V&A Museum: Video games are approaching a cultural tipping point

Curator Marie Foulston discusses how the industry can help a wider range of people understand our full impact and potential, and get them to look beyond the blockbusters

The wider world seems to have tunnel vision when it comes to video games, particularly when compared to other forms of entertainment.

When it comes to film, people are often just as aware of the acclaimed, smaller dramas as they are the big, noisy blockbusters like Marvel and Star Wars. And there is plenty of awareness around the world of literature, with your average person on the street able to name both historical classics and more recent bestsellers.

But unless they partake in the hobby itself, there is still a remarkably significant proportion of the populous that believe video games are defined by just Call of Duty, FIFA and Grand Theft Auto - plus family friendly stuff like Mario and Pokémon. There is far less awareness of celebrated independent titles, even BAFTA winners What Remains of Edith Finch and Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice.

It's a frustrating state of affairs for anyone in the industry, but it is one that Marie Foulston, curator at London's famous V&A museum, believes is coming to an end.

"That literacy, knowledge and respect of the full range of games is something [we're gaining]," she tells GamesIndustry.biz. "I think we're at the tipping point, where it's beginning to happen.

"A game like Journey - yes, it's a smaller, independent title and not as big as some of the blockbusters - but people are beginning to understand the appeal of titles like this. When you look at the work the British Library is undertaking, the Wellcome Trust, the Smithsonian, MOMA [Museum of Modern Art]... Through cultural spaces, that's where we have the ability to show the broader range of games. Games communities and people that play games understand those and know how they work."

Foulston and her colleague Kristian Volsing, research curator, are hoping to push this further with their newly announced exhibition, Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt. Taking place at the V&A from September, this five-month initiative will showcase the work that goes into a wide variety of games, from AAA titles to indie sensations, as well as the cultures that develop around them.

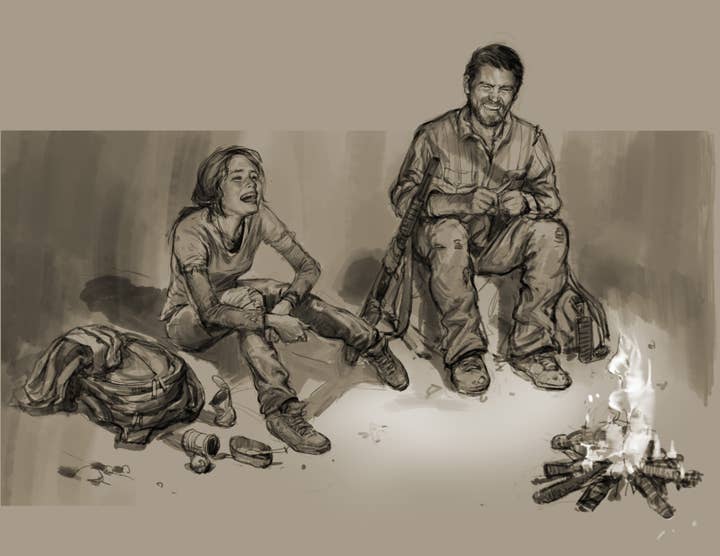

Foulston tells us that while the larger titles featured, like Naughty Dog's The Last of Us and Nintendo's Splatoon, are likely to turn heads, the exhibition is also designed to raise awareness of those smaller games - "especially for audiences who aren't as literate as those of us who are familiar with those titles."

"Institutions such as museums can play an important part in educating people on what's so amazing about games"

She continues: "We get to show them the full range of video games, that video games are more than perhaps what their expectations, stereotypes and perceptions are. Institutions such as museums can play an important part in communicating that and educating people on what's so amazing about games and the true potential of this medium."

This sentiment is perhaps typified by the Disrupt section, which explores how video games can participate in serious social and political debates. Examples include Molleindustria's Phone Story, a satirical mobile title that explores the negative impact smartphone production has on the world and the third-world workers sourcing materials for their components, and How Do You Do It?, a 2014 indie game by Nina Freeman that explores the notion of sexuality through the eyes of an 11-year-old girl.

In her opening address at the exhibition's announcement earlier this month, Foulston said there seem to be preconceived notions of what topics video games should and shouldn't cover, but the V&A hopes to, "show how advanced and how nuanced the conversations have been within games communities, particularly among the people creating them."

"People who aren't familiar with games are probably only familiar with the same debates that still keep getting churned around - they don't know there's actually so much more going on," she says. "There is so much complexity, so much discussion about what video games can be. That's what we want to show people, to elevate those voices and provide a place for that."

However, she stresses that this is not about defining the remit of games - regardless of how broad we might deem that to be. Instead, the goal is to encourage attendees to make that definition themselves.

"This exhibition is not providing answers," Foulston explains. "The aim to provoke conversation, provoke debate and discussion - and to do that, we're showing works that have sparked debate and discussion. We're showing people a range of those discussions and some of the opinions, so that people can come in, see that work and debate for themselves. It's not for us to tell you what subjects games can and can't cover, it's for you to think about and to reflect on those moments."

"There is so much complexity, so much discussion about what video games can be. That's what we want to show people"

The access the V&A has secured for the exhibition is impressive. Not only have they managed to get design materials from various indies, but also gaming powerhouses such as Naughty Dog and Nintendo. In addition to videos of the final product, attendees can look forward to original character sketches and other forms of artwork.

The experience of gathering these materials has given Foulston a "newfound love and respect for those works" - although she is reluctant to pick a favourite exhibit.

Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt is also interesting in that it focuses on a much more recent period. Past video games exhibitions, such as the Barbican's Game On, have often concentrated on the history and evolution of the medium, dating right back to its origins in Pong. But the V&A is selecting pieces from the mid-2000s onwards - although Foulston warns that her team "can not and will not" showcase the entirety of games design from the past two decades.

"This is not a canon," she says. "This is not everything, but we hope this is the beginning of other exhibitions, both in the V&A and elsewhere, that take on this subject, that look at different studios and their methods. We're hoping it forms the foundations of a new curatorial language for video games and the way they can be displayed."

"It's not for us to tell you what subjects games can and can't cover, it's for you to think about and to reflect on those moments"

She continues: "I think when we look back in future at the mid-2000s to the present day, not just at video games but across design as a whole, that there have been huge changes that have been radically impacted by technological catalysts like broadband, smartphones, social media. That has changed the way we live, and has quite immediately affected video game design in a visible way - and an amazing way sometimes."

It's not just about demonstrating the breadth of video games, but the breadth of their audience. More than two billion people play games, even though a significant portion of these - the Candy Crush and Clash of Clans players - probably don't even consider themselves part of the hobby, despite pouring in as many hours as your hardcore enthusiast.

As such, the V&A is determined to show as broad a range of games as possible. Alongside titles like The Last of Us and Splatoon are exhibits around the League of Legends World Championships, the Minecraft community trying to recreate Game of Thrones' Westeros continent, and the arcade fans building their own cabinets.

"Video game players aren't some homogenous audience that all love the same things," says Foulston. "Everybody has their own specialisms in different areas and that's what we wanted to represent with this exhibition."

"Big AAA studios and their design processes can often look quite inpenetrable, so showing some of the design objects from within that process can break it down"

Placing video games so prominently in such a renowned institution can also only help to validate the industry, and potentially encourage those interested in art and design to pursue a career developing games. Was that a consideration for Foulston and Volsing as they curated this event?

"I'd love for this exhibition to inspire people to create," she says. "There are a range of works that come from big AAA studios and their design processes can often look quite inpenetrable, so showing some of the design objects and artefacts from within that process can begin to break it down and make it understood.

"It's also important that we have the work of these solo and independent artists, because it shows that people don't necessarily have to aim that high. They can just create smaller, very personal works with no constraints about what subjects, areas or ways in which you want to create.

"It would be really fantastic if people came to this exhibition, saw that creation and then be able to see themselves within that."

To that end, the V&A is also looking for a games designer, developer or artist to join the team in the institution's new video games residency program, building on the work accomplished when Sophia George was game designer in residence.

"It's amazing the legacy and the impact that had," says Foulston. "To this day, when I introduce myself to people and say I work at the V&A and I work across video games, they're like, 'oh, you're Sophia George'. So you can see the impact that had, and that was something we wanted to recreate. We wanted to build on the awesome work she had done, but also the other residencies that other people had undertaken here.

"We're looking for an artist, designer or practitioner whose creative work will be inspired by and feed into the themes we cover in the exhibition. That person will almost be a living embodiment of everything the exhibition is looking into."