Fig CEO: "The Kickstarter model sets game developers up to fail"

The investment platform reveals Portfolio Share as it attempts to halt the slide in video game crowd-funding

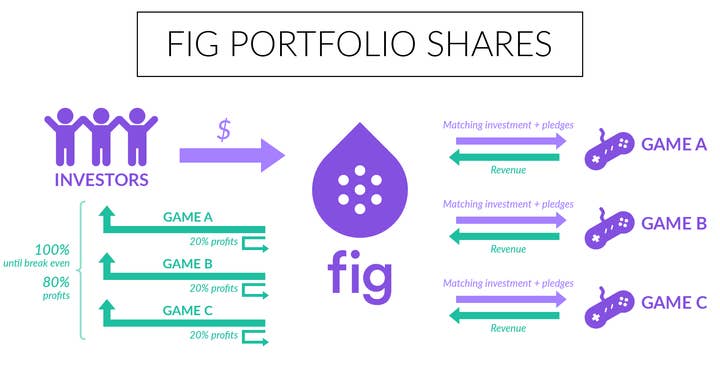

Crowdfunding specialists Fig is now allowing investors to back a portfolio of games funded through its platform.

The firm's Portfolio Share concept is currently only available to accredited investors, although may be opened up to general backers in the future. The concept is to allow investors to participate financially in multiple games, which will mitigate the risk of investing in just a single title.

Fig says more than half of the games funded through its platform so far have been profitable, with investors seeing returns from the likes of Outer Wilds (220% per share), Kingdoms & Castles (300%), Solstice Chronicles: MIA (143%), Psychonuts 2 (139%), Wasteland 3 (132%) and Phoenix Point (191%).

Fig launched in 2015 and was initially similar to Kickstarter in that games were put up for a limited time and had to raise a set amount of money in that period. The main difference with Fig is that investors could also acquire actual shares in the game to earn a return on their investment.

This year, Fig has been changing its offering. Alongside the new Portfolio Share, the company also introduced a new model called Open Access in May. Open Access removes the traditional time-limited (typically 30-day) campaigns as made popular by Kickstarter, and creates an open-ended, ongoing funding tied to a development roadmap. Backers can pay for certain reward tiers and by doing so will be able to play the latest build of an in-progress title. Funds go directly to the developers at the time of payment as opposed to at the end of a campagn.

Speaking to GamesIndustry.biz, Fig CEO Justin Bailey says the new changes are to put an end to the decline in crowdfunding and creating a new model more fit for how the video games industry operates.

"Crowdfunding games has been heading in a downwards direction. It has been for a long time," he tells us. "Our original premise was just like Kickstarter, and then we bolted on investment. We thought that would fix crowd-funding when we launched in 2015. Since then, we've had a lot of data and a lot of successful games. The majority of our games actually have generated profit.

"The actual Kickstarter campaign format is somewhat to blame for the decline in crowdfunding"

"We have never tried to go out and grab the whole market. One reason for that is because it's not just about [the game] getting successfully funded. It needs to be successfully developed and it needs to be commercially viable. There are a lot of games that we passed on, which were very interesting, very intriguing and very artistic, but we didn't view them as having a commercially viable place in the market. For this being successful, they need to be situated around earning money. Those three criteria do limit us in terms of the games that we take on."

The company has seen some big success with titles from InXile (Wasteland 3), Obsidian (Pillars of Eternity II) and Double Fine (Psychonauts 2), which are now all part of Microsoft Game Studios. But it's not all been established teams. Kingdoms and Castles has now generated $7 million in revenue off of a $100,000 campaign. Meanwhile, Outer Wilds, Phoenix Point and What The Golf have all generated significant interest.

"That's where we are. But still, when I look back at stuff, I'd like to see this [crowdfunding] segment growing. We were looking at all this information that came in, and we saw that the actual Kickstarter campaign format is somewhat to blame for the decline. We also looked at it and thought that individual investments in games, although interesting, is not the silver bullet that we thought it would be. We were getting feedback from the people investing, and the number one request was to be able to invest in all the games we did. As you can tell, in terms of hit rate, you'd usually see -- for publishers -- that one in ten games are successful. So for us, to have over half our games generating profit for our investors is somewhat unheard of."

Fig's Open Access concept was revealed in May and it's actually inspired by what a number of Fig developers have already been doing. Many of Fig's developers kept crowdfunding even after the initial campaign was a success. One example is Snapshot Games, who opened its own store and started selling its game [XCOM-alike Phoenix Point] through there. The result was the company generated millions of extra dollars in revenue.

"If you define crowdfunding as that Kickstarter format, then Shenmue 3 would be one of the most successful ones," Bailey says. "But before Shenmue came along, you had things like Prison Architect. Prison Architect actually generated more money through crowdfunding that Shenmue 3 if you're looking at how they did it. They basically put it up on their websites and started selling early builds of the game.

"And the biggest one of all, which is out-performing even board games, is Star Citizen. You can add all the board games on Kickstarter together, and Star Citizen is out-performing them. And they have the same format."

"Prison Architect actually generated more money through crowdfunding that Shenmue 3 "

Open Access is also designed to reduce the pressure on developers who may find their game has to change part-way through development, and thus risking anger from the community.

"If you look at why board games are really successful on Kickstarter, you can see why that format is not the best for video games," Bailey says. "For the board game, you're seeing a prototype of the finished product. That means the creator is just raising money to manufacture that product and fulfil it. So they know exactly how much money they need to raise. Once they've raised that, they know exactly the delivery date with very little variance. If you look at that whole process, the consumer knows what they're getting, when they're going to get it, and to what quality. Now enter video games... you develop a video game and you're getting feedback from the community, and that is going to change the scope of things. And the scope of things changing will push the time out further. You also have concept art, which is not indicative of what the final product will be. So the quality changes, the timing changes and the price changes.

"That's why we've adopted this Open Access, where you're funding alphas and looking at two or three milestones in the future. This is an evolving journey and you don't know where it's going to lead. What we've found is that by being transparent about that, and not trying to work around this rigid Kickstarter campaign structure, we're earning people's trust, gamers' trust and setting expectations appropriately. As opposed to taking this format that everyone has used before which, frankly, sets developers up to fail. The format makes promises that developers just aren't able to keep."

It's been an interesting year for Fig and crowdfunding in general. Business decisions around subscription models and the Epic Store have come under the spotlight (something Bailey hopes Open Access can help mitigate), while a number of its biggest development partners have since been acquired by Microsoft -- namely Double Fine, InXile and Obsidian.

"I think it's exciting for [those studios]," Bailey says. "We did have five or six interesting campaigns that we had in mind with Obisidian and InXile, which were at the early stages. But those projects now have full funding within Microsoft."

Yet despite the challenges, it's been a successful 12 months. Bailey says that Fig is profitable this year, and has generated between $4 and $5 million in revenue (versus $400,000 in 2017). It's just with studios and investors growing wary of crowdfunding, there has been a need for a different way of thinking.

"We do believe in this idea of getting the community involved early in publishing... we're a community publisher," Bailey concludes. "The community is effectively green-lighting these games. To all intents and purposes, they're reviewing the milestones and giving the feedback. And then they're offering their voice to promote these products. In an age where discovery is such a huge problem for game devs, we think this is one of the ways to solve that."