Unease over Unity’s future threatens an industry pillar | Opinion

Platforms like Unity and Unreal are the backbone of the industry – but some developers who have invested heavily in Unity are jittery over the company’s direction

What are the most important companies in the games industry? The answer depends heavily on your interpretation of the question.

One might be tempted to look to the companies with the largest market capitalisation or the largest sales numbers, or perhaps those with the largest active user numbers. Certainly, you could also look to the hardware companies whose innovations underpin the industry’s efforts – the NVIDIAs and AMDs of the world, or perhaps to a lesser extent, the console platform holders.

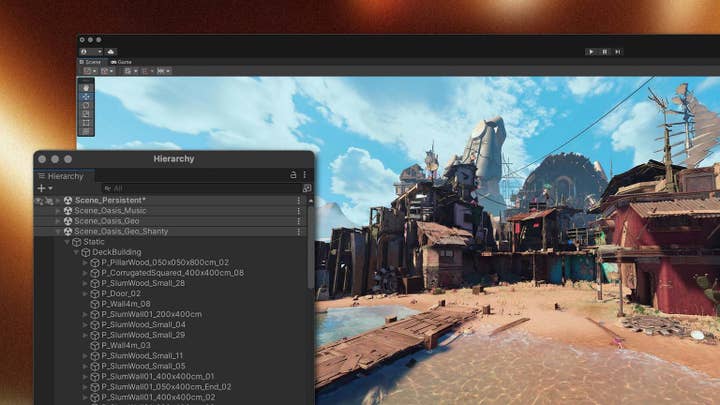

One other category of company, however, stands out as being vitally important even if not always all that high profile, and that’s the companies which provide the software tools and platforms upon which almost all modern games are now built. In essence, there are two key players here (along with an interesting ecosystem of other players who serve more specific niches) – Epic Games’ Unreal Engine, and Unity’s eponymous engine.

Each of these is a game development platform that’s available across a dizzying array of hardware platforms, and offers a set of tools that solve problems all along the production process – many of which have found applications far outside the games industry itself. Without Unity and Unreal, it’s no exaggeration to say that much of what the games industry does would be impossible; developers would be forced to reinvent all sorts of wheels over and over again, vastly amplifying the cost and pain of game development.

These platforms, the most recent evolution of what was once termed "middleware" (a term that was somewhat disparaging, until it became clear that it was about the only approach that made sense for commercial game development, at which point the notion of a home-grown game engine was the thing that started to seem heavily suspect instead), underlie the efforts of almost all game creators and have been instrumental in the democratisation of the medium – opening it up to creatives like small indie teams for whom the technical barriers to game development would otherwise have been dizzyingly high.

Without Unity and Unreal, it’s no exaggeration to say that much of what the games industry does would be impossible; developers would be forced to reinvent all sorts of wheels over and over again, vastly amplifying the cost and pain of game development

Consequently, game developers care about what’s happening to these platforms – they care very, very deeply, in fact. Lately, that care has been turning into outright anxiety regarding Unity in particular. The company had a pretty successful IPO a little under two years ago, valuing it at almost $14 billion – a value which soared in subsequent months as investors liked what they saw from the firm.

For creators who rely heavily on Unity’s platform and technologies to enable their development processes, that seemed like a guarantee of stability and future support for this crucially important piece of industry infrastructure – but in recent months, the whole question of Unity’s future direction seems to have been pulled into question, and the company’s top executives haven’t done a great job of reassuring nervous developers that their investments in the platform are secure.

There have been various twists and turns in this drama – most minor, some less so – but the most recent is Unity’s decision to reject a takeover / merger bid from AppLovin, a very acquisitive mobile monetisation technology company. AppLovin’s offer for Unity would have in effect been a takeover, albeit one that left John Riccitiello as CEO of the new combined company, meaning that Unity’s engine and platform would have become subject to the whims of a company whose previous acquisitions and track record suggest a rather narrow view of game commerce and monetisation.

Unity developers will be relieved that the deal didn’t go through – but will remain concerned about the other major commercial deal Unity is engaged in at the moment, namely the acquisition of ironSource, a similar but much smaller mobile monetisation and analytics technology firm. That deal will see Unity staying far more in control of its own destiny as a company, but remains deeply controversial with Unity’s customers. It’s also not much of a hit with the company’s shareholders: the company’s stock, having bumped along comfortably at a nice multiple of its IPO price since late 2020, has been falling since last November and dropped precipitously to well below that psychologically vital price point back in April.

As Unity CEO, Riccitiello has found himself as a magnet for criticism – which came to a crescendo a few weeks ago when he ran his mouth in an interview with PocketGamer.biz, describing developers who don’t engage with analytic approaches to monetisation strategy from early in the development process as "fucking idiots."

Riccitiello insisted that his comments were taken out of context; the context, honestly, explained his thoughts more clearly but still wasn’t much better. His lengthy apology a few days later hit many of the right notes, but still left a sour taste in many developers’ mouths for its seeming insinuation that his original sentiments still applied to any developer who wants to make a living from games, as distinct from those merely creating as an artistic, non-commercial endeavour.

There probably wasn’t anything Riccitiello could have said to actually make Unity’s developers happy in that moment, though, because much of the anger that met his statements had been building up for months and months among Unity users. The ironSource deal is controversial precisely because some Unity users view it as a crystallisation of problems they’ve been having with the company for some time.

They perceive the Unity platform itself as being somewhat neglected in terms of updates and support while the company instead chases after the notion of being a major player in app monetisation and analytics, or in the metaverse, whatever the hell that actually turns out to be. Sure, a company with Unity’s scale can do more than one thing at once; but concern about an attempted and possibly misguided pivot that distracts the company’s management from supporting and improving its core product is exactly the kind of thing that makes developers very, very nervous.

Unity would be far from the first technology company to shoot itself in the foot by neglecting its core product in favour of pursuing pie in the sky notions

Developers who use Unity have, after all, invested heavily in this platform; they have not only built products on it, they have built their own personal skillsets upon it, and if the Unity platform goes into decline it could harm their businesses and careers very badly. Moreover, there’s plenty of precedent for even such a popular and successful platform to lose its edge.

Unity would be far from the first technology company to shoot itself in the foot by neglecting its core product, the thing in which it’s meant to be world-class and industry-leading, in favour of pursuing pie in the sky notions – often framed as diversification, but really representing a change of direction that the company’s executives fail to recognise is a pivot away from existing clients and users, as much as a pivot towards some bright new sunlit uplands.

This isn’t to say that there’s anything intrinsically bad about a platform like Unity having monetisation tools such as analytics suites as part of its offering. That’s a good idea in principle; many developers, especially of mobile titles, will find significant benefit in being able to use professional tools to test and analyse the effects of different monetisation strategies, user journeys, and so on.

This stuff isn’t all black magic and cynical psychology; a majority of developers, I think, would see the benefit of being able to make properly researched, data-driven decisions about how to monetise their games, whether that’s through microtransactions, subscriptions, or even just data showing the most effective design for an app page where users pay to upgrade from a demo to the full version of a game. If Unity can offer that as part of its platform, it will be a welcome option for many.

The problem arises if that tail – monetisation technology – starts wagging the dog – the gaming technology platform itself. That’s what Unity stakeholders, be they clients, shareholders, or even some employees, seem worried about; that the company’s focus may have gone too far down this rabbit hole, leaving a perception (if not a reality – that’s harder to assess) of neglect for the core product, the platform itself.

Riccitiello’s track record, while generally excellent, raises some specific red flags in this regard; he is best known, of course, for his lengthy tenure as CEO of Electronic Arts, which was largely seen as successful from a management perspective, but saw short-sighted decisions being made on monetisation strategy for core games (Mass Effect’s sequels are often cited as a particularly egregious example) which arguably damaged the long-term value and appeal of some of the company’s major IPs.

Short-sightedness is bad at a publisher – it often manifests in prioritising the maximisation of profit from a single instalment in a franchise over the future prospects and value of the franchise overall – but it’s potentially lethal at a technology and platform company that relies almost exclusively on personal investment and goodwill from developers to sustain its business.

That investment of time, effort, and money in the platform creates friction on the way out, meaning that there’ll be a lot of loud complaints before people start voting with their feet and creating a danger that the company underestimates genuine dissatisfaction because the noise vastly outweighs the actual user attrition at first. It also creates enormous friction on the way in, which means that those loud complaints dissuade potential new users, and ensure that clients lost to alternative platforms are vanishingly unlikely to ever return.

Not every developer wants to maximise revenues at the cost of other aspects like reach, brand value, goodwill, or a good old fashioned creative vision – and that’s fine and must be respected

Once the ironSource acquisition completes, Unity will have a relatively narrow window in which to convince everyone – developers, shareholders, and to some extent, itself – that it hasn’t forgotten its core mission and its core product, and that it remains the best option for a developer to choose when starting a major new project, regardless of what kind of monetisation strategy they plan to pursue. That will mean knuckling down to focus on the quality of, and support for, its core platform, and it will mean restraining the patriarchal urge to insist that business daddy knows best about what monetisation strategy developers should pursue with their own products.

Not every developer wants to maximise revenues at the cost of other aspects like reach, brand value, goodwill, or a good old fashioned creative vision – and that’s fine and must be respected. Even developers who do want to make a living from games may have very different approaches to doing so, and it cannot be Unity’s place to dictate otherwise. That’s a lesson the company’s management must internalise, along with the existential importance of showing that their focus on the core platform is relentless – because if an exodus from Unity starts, stemming the bleed may turn out to be entirely impossible.