The case for a smaller, more portable Nintendo Switch | Opinion

Portables were said to be dead -- so why would Nintendo consider releasing a smaller Switch?

Earlier in the week, the Wall Street Journal reported that Nintendo plans to release two new variants of its Nintendo Switch console later this year. One variant is suggested to be some sort of updated take on the current Nintendo Switch with, "enhanced features targeted at avid gamers." The other, according to the report, will be a smaller, more portable, more affordable version of the Switch that is designed to replace the Nintendo 3DS as an entry-level games device.

Both devices, the report suggested, could be unveiled as early as this Summer.

Now, releasing a new Nintendo Switch model with incremental improvements over the current Switch makes perfect sense. In today's extremely competitive environment it's simply the done thing, and all console makers do it with varying degrees of frequency. Nintendo itself has released enhanced variants of its Nintendo DS and Nintendo 3DS systems in the past, so no surprises there.

On the other hand, a smaller Switch variant that's designed to replace the Nintendo 3DS isn't quite as easy to understand. The Switch is already a portable games device that does what it's meant to do wonderfully. Why does it need to be even smaller? What purpose would that serve?

"The Switch is already a portable games device that does what it's meant to do wonderfully. Why does it need to be even smaller?"

It's a fair question. After all, just a few years ago, the games industry as a whole seemed to be calling for an end to smaller, more portable gaming devices in favour of smartphones.

It began in 2011, a few months after the Nintendo 3DS had been released. In July of that year, Nintendo reported disappointing Nintendo 3DS sales, and announced that it would drop the price of the device from $250 to $170. There were a number of reasons for the disappointing performance of the 3DS, chief among which was that it was simply too expensive for its target audience. This was further compounded by the fact that it suffered from a weak portfolio of games at launch, leading to soft initial demand. While the 3DS would eventually go on to be a success, with 75 million units shipped -- that's more than the Xbox One, to put things in perspective -- it never quite recovered from the damage done early in its life.

Despite the number of complex factors involved in that slow start, by late 2011 industry gurus and analysts had boiled it down to one very simple hypothesis: smartphones were the future, and nobody wanted to carry a second portable device around with them.

After all, if you were "on-the-go," how much gaming were you really expecting to do? And if it was simple time-killers you wanted to play on the train, smartphones could provide you with a great many of those for free. Whether or not you agreed with that assessment didn't matter. Most of the industry had already decided this was an accurate read on the situation, and Western publishers swiftly dropped support for the Nintendo 3DS, looking instead to the microtransaction-driven business model on smartphones, which was opening up new avenues of revenue.

Meanwhile, the "hardcore" gaming contingent was also mostly in agreement that portables no longer had a place in the world of games. "Real" games, they reasoned, belonged exclusively on a big screen, with big budgets and big graphics and big explosions. Nobody cared about a game device in the palm of your hand any more, when you could have eye-popping 1080p instead. Everything needed to be bigger and better and more awesome, or there was simply no point.

"A more portable Switch actually does make a lot of sense -- just not for the audience that likes to debate these topics on the internet"

Again, the industry complied. Games got bigger and even more expensive. Open worlds became the norm. The hardware required to support these technological leaps got beefier as well. The support the Nintendo DS and PSP had enjoyed from Western publishers in years past dried up, leaving the Nintendo 3DS to fend for itself, supported primarily by Japanese developers and the occasional indie studio.

So why bother? All these years later, why release a smaller, more portable Nintendo Switch when there simply doesn't seem to any evidence that such a device is even required? The current model serves its purpose just fine. You can carry the thing to bed, or pop it into a bag while travelling. You can take it to a friend's to play a few games of Mario Kart or Smash. When you're done, you can hook it back up to your telly at home for some Fortnite or Doom. It works, and it works well. The Switch has already found an excellent balance between the flexibility of a portable and the oomph of a home console. A smaller model -- one that you may not even be able to connect to the TV -- makes no sense, surely.

Therein lies the rub. A more portable Switch actually does make a lot of sense, just not for the audience that likes to debate these topics on the internet.

Here's the thing: there are certain games and certain audiences for whom a smaller, more portable device is simply a better lifestyle fit, and always has been. These are audiences the industry has a tendency to overlook even today, but they've historically made up a significant part of Nintendo's userbase, and will continue to do so in the months and years ahead.

Here's an example: the chart above was presented by Nintendo to investors in 2013. It shows you the age and gender bias of consumers in Japan that bought Animal Crossing: New Leaf along with a Nintendo 3DS.

At the time the game was released, the 3DS userbase in Japan was 69% male and 31% female. And yet, when Animal Crossing made its way to the 3DS, 56% of the game's players were female and just 44% male. It actively encouraged more women -- especially those in their 20s and 30s -- to purchase a Nintendo 3DS and use it. Six years later, Animal Crossing: New Leaf has sold over 12 million units, and has considerably diversified the 3DS userbase in the process.

"Animal Crossing: New Leaf actively encouraged more women to purchase a Nintendo 3DS and use it"

Animal Crossing isn't necessarily one-of-a-kind either. There are other Nintendo 3DS games that have helped diversify the 3DS audience, too. The Style Savvy series, where the player runs a fashion boutique and puts together outfits for their customers, is almost squarely aimed at women, and like Animal Crossing has helped the device pull in a greater number of female users. It's been successful enough that Nintendo has released four separate Style Savvy games on the 3DS alone, with the first having shipped over one million units worldwide by itself.

A lot of the people that play games like Animal Crossing and Style Savvy don't really care to settle into a couch in front of their 50-inch TV to get their game on. They're precisely the sort that primarily plays games on their smartphones, but are also happy to dabble in the occasional "casual-core" game when the right one comes along. And a smaller, cheaper device that's lighter and less unwieldy makes more sense for them than the current Switch, which is too pricey and perhaps unnecessarily sophisticated.

Next up, you have Pokémon.

Every major new Pokémon game has sold 16 million units on average since 2002, and while the series has made strides into the realm of online play, it's still very much a social experience that's made better when you share it in person with other players. A lot of the people that buy and play Pokémon games are school kids or college students. They carry their Nintendo 3DS with them to school, either to play on the bus or with their peers in between classes, which is something you can't really do with a device as large or as expensive as the Nintendo Switch. Again, a smaller, more durable, more portable device would facilitate this sort of experience a lot better.

Portability aside, a lot of kids that are into Pokémon are also in the habit of playing with their siblings, but in order for that to work you would need to enable the ownership of multiple Switch consoles per household, and that simply isn't going to happen at a $300 price point. Once again, for this audience, a more affordable variant of the Switch makes far more sense than the current model.

Finally, there's Japan, Nintendo's home market.

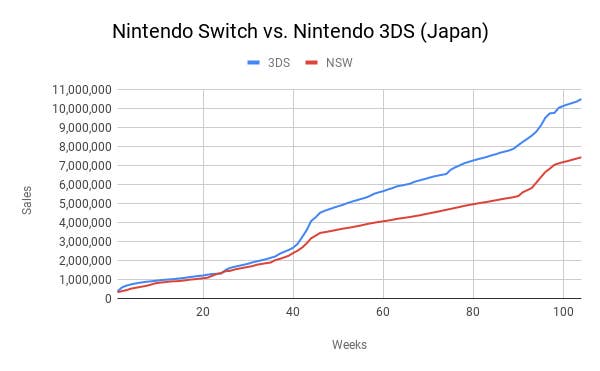

Portable game devices have long been king in Japan, with consoles taking a backseat to the convenience of being able to play games on the bus or the train or without the need for a television. A full one-third of Nintendo 3DS hardware sales (about 25 million units) are from Japan, and no other platform since has come close to matching its sales trajectory. Even the Switch, which is currently the best-selling gaming device in Japan, isn't doing anywhere near the numbers that 3DS was in its first two years (see the graph above, sourced from Media Create), and the only way to address the issue is -- you guessed it -- to release a more portable, more affordable model that better suits the lifestyle of the average Japanese consumer.

With a new Animal Crossing and Pokémon Sword/Shield coming in 2019, it makes a lot of sense for Nintendo to announce a portable Nintendo Switch this year. There's even been talk from Capcom about a new Monster Hunter for the Switch, and with Monster Hunter: World squarely aimed at the West, one would imagine a Switch game would be more inclusive of the Japanese market, where the games typically sell around four million units apiece. In Japan, Monster Hunter is largely treated as a local co-op game where each player has access to their own screen, making a portable Switch the perfect platform.

With all these major pieces of software starting to fall into place, the time for a more appropriate accompanying Switch model feels right.

"A full one-third of Nintendo 3DS hardware sales are from Japan, and no other platform since has come close to matching its sales trajectory"

And really, reports of a smaller variant of the Switch aren't surprising in the slightest -- not just because it makes sense, but also because variants are something Nintendo has been planning since before the Nintendo Switch was even announced. It was in 2013 that the company first merged its home console and portable hardware development groups, with the idea that all future Nintendo devices would share operating systems, built-in software, and even software toolkits -- just like smartphones and tablets. This would allow Nintendo to create multiple hardware devices running off the same OS with relative ease.

In fact, the goal wasn't just for all devices within a single hardware generation to be running off the same OS and architecture, but all future Nintendo devices, so porting games between them could be made easier, too. This, Nintendo felt, would also help alleviate software droughts when launching new devices.

"Currently it requires a huge amount of effort to port Wii software to Nintendo 3DS because not only their resolutions but also the methods of software development are entirely different," former president Satoru Iwata said at the time. "The same thing happens when we try to port Nintendo 3DS software to Wii U. If the transition of software from platform to platform can be made simpler, this will help solve the problem of game shortages in the launch periods of new platforms."

Iwata later elaborated: "To cite a specific case, Apple is able to release smart devices with various form factors one after another because there is one way of programming adopted by all platforms. Apple has a common platform called iOS. Another example is Android. Though there are various models, Android does not face software shortages because there is one common way of programming on the Android platform that works with various models. Nintendo platforms should be like those two examples."

If Nintendo were to pursue this line of thinking, it would make a hypothetical "Switch Mini" a relatively easy product to put out, and even a "Switch Pro" as suggested by reports.

Couple that with some of the comments Nintendo have made recently about growing Switch sales, and there's a rather compelling case to be made for different Switch models serving different purposes. Case in point: speaking with investors in January, current Nintendo president Shuntaro Furukawa stated that one of the next steps in expanding the Switch's userbase is to create demand for multiple Nintendo Switch consoles being owned within a household.

"In a survey of households asking how many family members use Nintendo Switch, we found that, while a certain number of households have multiple family members who play on a single console, some households have already purchased multiple consoles," Furukawa said. "Going forward, we aim to generate such demand among consumers as they feel like 'I want to have my own Nintendo Switch console' through measures such as software offerings, not necessarily so that each person will have one, but so that each household will have multiple Nintendo Switch consoles."

While Furukawa cites "software offerings" as the key to accomplishing this, that is very likely not the full story. A single household owning and using multiple versions of the same home console is a relatively rare occurrence, no matter what kind of software you release for it. But multiple portable devices? That's been a thing since the original Game Boy, and a "Switch Mini" type of device would be no different.