Telling story through gameplay

In a case study looking at Grindstone, Kaitlin Tremblay explains what it means to tell stories in games that look like they may not have a lot of space for narrative

Grindstone isn't what you would necessarily think of as a "narrative game." But since I've been working with the team on Grindstone's updates in the past year and a half, there's one question I'm consistently asked: "How do you create story for a mostly gameplay-focused experience?"

Grindstone is a brutal puzzle game, a twist on the match-three mechanic where you're playing as a barbarian slicing your way through like-colored monsters. The gameplay is crunchy and the puzzles are front and center. But this doesn't mean there isn't space for a lot of storytelling -- it just means that the storytelling looks a little bit different than what we might expect.

I wanted to write a narrative design breakdown of Grindstone, walking through the major narrative features to talk about how the team and I have implemented story into a mostly gameplay-focused experience.

This article will focus on these four approaches we've used in Grindstone:

Using gameplay verbs and setting to establish a story baseline

Part of what makes Grindstone's story and setting work is how well tuned it is to gameplay in the first place. The setting is established cleanly as a way to contextualize gameplay: this is a world where being a barbarian is a 9-to-5, and it's set in a small, blue-collar town where monster guts and the grindstones that come out of said monster guts is the main economy. Everything in the setting revolves around grindstones, the same way the gameplay loops revolve around creating chains to generate grindstones.

These two facets, the setting and the gameplay, are immediately working hand in hand, even before anything like characterization, story arcs, and worldbuilding is added to the game. They're working in tandem, which means that even if this was the only narrative that existed in Grindstone, you'd still get a solid feel for what kinds of stories could exist in this game.

That's because the base verbs of the game are already stitching together this story: you're a treasure-hunting barbarian fighting monsters, and each of your successes and failures in any given level is creating a sort of plot around you. Did you fail at a boss, grind out a few lower levels to get better gear, and then go back and slay the heck out of that monster? That's a training montage (well, kind of, but you get my point).

All of that sounds epic! And it is. Except the Grindstone team wanted to give this implicit story a slight twist via explicit story and worldbuilding. So while all of the above is true (you are a treasure-hunting barbarian fighting monsters), it's not epic in the world of the game. In Grindstone, it's just your job. You play as Jorj, a hulking stonegrinder, who is a family man at heart, and who just wants to work his gruesome 9-to-5 in order to save up enough money to take his family on a vacation.

The team used the inherent fiction that already existed within the gameplay (being a barbarian fighting monsters and getting treasure) and juxtaposed that against explicit worldbuilding to provide story and character motivation (being a barbarian is akin to being a miner, and it's more back pain than glamour). And it works! Layering this blue collar, mining town vibe over top of an epic and brutal treasure hunt creates this really tangible story that is easy to connect with and provides a lot of in-roads for understandable characters.

None of the story sits outside of what you're experiencing, moment-to-moment as a player

And it's all rooted in gameplay. You're chopping up monsters and finding treasure, both in terms of story and gameplay. None of the story sits outside of what you're experiencing, moment-to-moment as a player.

With each chain of like-coloured Creeps you're creating, you're telling Jorj's story. You're helping him save up to take his family on that vacation. Every action you take as a player is creating Jorj's story, because Jorj's story is told through gameplay and supported by the setting expressed in the level design and art direction.

Tying lore with progression mechanics and employing synecdoche in world-building

When I joined to work on the bestiary, which would eventually become Hëlga's Slöp Höuse, I wanted to build on what was already working so well in the game: a combination of blood, gore, and family values.

The Slöp Höuse pages were a lot of fun to write, because it was a license to expand the world, while also surfacing all of the existing stories, lore, and thoughts the team already had about Grindstone. Gameplay, art, level design, programming -- all of these bits were already informing what the world was, who the characters were, and what narrative pillars were important to the game.

It made the task of writing up a bestiary for all the sentient creatures in the game really fun, because I could spend hours picking the brains of the team, finding out what they liked about each creature, what thoughts went into their initial creation, and build up the text entries from there.

I had two goals: I really wanted it to be funny (specifically, I wanted to make both players and the Grindstone team laugh), and I wanted it to feel large, like there was a whole world that existed far beyond the seams of the sentences and the names of the characters.

With worldbuilding, I'm a big proponent of creating intentional gaps for players to insert their own thoughts into, giving just a taste of an idea to spark their own imagination. I then like to juxtapose this with concrete synecdoche (my favourite literary term, meaning letting something tangible stand in and represent a larger whole). Things like referring to a Creep Olympics (see image above), or suggesting at a now-lost Creep Civilization, or a reference to a Jerk War, were all ways for me to begin to poke at what the larger world outside of the game could be, while tying these bits to (hopefully) funny jokes about the enemies.

I wanted it to feel like there was a whole world that existed far beyond the seams of the sentences and the names of the characters

Rather than explicitly stating and defining the entire world and how all of these creatures intersect, I wrote specific instances that could represent larger ideas or dynamics, letting this use of synecdoche help to create these sort of intentional gaps that are purposefully open for interpretation and player imagination.

But that wasn't where we stopped. Because Grindstone is so gameplay-driven and because when we started working on the bestiary Grindstone was already released, we didn't want the bestiary pages to just be collectibles. We wanted them to be tied to gameplay itself, in a way that was above and beyond the manner in which players collected the pages. So from its initial conception the plan was already to tie the entire bestiary together with a brand new gameplay progression loop that would grow and constantly be revisited by players.

This introduced the "snack item loop," where with each kill of a certain enemy type you are filling a slop bucket up with their guts! Each page of the bestiary contains a kill tracker, and each kill corresponds to a certain amount of "slop" (aka guts) that fills up Hëlga's slop bucket.

It surprised zero people that one of the first major Grindstone features I worked on combined cannibalism as a gameplay loop and lore

So when the slop bucket hits a certain threshold, you can craft these all-new items, or snacks, that are one-time use, but with a really powerful effect. The general story here is: if you're killing a lot of enemies, and we're tracking how many of each enemy you're killing, then it makes sense that Hëlga would be using all those guts to cook snacks for you to then eat! I think it surprised zero people that one of the first major Grindstone features I worked on combined cannibalism as a gameplay loop and lore.

In the end, the bestiary wasn't just a bestiary! It would've been funny and cute if it was, but tying the lore pages to a gameplay progression loop really gave it life and more seamlessly integrated it into the gameplay experience.

Using synecdoche meant I didn't have to write more than was necessary to sell the joke and the world, and having the page collection tied to a new item progression loop meant it gave a bit more depth to the world of Grindstone and the characters who inhabit it, without needing to massively interrupt the player's flow through the levels and puzzles.

Narrative symmetry and character dialogue affirming player actions

The Daily Grind is a daily challenge mode where players compete to get the highest score possible in pre-defined levels that shuffle and change every day. It's Grindstone's main competitive mode, and early on, there was an intentional decision to make sure that this daily mode was also backed by a strong setting and thematic. Thus, Jjertrude was born.

Jjertrude is the voice of the daily leaderboards, meant to coax and cajole, and occasionally offer encouragement and praise to players. She's also the voice of competition in Grindstone, and both her indifferent attitude toward other stonegrinders and her reverence for herself are meant to be a friendly type of trash talking.

With Jjertrude in the Daily Grind, we knew we wanted her to be a priest, but with a stonegrinder twist. The thinking with her was to gesture toward what religion and spirituality looks like for the humans of HjellHjole, without revealing too many specifics so as to bog down play.

Jjertrude's dialogue, and the rules of the Daily Grind itself, revolve around creating a motivation to leaderboard play: sacrifice grindstones to the Old Gods to show you're devout. This kind of narrative symmetry with gameplay is really important to Grindstone. The narrative should help explain the gameplay, and the gameplay should feel right at home in the narrative.

So for this, it was important to create Jjertrude as an NPC who would reflect the player actions and provide setting and context based on how the players themselves engaged with the leaderboard mode.

The narrative should help explain the gameplay, and the gameplay should feel right at home in the narrative

There's a small amount of contextual dialogue in the Daily Grind. Jjertrude has unique dialogue lines for the obvious cases: if a player succeeds at a run (posts a score to the leaderboard, no matter of their position), if a player fails (does not post a score because they died during a run), or if a player flees from a run. Jjertrude reacts in character to these situations. She's self-satisfied if you lose, condescending and patronizing if you flee, and begrudgingly accepting and approving if you succeed.

But there are other instances where we used conditional dialogue, such as if a player jumps between daily modes (Greed, Quick, Fortune) without picking one. The idea is to basically have Jjertrude reveal facets of her personality based on specific context triggers, to make her three dimensional and reactive. This does two things:

- It acknowledges the player's behaviour, showing the game is responding to them

- It lets Jjertrude's personality shine through

Because the Daily Grind thematically was designed in such a way where the narrative resonates with the gameplay (they are not at odds with each other, but instead designed in such a way that the core of each speaks to each other), we had solid grounding in order to implement conditional dialogue that involved players in the setting and put them in direct dialogue with Jjertrude.

Having our mode rooted in a strong narrative context meant that the work of establishing stakes and story is already embedded in what players are doing, so it gave me space to let dialogue reflect that player agency in a really natural way.

Story conclusions that aren't game endings

With both the Slöp Höuse and the Daily Grind, I really wanted to write NPCs who added to the already rich tapestry of existing Grindstone characters, while keeping the focus primarily on the player and gameplay. Each new major feature in the game has an NPC attached to it, whether it's gear, tutorials, or the leaderboard mode.

Everything is diegetically a part of HjellHjole and Grindstone Mountain (even the game's update text is written as a work memo from Jorj's boss, Bossmin), and that makes connecting story and gameplay a lot easier, because characters naturally bring stories with them.

Everything is diegetically a part of HjellHjole and Grindstone Mountain, and that makes connecting story and gameplay a lot easier

But that doesn't mean there isn't a central story to Grindstone. There actually is! As Jorj progresses up the mountain, each distinct area ends with a big boss battle. Sometimes these bosses are straight up creature features, like the Vine Hjeart boss Creepzïlla. But there's one recurring boss, a wild-haired stonegrinder turned evil, named Jjary. While Jorj is doing his job on the mountain, he's constantly being interrupted by Jjary, who taunts and goads Jorj, but is also sort of running away from him/the player.

Which brings us to Lost Lair. Lost Lair is an upcoming update to Grindstone and is a conclusion of sorts. It's not the end of the game by any means, but it is the end of Jjary's story, because it revolves around the concept that it's Jorj's final showdown with Jjary.

Up until this point, Jjary is really trying to kill Jorj. So when we started talking about adding a new area to the main map, over a year after launch, the idea of it being Jjary's hideout was an easy choice. Capy artist Ben Thomas already had done a concept for what was essentially the Scrooge McDuck version of Jjary's lair, which coincided perfectly with the idea lead programmer Ken Yeung and I were forming of having the new area be an old abandoned grindstone mine that Jjary has repurposed into his lair.

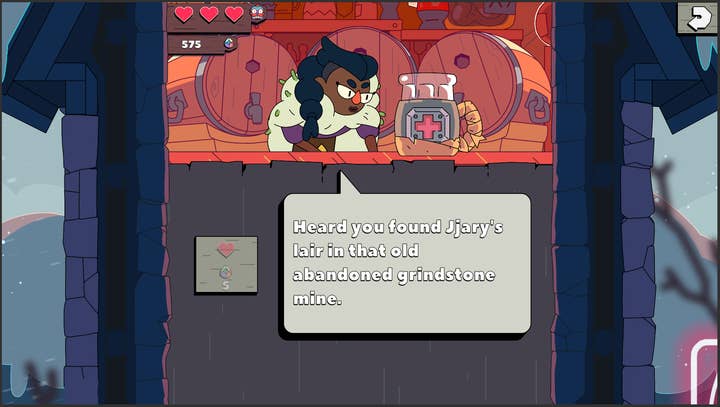

So as you're progressing through Lost Lair, there are little hints suggesting a final showdown with Jjary is coming. He taunts you even when you're not about to fight him. And even other NPCs in the game react to your presence in this area, a narrative device we so far hadn't used in Grindstone.

This is actually one of my favourite parts of Lost Lair. We added new dialogue from each NPC (Lagr the bartender, Knifr the blacksmit, Ødger the tailor, and Hëlga the cannibal) in the Howling Wolf Inn, which plays right before you're about to fight Jjary for the last time. Because during Lost Lair you're collecting pieces of a sword as you progress through the new area, you'll eventually have to return to Knifr to craft this sword. This was a natural opportunity to have the characters in the world mark the occasion.

It should feel monumental, and rather than injecting moments of dialogue and story that aren't tied to gameplay, why not use the crafting loop as the moment to have each character reflect on the fact that you're finally confronting Jjary, once and for all?

I've been really intentional about setting up a history, a reference to the lives and pasts of the characters that exist outside of Jorj

Additionally, something I've been really intentional about with Grindstone is setting up a history, a reference to the lives and pasts of the characters that exist outside of Jorj. So Lagr, Knifr, and Ødger all speak to this shared history with Jjary and suggest at the loss the community in HjellHjole felt when Jjary broke bad and holed himself up on Grindstone Mountain. So it's this nice, small moment, which players aren't forced into engaging with, but that just exists ambiently.

These characters will talk about your fight with Jjary as you're crafting your final weapon and getting geared up to take him on for one last final time. (Of course, there's a short cut-scene that triggers after you defeat Jjary in the Lost Lair, but I won't spoil that.)

And then, after all that, and after defeating Jjary for the final time, Jorj's life goes back to the grind. He wasn't on the Mountain to defeat Jjary, after all. He's a stonegrinder, he's on the Mountain because that's his job, which he has to keep doing. So life, and the game, goes on.

So, yeah Lost Lair is a conclusion, but one that's purposefully left open for Grindstone to continue to evolve and grow. This type of expansive narrative design is important, not just for live games, but for the type of worldbuilding that echoes in the game.

I don't have to pry open the game's ribcage to make room for new story beats; as the game grows, so does the story, because the game is the story

Grindstone is about a dad, a community, and a mountain full of monsters, and with each update comes a chance to continue to let this world breathe a little bit more. This expansion is directly linked to the way in which story is integrated into gameplay, rather than being polish on top of the puzzle experience. Without story and gameplay built together as part of the same skeleton, this type of expansive narrative design would be much harder. I don't have to pry open the game's ribcage to make room for new story beats; as the game grows, so does the story, because the game is the story.

Conclusion

Narrative design for games that don't typically look like a narrative game or a plot-driven game is a lot of fun! And it's no less challenging, in terms of storytelling. Developing characters, finding the threads for gameplay-driven story arcs, and letting the player's actions co-author the story alongside you as the writer requires the same command of narrative devices, structure, and craft -- it just gets employed with slightly different intentions, different areas of focus, and different proportions of narrative weight.

And just like with any type of narrative design or writing for games, it's an immensely collaborative effort, working with all facets of the game to make sure the characters, story arcs, and bits of lore that are added are seamlessly integrated into gameplay. It's essentially applying narrative technique to gameplay, since gameplay is also functioning like a narrative device in a game like Grindstone.

Kaitlin Tremblay is the lead narrative designer at Capy Games. Previously, she was a team lead narrative designer at Ubisoft Toronto on Watch Dogs Legion and was the lead writer on the narrative-driven, death positive game A Mortician's Tale from Laundry Bear Games. She can be found on twitter at @kait_zilla and her work can be found on her website.