Stock Ticker: DeNA vs Gree

Tracking the performance and prospects for Japan's mobile gaming giants

Unless you've kept a very close eye on global developments in the mobile gaming market, there's a good chance that 2011 was the year in which you first heard of either DeNA or Gree - a pair of Japanese mobile gaming giants who made their first major overseas headlines with high-profile western acquisitions in the past 12 months or so. Back in October of last year, DeNA acquired top mobile developer ngmoco in a deal valued at around $400 million; domestic rival GREE followed suit in April of this year with a $100 million acquisition of mobile social gaming network OpenFeint.

Since then, both companies have flitted in and out of the news in the west - with DeNA in particular attracting coverage thanks to building relationships with a host of high-profile developers, with just a quick glance at the firm's recent corporate announcements revealing tie-ups with Level 5, Namco Bandai, Grasshopper Manufacture and MapleStory operators Nexon (whose own recently mooted IPO has seen them described as the "Zynga of the East" in some quarters). Less favourable coverage has stemmed from a new lawsuit in Japan, in which Gree filed suit against DeNA, accusing it of anticompetitive practices.

But what do these two companies actually do? The answer isn't actually immediately apparent, and it's impossible to characterise either firm by creating a comparison with a western equivalent. They are very much a product of the unique Japanese mobile phone market, which until recently developed largely in isolation from the rest of the world's telecoms markets, and continues to have many characteristics that are quite different from what we're used to in Europe or the USA.

Gree and DeNA are coming from a very different social and technological background to the western companies with whom they are now merging, and competing

Let's talk first about DeNA. Initially founded as a mobile auction site back in 1999, the company didn't actually launch its gaming platform, Mobage (a contraction of "mobile game" and pronounced accordingly) until 2006. As a service, Mobage is effectively a hybrid of a gaming platform and a mobile social network. It's important to bear in mind that we're not originally talking about a smartphone platform here, nor are smartphones the key platform for Mobage at present. Japan's "featurephones", long envied for their advanced functionality by western gadget geeks before the rise of iPhone and Android effectively leapfrogged them, are Mobage's home platform, and indeed many Japanese featurephones are equipped to access the platform out of the box.

This is a point that's crucial to understanding not only DeNA but also Gree, and the challenges both companies face. They're coming from a very different social and technological background to the western companies with whom they are now merging, and competing. Facebook, for example, has been almost entirely irrelevant in Japan up to this point, while it's been at the heart of the rise of social gaming in the west. Social networking, like many other internet activities, has traditionally been seen as something you do on a mobile phone by Japanese consumers, where western consumers have tended to see it as something you do while sat at a computer. As such, platforms like Mobage have grown up in isolation from the likes of Facebook, a fact that has almost certainly helped them to thrive.

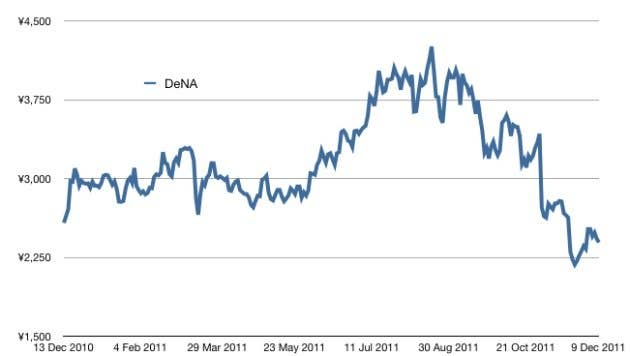

Yet a look at DeNA's numbers this year reveals that thriving isn't necessarily the right word. They're far from being awful - as we'll see shortly, the company is still just about outperforming the Nikkei index - but there have been a series of falls since August, when the company announced financial results which failed to meet expectations and, worse, suggested that growth may have flattened out somewhat, at least temporarily. Despite the ngmoco acquisition and its high-profile signings, there's evidence that DeNA may be struggling a little with the transition from featurephones to smartphones, and from being a local to a global player.

No such growing pains, apparently, for Gree. The company's background is rather different to DeNA's story - in fact, it commonly draws comparisons with Facebook's background, largely due to founder Yoshikazu Tanaka, one of the world's youngest self-made billionaires, who developed the initial Gree social network as a hobby and launched it in beta in 2004. Like DeNA, Gree is very much a product of the Japanese mobile market, with much of its growth being provided through deals with network operators for inclusion on their featurephones. It, too, faces the challenge of moving from featurephones - a safe and semi-closed environment - to smartphones, which have an entirely different business model and introduce aggressive new competitors from overseas.