Cage said. "Maybe hiding everything from the player is not a good thing. Detroit was a better compromise, because it was about showing part of what you missed, and that played a major role in the success of the game."

Cage added: "Branches [that nobody ever sees] don't exist. We're trying to make sure that at least 30% of people see all of the branches, and that is pretty much the statistic that we had."

This is the very quality that has switched Twitch and YouTube from existential threats to conduits for more sales and promotion. It is also an example of Quantic Dream giving its players something new -- something that, had they been asked, might have rejected in favour of the more familiar methods of previous games.

Exactly how much input players should have in the creative process has been a hot topic ever since Bioware changed the ending of Mass Effect 3 over a player petition. However, both Fares and Cage were clear about the value of the developer staying true to their vision for a given project.

"I do think that developers too many times ask, 'What do the players want?'" Fares said. "I love my players, but they should also respect me and trust me and the vision I'm trying to create. From a story perspective, I think it's important to have a clear vision and goal, and stick with it and trust it.

"I'm not as experienced as David, but I know from the two games I've done before now -- and I'm working on a third -- many of the decisions, if I had based them on what the community would say or what the people thought they wanted to play, those two games would not have been possible. I trust myself more."

Cage added: "There are different ways you can approach your job as a creative person. Either you receive a marketing brief, telling you all the boxes you need to tick, because it was successful last year... That's one way of doing games, and I respect that.

"But I think if you want to be a creative person in this industry, you have to think about what people will like four years from now -- not what they liked last year. It is about taking risks, it is about going where people maybe don't want you to go. Maybe they don't believe in what you're doing, and that's fine -- because I'm willing to take the risk."

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner of Gamelab 2019. We attended the event with assistance from the organiser.