Steve Gaynor: “Gone Home is the defining game of my career”

Five years on, the Fullbright founder reflects on the impact his team's seminal exploration game has had on the industry

Leaving a job working on the BioShock series to make a game set entirely in a single house was a big gamble - but one that has undoubtedly paid off.

It's been five years since Steve Gaynor and his team at Fullbright released Gone Home, and the game's influence continues to be felt across the industry. And yet, as the studio's debut is nudged back into the spotlight with the release of the Switch version, Gaynor himself still has trouble processing just how that influence came about.

"We didn't think it would go beyond the group of people it was made for, people who just wanted a story game," he tells GamesIndustry.biz. "But upon release the critical reception was a lot more effusive than we could have imagined. The public reception, the attention the game got and the conversations it started... you can't ever really anticipate those things.

"We've been really grateful for the fact this little game we made in our basement could reach a lot of people and affect a lot of their outlook on what games could do. We've been really fortunate to see a lot of people who had never made a game before played Gone Home and was part of them thinking they could make games. We've seen influence in smaller games, bigger games and that's been really cool.

"Knowing that we made something that really contributed to how people thought and talked about what they were doing, and what we do as an industry, has been really cool."

Gone Home remains one of the exemplary exploration games, a point of reference to convey how an upcoming indie project might play. The phrase 'like Gone Home but...' is not uncommon in media coverage now, and yet when it released it was unusual for a first-person title to be completely devoid of action.

Gaynor and his team were inspired not only by their own backgrounds working on games like BioShock, but other immersive sims like those of Looking Glass Studios - "the idea of putting the player in an immersive state that felt lived in, that you could understand the lives of the people who had occupied these environments from what you found and from inhabiting those spaces".

"Gone Home was part of a moment of being able to give people confidence to make things, or part of bigger things, that really could say this is just about the story"

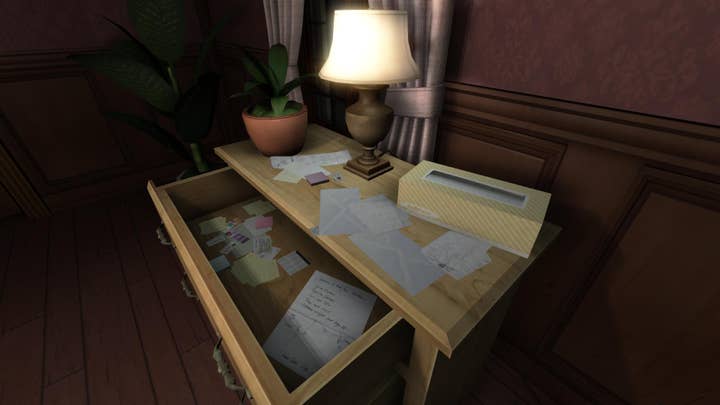

The result was Gone Home, a title in which you play a girl returning to her family's house after a trip away to find it abandoned. Only by exploring the house and investigating do you discover what transpired.

For this debut project, Fullbright was determined to explore the possibility of not just building a game with strong environmental storytelling, but making it the core of the entire experience. Today, Gaynor observes that titles like Firewatch and even sections of AAA games are taking this concept further in their own way.

"I think Gone Home was part of a moment of being able to give people confidence to make things, or part of bigger things, that really could say this is just about the story, just about being there, and that players can engage with that and be excited about it in and of itself," he says.

"That's an influence I'm really glad to have been some part of. I think it gives game developers more tools to be able to connect with players about characters and life experiences that are expressed through being in these places. I would rather people have more ability and more ways to tell a story through play, and I'm always looking for other people bringing exciting things to that space."

Making such a seemingly passive playing experience compelling is perhaps the toughest balance to strike. Fortunately, Gone Home benefits from Gaynor's time as a level designer on the BioShock games, where he learned how to "use the environment to guide players and communicate with them" in a way that still lets them explore at their own pace but ensures they aren't wandering aimlessly.

Concepts and tools like gating, lighting and the way spaces are laid out could be used to imply where important discoveries might be, hint at where players must venture next, or remind them of an area they've passed by yet to explore. The trick was to "feed the story along an unspoken path" and balance what and how much players might find in each room.

"Everyone has a story that's incredibly important to them. Not because it's world-ending and unbelievably dramatic, but because it happened to them and people they care about"

"The house in Gone Home is very much laid out the way I would lay out a BioShock level, in this kind of hub and spoke shape that's gradually unlocking," Gaynor explains. "But when you go into a room it's not a combat encounter; it's a place for you to find things.

"We used all these subconscious design and player direction tools to make it hard for the player to miss the important stuff, but also reward them for digging into the corners and trying to find every single thing they can. That's very traditional level design stuff, it's fundamentals, but it was applied to a player experience that was unique compared to where I had learned those skills - but they translated very well."

This plays into another core concept that Gone Home explored: allowing players to discover the story for themselves. While not the first game to do so, the game's detailed environments are a prominent example of developers shifting the storytelling power to the player - again, achieved through those level design tools.

A newspaper clipping here or a receipt there can reveal more about the characters that left them, but Gaynor was keen to give players direct involvement in how the story could be interpreted - unlike books or movies where multiple people receive the same information in the same order, Gone Home opened itself to playthroughs where not everyone discovered all of its secrets and thus had their own views on what happened.

"Gone Home is definitely the defining game of our studio, and of my career, and I hope it will lead to us being able to release a lot more interesting games going forward"

Gaynor was also keen that the story be simple and more down to earth than the AAA blockbusters he was used to developing.

"If you just wrote out the plot of Gone Home it would be a very simple story, but what we wanted to do was say everyone has a story that's incredibly important to them," he says. "And the reason it's important isn't because it's world-ending and unbelievably dramatic, it's because it happened to them and to people that they care about.

"Being able to say you're going to care about this story because the game gives you a way to care about the characters like they're someone you know, not because the fate of the world hangs in the balance or any other dramatic element, is something that your involvement and presence in the place where it's happening, being part of how this story is exposed to you really helps forge that connection."

It's impossible to discuss Gone Home without touching upon that story and it's most ambitious aspect. As players explore the house, they soon learn the family's disappearance stems from their younger sister coming out as a lesbian and the divide it created among her relatives.

It's a brave and very real topic to explore, one that few video games had ever touched upon in such a sensitive way. But Gaynor recalls it was not decided upon in some grand, agenda-setting motion, but rather a more mechanical storytelling process.

"Our starting point was we wanted to make a game that was just about being in a place and exploring a place, finding out about the people who lived there," he says. "We were a small team, on a small budget, so what could we actually build that would support that kind of experience?"

A family home made perfect sense, a place where the lives of multiple people is evident all around. Fullbright wanted Gone Home to be a contemporary story, although chose to set the game in the '90s to open up possibilities for more written documents around the house - "we didn't want people to have cellphones and email." With the setting established, the team began brainstorming the types of conflicts that would play out within a family's house.

"Knowing that we made something that really contributed to how people thought and talked about what they were doing and what we do as an industry has been really cool"

"It had to be a conflict that was in the family itself, so we start talking about what if the child of the family fell in love with someone they weren't supposed to, what if it was a Romeo and Juliet kind of thing - but a modern version," Gaynor says. "We arrived at Sam being a queer character coming to grips with how that part of herself meeting her family and society at large would affect her, and how she would navigate that.

"We procedurally arrived at what we determined our fictional premise would be, and at that point I realised I'd just signed up to write well out of my own personal experience. It was still valuable and worthwhile to pursue, but you have to take it really seriously and not just assume that you know enough to do a thing just because you want to."

Gaynor set about reading blog posts, fiction and non-fiction that dealt with women's coming out stories, as well as interviewing people in his own life that had grown up with these experiences. Critics agree the effort and attention to authenticity paid off, with Gaynor doing justice to his chosen topic - and the designer is pleased to see he has not been alone in exploring such an important aspect of life.

"We're seeing it in big games and small games," he says. "We're seeing what Naughty Dog is doing in The Last of Us II, where they're not shying away from the main character being a queer woman. I love a lot of small indie games that are going all in on this - I love Butterfly Soup, which is just a fantastic, purely story-driven visual novel about a bunch of queer teenage girls that love baseball. It's really funny, and it's exactly like it is. Same with Dream Daddy, a game about gay dads dating each other - that's what the game is. It's not a side part of the game, or something that's alluded to, it's what the game is.

"I think seeing games have that confidence and ability to say, 'this is going to be the whole thing, not just part of it', it's really exciting to see. It would definitely be great to see even more games take a true focus on characters that aren't the ones we usually have access to, and I hope we'll see more of that."

Following the success of Gone Home, Gaynor and his team moved on to sci-fi exploration and adventure game Tacoma, which also received rave reviews but didn't quite match the excitement around his debut independent title. And Gaynor is absolutely fine with that.

"You can't ask for anything more than to have one of your early projects connect with people, move people and be something that people care about at all five years on," he says. "That's a rare thing in and of itself.

"For me, Gone Home's success is the thing that has allowed me to continue doing this as a job in the way that I want to: running our own studio and making stuff we believe in for its own sake. I don't expect anything that I make in the future to have anything like the impact Gone Home had. Most people don't get to release one game that this many people care about, and I think it's probably folly to get greedy and hope you get to have that twice.

"Gone Home is definitely the defining game of our studio, and of my career, and I hope it will lead to us being able to release a lot more interesting games going forward."