The Medium And The Message

"I really don't know what I'm going to do to follow all those explosions" - Jonathan Blow

New hardware is only as exciting as the games it supports. If that maxim sounds plausible, Sony's grand unveiling of the PlayStation 4 may have left you with a few misgivings. There was shooting and driving and dragons and Diablo III; a rich seam of familiarity running through the core of an event intended to usher in a new era of interactive entertainment.

But if that's how it felt as a spectator, the developers on-stage seemed to be oblivious. Guerilla Games' Herman Hulse introduced Killzone: Shadow Fall by conjuring the spectre of Cold War Berlin: a society riven with subtle oppression and suffocating paranoia, which, in Guerilla's hands, became a dense, glinting metropolis with a gunfight on every corner. The police-state analogies continued with Sucker Punch Productions' Nate Fox, whose stern evocation of the Orwellian landscape of 21st Century Britain played like a TED Talk on the erosion of civil liberties.

"We all want to feel safe, right?" Fox asked. "It's hard to put your finger on what that sense of security is worth, but it's easy to say what it costs. Right now, there are 4.2 million security cameras distributed all around Great Britain - that is one camera for every 14 citizens. In 2011, the US government seized the personal cellphone records of 1.3 million of its citizens. There are 1200 of us in here today - 4 of us have been monitored."

"Our security comes at a high price: our freedom." A pregnant pause. "Now, imagine how the world would react if a handful of people developed superhuman abilities."

If Fox's speech seemed misplaced as a primer for inFamous: Second Son, it doubles as perfectly good satire. Moments later, that disconnect between intention and execution was skewered by Jonathan Blow, who, taking to the stage to introduce The Witness, seemed to depart from the script entirely: "I really don't know what I'm going to do to follow up all those explosions."

Blow's uncompromising opinions have made him a divisive figure in the games industry, but his comments shouldn't be dismissed out of hand. If Guerilla and Sucker Punch were indeed sincere, and if they can be taken as representatives of AAA games as a whole, then the industry's most prominent developers might just be kidding themselves. Where Herman Hulse sees, "a story about the loss of home," Blow sees a story about ravishing explosions. Now, there's absolutely nothing wrong with the latter, but when the medium is still maturing and violence is its current lingua franca, it's important to be realistic about where things actually stand.

"I kind of wish we were talking about some bigger topics and other issues... There are so many games out there that just aren't even trying"

Jade Raymond to Kotaku

Speaking to Kotaku recently, Jade Raymond described the hidden dangers of this kind of creative self-deception. Raymond is the head of Ubisoft Toronto, the studio currently working on Splinter Cell: Blacklight - a game whose E3 demo featured a sequence (since removed) where the protagonist, Sam Fisher, tortures an enemy by driving a knife into his throat and twisting the blade. The inclusion of such a scene was no doubt justified by the series' grounding in the ruthless shadow-world of espionage and counter-terrorism, but Ubisoft realised it had gone too far.

And Raymond now believes that the most prominent and visible part of the games industry has gone too far in general. In her interview with Kotaku, she recounted the story of a promising 21 year-old designer whose dream job of making video games was sullied by his experiences at the top table. He stepped back, looked at what his effort was ultimately creating, and decided to step away from the industry.

"He's like, 'I really wanted to do this, but now I realise we're stuck in this place.'" Raymond recalled. "I've had a lot of people come, in serious one-on-ones, to talk to me about: 'I'm thinking of leaving the game industry.'

"They don't like the messages. They don't like the idea that every game is a war game, that we're reinforcing this... They spend time thinking, trying to find meaning in the world, and it bothers them."

"I've always been really excited about games. I got into the industry because I saw the potential. But we continue to be stuck in this sort of teenage narrow-band of themes. I kind of wish we were talking about some bigger topics and other issues... There are so many games out there that just aren't even trying."

The disquieting thing about the presentations of Killzone: Shadow Fall and inFamous: Second Son is that they suggest that AAA developers believe they are trying, even succeeding - that the addition of an ornate, earnest narrative will add new meaning to all the bullets, blood and balls of lightning. For Wolfire Games' David Rosen, it's clear that most AAA developers are mired in the same spot on what he sees as a "spectrum of violence." Even within the relatively limited scope of muzzle-flashes and breaking bones, there is a reservoir of untapped potential.

"It's a common perception in mainstream design that people want everything as simple as possible, and as streamlined as possible"

David Rosen, Wolfire Games

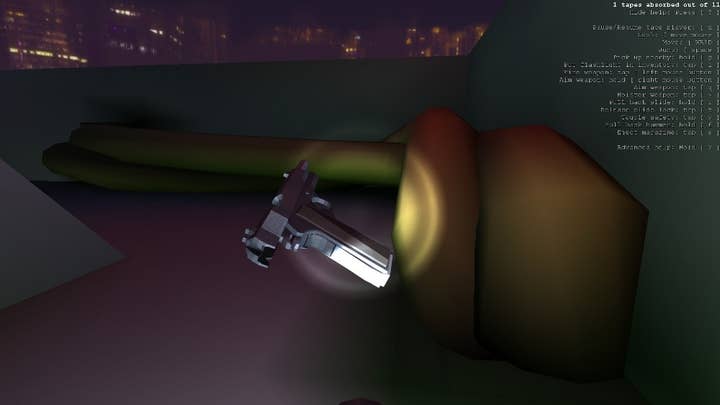

This is illustrated by Wolfire Games' Receiver, a project born out of a game jam devoted to shaking up the first-person shooter - arguably the industry's most popular genre, but also, Rosen believes, its most conservatively designed. "Nothing changes very much from year-to-year, so there's a lot of room to try new things," he says. "I mean, the 2D platformer has been explored very thoroughly at this point, but the FPS is still virgin snow."

Receiver is a bracing response to that stagnation, and probably the most realistic simulation of what it's like to handle an actual fire-arm. Receiver's guns aren't the streamlined death-dealers found in virtually every first-person shooter; rather, they are are complex machines composed of discrete parts, all of which must be manipulated to achieve the usually simple task of making a bullet hit the target. Indeed, the only way to know how many bullets you even have is to pull out the magazine and count. New bullets have to be manually loaded into the magazine one-by-one, and you only have two hands, so you'll need to holster the weapon first.

Receiver exposes one of the most prevalent abstractions in game design. It laughs in the face of marathon kill-streaks and orgiastic head-shots. There is a palpable and enthralling sense of the pressure involved in operating a weapon while enemies bent on your destruction swarm all around you. Death is permanent, and when the player returns everything has changed: the environments and enemy locations are randomly generated, the confusion never lets up.

"[Firing real guns] is really complicated," says Rosen. "It's hard just to load bullets into a magazine. It takes a lot of force and finesse to do that. When you have combat you should have tension - like a fear of failure. Dying and restarting in a randomised world is more punishing than going back to a quick save and doing the same thing all over again.

"It's a common perception in mainstream design that people want everything as simple as possible, and as streamlined as possible. But then there's Minecraft and Day Z, which are very complicated, and people like them a lot."

Receiver has been interpreted as a comment on violence in games, but while Rosen believes that's a positive message to send, Receiver was really fuelled by a belief that designers should challenge their preconceptions. With the medium still in its infancy, that instinct is vital to its continued progress, and to finding new audiences.

"Telltale's The Walking Dead proved that a more emotional experience is possible even with a creaking engine and mechanics several decades old"

"It's more about just being thoughtful in the approach to game design, instead of just taking things for granted and going with the standard tropes. It's important to think about why they're actually there. Receiver does seem like a hardcore game, but it reaches non-gaming audiences. We found that it really resonates with women who like guns. Most games that have guns are really integrated with a macho power fantasy: you're always staring at a pair of man-hands as they go around murdering everyone. But Receiver is about the gun itself. It's interesting what comes up when you go off track."

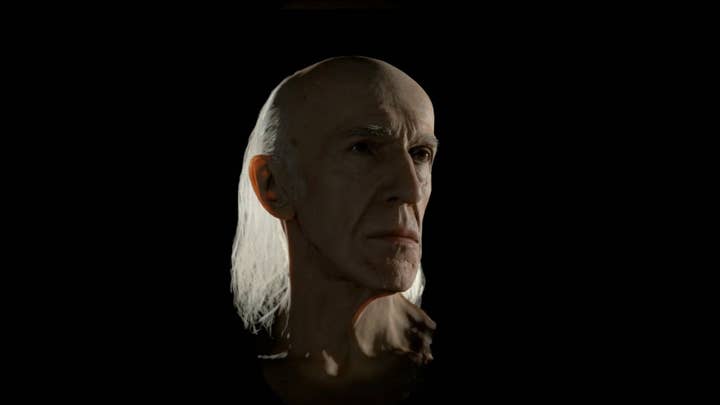

Within the mainstream, Quantic Dream's David Cage is perhaps the most vocal exponent of the industry's pressing need to go off track. For Cage, the end result - the golden ticket to new audiences and widespread cultural acceptance - is his oft-repeated mantra of "emotion." However, his unceasing pursuit of photo-realism makes the implicit point that the means to realise "emotion" in game design are beyond the grasp of all but the most well-funded of developers. In short, the salvation of mainstream development must necessarily come from within the mainstream, too.

Cage was also on-stage at the PlayStation 4 event, proselytising about the sparkling future of emotional games beneath the floating head of a dead-eyed old man. But if you played Quantic Dream's Heavy Rain and found it lacking the emotional punch it was so clearly intent on delivering, it likely had nothing to do with the lack of technical progress signified by Cage's decapitated geezer. Telltale's The Walking Dead proved that a more emotional experience is possible even with a creaking engine and mechanics several decades old. And Richard Hofmeier's Cart Life proves it can be done with pixel art and mini-games.

Games have the ability - unique in entertainment media - to place you directly into somebody's shoes and let you walk around for a mile or two. And yet, in the vast majority of cases, those shoes could never exist in the real world, or even a fanciful abstraction of the real world. If you play games - both AAA and indie - on a regular basis, there will seldom be any correlation between what is happening on-screen and anything that has happened in the history of mankind. Indeed, that is one of gaming's great strengths, but when pursued to the exclusion of all else it becomes a severe limitation. Unlike cinema, literature and music, narrative games harbour no interest in tackling life or anything remotely like it.

"You can adopt the lens of game making at any moment, in any setting. You can look at your own life as a video game. Real people have so much at stake. Everyone does"

Richard Hofmeier

Cart Life is different. Players are given a choice of three characters, all of whom must juggle the economics of running a food-cart with the struggles, large and small, of living in a drab, uncaring metropolis. You could be Andrus, a hard-working Ukrainian newspaper vendor with a pet cat and an expensive smoking habit. You could be Vinny, who needs endless cups of coffee to sell enough bagels to avoid being kicked out of his apartment. I chose Melanie, a single-mother selling espresso shots to raise $1000 for an imminent custody hearing.

The aesthetic is grayscale pixel art, the various tasks are represented by rote mini-games. You are never allowed to forget that you are playing a video game, and the juxtaposition of these familiar elements with unfamiliar subject matter fosters a curiously powerful sense of empathy. Cart Life is a game about details, and the way they both comprise and obfuscate the rest of life. It is also a game about the irrelevance of thinking big - the perfect tonic for a medium so obsessed with victory, scale and empowerment.

"You can adopt the lens of game making at any moment, in any setting," says Hofmeier. "You can look at your own life as a video game. Real people have so much at stake. Everyone does. There's an inherent drama there.

"In some sense it's my intention to change the world for the better - it's my dearest hope - but at the same time I feel irredeemably audacious to even say that. I'm kinda schizophrenic on it, frankly. And in the last few weeks I've been getting a lot of, oh man, life-changingly personal fan mail. I can't even begin to articulate what that kind of thing does to me. It's such a shock to communicate with somebody through this game that I never would have even met otherwise.

"When I first started [Cart Life] it was supposed to be a game about how bad games are, but a lot of that cynicism is gone. I hadn't equated myself with other folks making artistic or sincere games. I just didn't know. But as I became acquainted with the work of other people who had accomplished that kind of destructive thing with more convincing arguments or grace or beauty, I realised there's all manner of approaches to the same problem. We're all just trying to forget about Mario Bros. And Tetris."

And in Hofmeier's experience, the games press is almost as keen to put those dusty icons in storage. Cart Life is a strangely effective experience, but Hofmeier is the first to point out its many bugs, glitches and flaws. For the most part, though, these have been glazed over by critics and journalists who seem willing to forgive the sort of sins for which AAA releases are regularly castigated, in return for the invigorating gut-punch of Cart Life's social-realist agenda. It is the beneficial double-standard enjoyed by any developer willing, as David Rosen put it, to "go off track," but it's a double-standard that, for all its upsides, Hofmeier has trouble accepting.

"It's really hard to know whether we all have our heads up our butts collectively. What if we're just projecting our neuroses onto the retinas of millions of strangers?"

Richard Hofmeier

"It's really hard as a participant in this circus to know whether we all have our heads up our butts collectively, and maybe we think this is more special than it is," he says. "What if we're just projecting our neuroses onto the retinas of millions of strangers? I don't want to fall in love with independent games, or even games as a whole. I kind of think the [critical] language is restrictive and problematic, and we should just tear it all down and burn the remains."

But that cuts both ways, and Cart Life's adoption of gaming tropes to reinforce its underlying message placed it on the blade's more forgiving edge. As a former critic, I can vouch for the fact that, after months of reviewing racers and shooters, it's easy to lose site of where games of real daring fall short. An experience like Cart Life is restorative; it justifies all the hours spent labouring through homogeneous products, and any praise meted out is buoyed by the sense that you're drawing attention to something that would otherwise be ignored.

But how much innovation is even the press willing to tolerate? It's a question that Ed Key may well have pondered as the conversation around his latest game, Proteus, rapidly mutated into a debate over whether it was a game at all. This sort of semantic argument may hold some relevance for academics, but, as Key found out, even critics are willing to break out the Plato and the Wittgenstein when they sense too broad a challenge to their favoured pastime. All those years of defending video games have left a subtle, tribal echo.

"Game is such a nice, short, compact word - like film - that inevitably, if you want to be more specific about anything, you end up with a series of unwieldy, multi-syllabic, hyphenated terms," he says. "But those are always much longer and much emptier than the things they signify. In everyday experience, if you're talking about a bug that you can't fix, you don't say, 'I can't get my interactive art experience to run'. The de facto reality is that's what it's called - it's a game."

Like Dear Esther, Proteus seems to delight in giving the player nothing in particular to do. It demands patience and observation above all else; qualities not generally associated with video games. The idea sprang from a series of prototypes Key created around the process of exploration, and if it wasn't for the intervention of David Kanaga, an experimental composer, Proteus might well have ended up an open-world RPG. However, with Kanaga's input, the notion of a symbiotic experience where the player probed both the terrain and the music began to take shape.

The series of articles that followed its release led me to believe that Proteus would be passive and inert, but the reality is quite different. The world Key and Kanaga have fashioned is rich and textured, a dynamic and reactive landscape that responds to the player's presence in subtle and unexpected ways. Granted, the experience is difficult to express in words, and that may be what prompted certain critics to take an oppositional stance. Yet that very ability to elude literal description is precisely what makes Proteus so compelling. The meaning of the experience is defined through interaction alone, with no extrinsic motivators to offer objective guidance.

"I don't want to be prissy about this, but we should be encouraging that stuff, really," says Key. "That's got value. That's such a great skill to have: to be dropped in an environment and to figure out what to make of it and how to interact with it.

"If your game is a bit weak in what you actually do in it, an easy way to patch that is to just put in an XP system. That's grown a lot recently. It's very easy to market that"

Ed Key

"If your game is a bit weak in what you actually do in it, an easy way to patch that is to just put in an XP system. You have this simple way of validating what people are doing, and providing incentive to play a bit more. That's grown a lot recently. It's very easy to market that. It's a quantifiable thing.

"AAA games are full of tutorials and achievements and validation, and I deliberately stayed away from that, almost to see how far you could push it. The most satisfying feedback to get is when someone tried it once and didn't like it, but something compelled them to go back and they played it all the way through. It's fun to be provocative with people's expectations."

For Key, when people accuse Proteus of not being a game, their notion of 'game' seems to be informed by the marketing spend of the mainstream industry. Mobile and social may get more players, but AAA marketing dollars buy cultural prominence that has a strong influence over what the audience and, in some cases, the press will tolerate. And here's the truth: if Proteus stands in stark contrast to Killzone 4 and inFamous 3, then that might be just what gaming needs. For all the impenetrable polemics it inspired, it's difficult to imagine a more accessible and welcoming experience: fade up, and off you go.

"The phrase I hear a lot is, 'It's not for everyone.'" says Key. "But in a way we are trying to appeal to everyone. We're trying to make something that our elderly aunts can play. It's only 'not for everyone' if by 'everyone' you mean long-time gamers. It's good to have people playing it who don't see themselves in that way, or they've played games in the past and gone off them, but then they found Proteus."

For Hofmeier, Proteus is a prime example of the "destructive" approach to game design - an experience so far removed from stacking blocks, rescuing princesses and chaining head-shots that it can only benefit the medium as a whole. With so many games across so many platforms, it's easy to think that we already have a product for every possible taste, but that would be naive. Gaming needs to grow up, to diversify, to improve, and we all have our part to play.

"A game like Proteus needs to exist," says Hofmeier. "We're better for having it. If it can't be dissected with language, well, I like Proteus because it's sort of slippery and alive. As soon as it gets relegated to a genre or boxed in and simplified for means of classification, it kind of has to die for that to happen. How do you share Proteus with friends and family if you're really fond of it? You do it by saying as little as possible."

Fade up, and off you go.