The Future of Games: We Need To Protect Our Past

With two of his games gone from the App Store forever, Will Luton asks if there's a better solution to preserving old games than piracy

"The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see" - Winston Churchill

In the last year I've seen two of my games silently slip from the App Store never to be playable again. This set me thinking on a problem that is unseen over the hubbub of next-gen chasing: we are losing access to our past.

Our games run the risk of becoming inaccessible as the data evaporates and servers retired. This danger is made more likely by self-interest of individuals and corporations, yet is fought against by those we criminalise. Here is why we need our history and how we can protect it.

"Our games run the risk of becoming inaccessible as servers retire. This danger is made more likely by self-interest of individuals, yet is fought against by those we criminalise"

In 1888 a group of well-to-do Victorians shuffle exaggeratedly around a garden in Leeds, West Yorkshire. This scene is remarkable in that, 125 years later, it's the oldest captured on film. Today it is readily available on YouTube within seconds.

Film, seen as culturally important, receives a comparatively liberal level of support of its antiquities. The British Film Institute, a charity afforded a Royal Charter, promotes the cultural and creative importance of film by protecting, restoring and distributing its relics.

What this meticulous preservation of film affords the world is an insight into the solution the medium discovered: The first reverse angle shot, the evolution of the montage et al. This informs academia, giving rise to formalised theory that pushes film forward.

Additionally, the collection also exists as a documentation of a society's constant metamorphosis, silently detailing, for example, how stresses of war gave rise to comedy escapism and sci-fi invasion allegories. Films, it is seen, documents a time intentionally or not.

Meanwhile, videogaming history remains largely ignored. Phoning the National Media Museum, who digitally remastered the 1888 Roundhay Garden Scene footage, resulted in voicemail boxes of since-departed staff and nobody knowing who, if anybody, ran their own National Videogame Archive.

"Firing up MAME is much more realistic than sourcing, transporting and installing a four player The Simpson Arcade Game"

As an industry we regularly spout videogaming's financial dominance over Hollywood yet we seem to shy from the discussion of our comparative cultural relevance, ostensibly afraid of our own perceived vacuity.

Yet video games have incredible cultural relevancy. Our industry has already seen movie tie-ins (both ways), Andrew Lloyd Webber pop songs, national moral panic, international crazes and IPs as recognisable as Disney's finest. But this is just the start. Mobile devices and the social web have expanded our reach well beyond the traditional boy's club, whilst the indie revolution allows thousands of creators to make experimental and non-commercial titles that challenge conventional wisdom and stagnant genres.

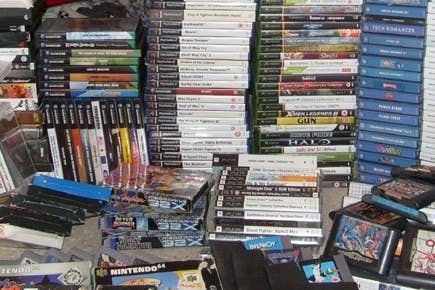

Videogames are significant in the lives of more and more people every year whilst academics struggle to formalise models to build understanding. Yet, despite private collecting increasing, the public cataloguing of our games falls to those we criminalise: pirates and hackers.

P2P file sharing has allowed for game data to be preserved, from dumps of original carts, discs or files on a scale happening nowhere else. The most obscure or forgotten game is today passing in binary from machine to machine via bittorrent, ensuring it's perseverance for generations to come. Meanwhile hackers are removing DRM, circumventing security and reverse engineer hardware to create emulators that allow the data to be usable.

However, this data is messy and the user experience sucks. Aligning the moons of ROM, emulator, config files and operating system is the kind of command line witchcraft that can make controllers meet walls at the pace of rage.

But still emulation is considerably more practical as a reference than the real thing. Firing up MAME is much more realistic than sourcing, transporting and installing a four player The Simpson Arcade Game for the sake of "seeing how they do the bonus stage".

"A single device that can give me complete unfettered access to the complete history of video games delivered digitally on a pay-per-title or Spotify-like subscription"

All of this frustration and law breaking has made me fantasise for a better solution: A single device that can give me complete unfettered access to the complete history of video games delivered digitally on a pay-per-title or Spotify-like subscription where I get great experience and license holders get paid.

The practicalities of licensing is likely to make this an impossibility for all but the most dedicated of startups, leaving devices like Ouya to occupy a middle ground of distributing emulators but no content. A no-win situation for all.

However, whilst many physical media games are emulatable or otherwise playable to a high degree of accuracy, non-standard controls systems aside, the new generation of always connected, always updating gaming is not such an easy proposition.

With EA's closure of The Sims Social and Pet Society, both important titles in the evolution of F2P and social gaming, is their legacy lost? Or indeed will we be able to study FarmVille's transformation by rolling between versions? Or are these games simply transient leaving only a recorded, non-playable history? Will hackers afford them the same level of reverse engineering that they have World of Warcraft which surely survive any official server closures?

I am unsure of the answers to any of these questions, however I am sure that these games, like all games, are worth protecting and preserving. Yet that protection requires the cooperation of a great number of parties.

I hope that as more and more social games get shuttered that the companies behind them provide the knowledge and access to technology, such as server code, needed to keep them in some form playable for ourselves and the next generations of game makers.

Furthermore, a British Film Institute equivalent is needed to not only protect the physical and digital history of video games, but also promote it. At the very least a company commercially exploiting these games by offering a library that is consistent, accurate and accessible for immediate play, offering a viable and legal alternative to piracy.

We need all these things to happen because if we lose contact with our past, making the future becomes much more difficult.