The Evolutionary Edge of Going Indie

Ex-Monolith devs at Blackpowder Games are like insects next to AAA studios, but in a good way

It's not uncommon for people to consider indie start-ups as insects next to their gargantuan AAA developer counterparts, but it's rarely a comparison that goes in the indie start-up's favor. Speaking with GamesIndustry International about the newly announced Blackpowder Games, former Monolith creative director Craig Hubbard (above, left) gave one insectoid quality in particular as an advantage he and a handful of his coworkers from the Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment studio are getting by striking out on their own.

"To use a weird metaphor, it's like how insects live for so short a time that they evolve very rapidly and adjust to environmental threats a lot faster than an organism that lives a lot longer," Hubbard said. "So with a small studio, to compare us to insects inadvertently, you can put out a game, see what's working and what's not, then put out another game, growing and learning much faster. That allows for games to get better and better very quickly, whereas at a big company, projects now are taking upwards of three years."

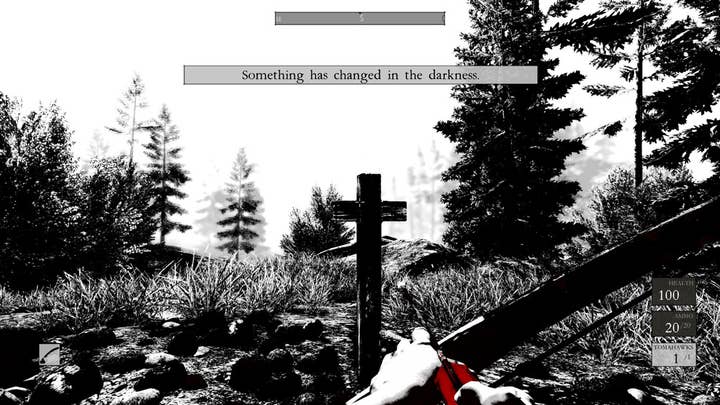

That speed can be seen in Blackpowder's first game, Betrayer. The studio was quietly formed in September, and by the end of this month, its six full-time employees will have the game far enough along to launch on Steam's Early Access alpha-funding platform. Larry Paolicelli (above, right), who handles the business end of Blackpowder and doubles as the user interface designer, suggested the game was ready to go almost before the company was.

"When we started out in September of last year, we were just excited to go make something," Paolicelli said. "We picked up the Unreal Engine and just started working. And in a way, we got so focused on the product and the game that we skipped things like getting funding, or doing Kickstarter, or even announcing ourselves. We just got completely product focused and started cranking on the game. When we realized that we had something viable that was going to be good, we had to poke our heads up and say maybe we should set up our company."

That desire to focus on the product, to make games instead of conduct meetings, was a key part of why the group left Monolith in the first place.

"You think about a big publisher, it's not just a team," Paolicelli said. "There's an operations group, a huge marketing group, a PR group. There are the executives that have to figure out which bets to place their money on. So if you have a team of 50 or 100 people, behind that is another 50, or 100, or 2,000 people. So it starts to become exponentially more difficult to keep not just the team focused, but the whole company focused on what are the best creative choices you need to make. And if you go to a smaller group of people, the focus and communication becomes very easy and clear, and you can move a lot faster."

Hubbard said one of the big problems with the AAA model of development is that changing things mid-stream is such a difficult process that it pushes the developers to make all the important decisions about their games up front.

"If there was a formula, Hollywood would never lose money on a big tentpole movie, which they're still obviously capable of doing."

Craig Hubbard

"The thing with software development is you really can't foresee what it's going to be until you've gotten a certain distance into it," Hubbard said. "We just wanted to be back in that situation where we could really react to the product we were making as opposed to the product we thought we were making without having already tied ourselves to ideas on paper that may not pan out...When you've got that much investment, it's so much harder to change things that need to change. So if you don't change them, you're going to end up with a mediocre product that people aren't going to buy. But if you do change them, instead of 20 people that have to adjust to the change, now you're steering a whole organization."

That puts AAA developers in a bit of a Catch-22, and only heightens the difficulty of trying to do something innovative on a game with a huge budget.

"When you're investing millions of dollars in a project, you really want to make a safe bet because you need to sell a certain number of units to make any kind of profit," Hubbard said. "It tends to generate a sense of anxiety about every decision you make, which pushes people to want to try and turn guesswork into more of a science. But it's still ultimately just guesswork. If there was a formula, Hollywood would never lose money on a big tentpole movie, which they're still obviously capable of doing."

With just six full-time employees and some contractor assistance, Blackpowder has the luxury of making design decisions from the gut instead of a focus group. (From the start of development, Hubbard said the game's tone, focus, and visual style have all shifted significantly.) But the studio doesn't plan to stay quite this small forever.

"We really see it as a foundation to grow from," Paolicelli said. "The important thing was to get our feet underneath us and be fully independent. We haven't taken any VC money. We haven't even done a Kickstarter. And we don't have any publisher support because we didn't really want any at this time. Ultimately what we'd like to be is a 20- to 30-person studio, and keep the communication and focus on the products. When you get to big 50+ person teams, you start to lose that. We definitely want to grow, but we see what we're doing right now as foundation building."

One trend working in Blackpowder's favor has been the rising visibility and viability of independent development. From funding to distribution, the barriers to entry for indies have been lowering across the board.

"Consumers are looking for different things a little bit," Paolicelli said. "I think a lot of that has to do with how hungry they've gotten for something a little different. And it's very refreshing to see that, because we wouldn't have this market, this indie thing, if it weren't for gamers out there embracing what indie developers are doing."

Hubbard agreed, saying expanding audience tastes is a self-perpetuating trend. Each indie hit that tries something different expands the audience's comfort zone a little, and making it possible for the next indie hit to push that comfort zone even further, and so on.

However, not everything about the move to indie development has been going Blackpowder's way. AAA development may be notorious for long periods of crunch, but Paolicelli said the biggest surprise of indie life for him was just how detrimental it was to having a social life. Even so, the crunch tends to be more bearable when it's self-imposed.

"Now you're doing it for yourself, so your motivations are different," Paolicelli said. "While it's isolating and a little bit tighter, it's so much more creatively refreshing to work that way."