Indies on Steam are betting on discoverability

After a year of missteps by Valve, indie devs are cautious about Steam Labs and their future visibility on Steam

It's been a rough year for indies on Steam.

To be fair, many of the 12 indie developers I've spoken to over the last six months might gently rap on my window and inform me that, no, it's been a rough several years for indies on Steam. But the last year has been especially rocky thanks to a series of discoverability and communication missteps that have left many independent developers feeling ignored at best or deliberately hamstrung at worst.

For example, a sudden, unexplained change in Steam's algorithm in October caused sharp traffic drops for many. And just a few weeks ago, confusion about the Steam Summer Sale resulted in indie games being removed en masse from users' wishlists -- a critical feature for indies.

That doesn't touch on several other events from the last year that directly affected -- or at least demoralized -- smaller developers. Some of these included a threatened takedown of some indie games due to supposed "pornographic content," a vague new content policy, web API adjustments that hurt Steam Spy and made helpful data less accessible to indies, and new revenue sharing tiers that only benefit games that are already best-sellers.

"Steam gives you a bare minimum package now"

Tom-Ivar Arntzen

It's easy to see how all of this in the scope of a year could be disheartening for a small developer, especially one struggling to get noticed on gaming's largest PC storefront. And most of the developers I spoke with acknowledged that the basic challenge of discoverability when there are just too many video games isn't Valve's fault. Valve has the unenviable problem of figuring out how to categorize tens of thousands of games so users can find and buy what they wanted while still giving deserving games necessary visibility.

However, many of those same developers also expressed frustration that, while in the early days of Steam Greenlight there were numerous benefits to having a game appear on the platform, those benefits have largely dissolved as the library of games has exploded. They say Steam's decision to rely on a changing algorithm rather than curation has hindered rather than helped their games, resulting in steep drops in traffic, unpredictable game sales, and an increase in the amount of time and expense needed for marketing that had not been as critical when Steam was a smaller, more curated platform.

"Steam gives you a bare minimum package now," said Tom-Ivar Arntzen of Tinimations, developer of Klang. "It's not anything at all. When the indie movement started out, that wasn't the case. If you actually made it to Steam, you got some exposure for that. Being on Steam gave you bragging rights."

Several developers, including Megan Fox of Glass Bottom Games and Emma Maassen of Kitsune Games, told me that many previously successful indie studios are beginning to "hedge" against the probable decrease in attention their new games will receive by planning in advance to put more resources into marketing than were necessary in the past. Maassen remembered forecasting 10,000 unit sales for Kitsune's MidBoss back in 2017, but it did half that number. At first glance, that might be chalked up to something the studio did wrong, but she said that when she looked at Steam Spy and spoke to other indie developers, they reported a similar halving of visibility for anyone not already at the top during that period.

Fox noted that while her upcoming game, Skatebird, looks poised to do quite well for an indie, that's because of traffic the studio brought in from outside campaigns.

"As it stands it's pretty much all 'our' traffic, but with the numbers we're pushing in, come launch, we'll most likely be above whatever line it is where Steam's newer algorithmic stuff kicks in," she said. "Cool for us, sure, but doesn't really help anyone else affected."

"It's very demoralizing for small teams to have a graph tell them that a thousand people don't care about their game anymore"

Max Cahill

Last October's algorithm shift was the breaking point for many developers to begin voicing their frustrations publicly. Multiple developers I spoke to said that similar sudden drops in traffic with no explanation had happened before, but the one in October seemed to be the most widespread and dramatic. After that blow, it's no wonder that the Steam Summer Sale's wishlist misunderstanding went over the way it did.

"The major effect I've seen is that it's very demoralizing for small teams to have a graph tell them that a thousand people don't care about their game anymore, especially during a time that's supposed to bring them more money," said Max Cahill, developer of King Arthur's Gold. "Valve really hasn't made any real amends to the affected folks as far as I know. They released a clarifying post about how the sale worked but the damage was already done; no one is going to go re-wishlist an indie game that they axed to try to save themselves a few bucks."

Cahill's lament that Valve hadn't "made amends" is the other common thread throughout every major incident that had an impact on indies in the last year. A number of developers are fed up with what they see as a lack of communication from the company. Games are warned or removed from Steam, the already-mysterious algorithm is changed, the rules of a promotion aren't made clear, and they aren't told what's happening.

One developer who asked to remain anonymous told me they attended a GDC meeting for indie developers to speak to Valve representatives as a sort of "damage control" following the algorithm issues in 2018. However, they said that the meeting ended up being more condescending than anything: "It felt like parents telling kids why they have to eat their vegetables."

At one point during the meeting, developers asked if they could have some kind of guide or checklist of what Steam was looking for in a game for it to be promoted and given more visibility. According to the anonymous developer, Valve's response was: "If we gave you that checklist, you would use it."

That response might be insulting to some developers, but Jonathan Hanna of SuperSixStudios understands why Valve would resort to it.

"Let's say your game is more discoverable the more you update the game," he said. "Well, then people are going to put out lots of tiny patches over and over again and no one's going to benefit from that. Same thing with writing updates. If you write an update often, does that increase your discovery? If people know it does, they'll just write a bunch of updates to try to get back on Discovery Queue. People are already doing that with release date. You put the release date out and then you're in Upcoming Games, then right before the release date you change it, and you do it every 30 days. The players aren't benefiting from that. Steam isn't benefiting from that.

"So I kind of understand. I'm not asking them to give me the algorithm. I just want to know if something changed, and for them to give me a sort of really high-level overview of what gets a game on the Discovery Queue and various other pages and things that can get it discovered by players. But I'd be shocked if they ever shared the exact data. It's already being abused."

"I'd be shocked if they ever shared the exact data. It's already being abused"

Jonathan Hanna

Some developers are lucky enough to have a Valve representative they can speak to directly, who might be able to provide some of the answers Hanna mentions. But how specifically one gets one of those seems to be a matter of confusion among many I spoke to, and some have never spoken to anyone from the company directly at all. A few developers told me that their posts with concerns on the Steam developer boards are often ignored entirely, and there's no clear avenue to go down if you need assistance.

"We have had no help, no guidance, love or support," said MidBoss CEO Cade Peterson. "It's a black box they operate in, and I get that at such a size they are now it's probably impossible to do more, but every major change they've made in the past four to five years has been at the cost of helping developers and pretty much every new change has hurt them."

The picture doesn't seem optimistic, but there is evidence things may be improving slightly. Some developers saw their traffic return to normal after Valve responded to the issues with the algorithm. Some reported surprise successes during the Steam Summer Sale despite wishlist frustrations. The Epic Games store, though still closed off to most developers, appears to have challenged Steam sufficiently that Valve is re-examining things like revenue share and recommendation. And everyone I talked to was at least cautiously optimistic about a brand new feature announced last week, Steam Labs.

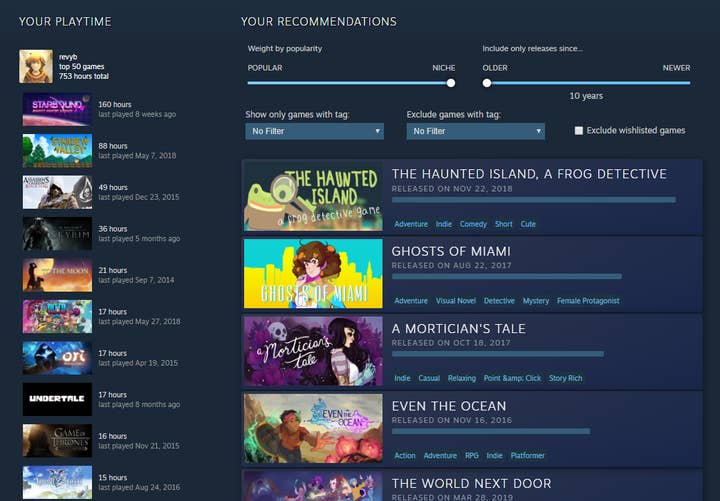

Steam Labs is an experimental area on the storefront where Valve is currently testing new discoverability features. There are currently three available to play with, two that involve short trailers and the most interesting of which is a new take on game recommendation that uses machine learning to suggest titles based on what the user has played in the past.

The Interactive Recommender has some drawbacks, such as a potential bias toward genres with longer playtimes and games with high replayability, and the fact that if you've left a game idle for hours on end it will skew your data. But in general, indies seem to feel it's a good first step toward getting visibility, giving users what they want, and being clearer about how those two things happened in the first place.

"There are so many awesome games that don't get to be that 'next hit' -- they might resonate with a smaller niche of people, they might never quite make it through all the noise, or just have downright bad luck at launch," said Steve Filby of Motion Twin, when asked about Labs.

"So I feel like this tool, which seems to be able to dig down past the big hits and look into the mid-tiers and the super niche games will be really useful for getting those games more attention from potential fans. It doesn't seem to address the problem of getting your game noticed in the era of 150 games coming to Steam in a week, but at least Valve is aware of a discoverability problem and is trying to address it."

"You don't fight big powers directly; you cultivate new spaces and make wider bets"

Megan Fox

Philip Barclay, executive producer at Sabotage, was slightly more skeptical: "In the end, it really all depends on how good the recommendation algorithm is. Steam does have a huge sample of historical data to work with, but time is too precious for players to give a second chance after a bad, time-consuming game experience. Also, it could be an uphill battle against the recommendation algorithm's reputation of using cheap upsell tricks that rarely end up in positive purchases experiences."

The indie developers I spoke to earlier in the year about the algorithm issues also circled back and expressed optimism about the features, though they all said that more than anything they just want more clear communication with Valve on when things are changing, and how.

"Valve providing a human contact to coach and direct indies with their releases and coordinate a good time, price, and marketing approach would probably be the most practical thing they could do for small teams," said Cahill. "They are very hands-off even with teams that do have a specific contact; teams that don't [have a contact] get basically zero guidance on how to perform well on Steam. Having a human in the loop is incredibly important as the general advice isn't going to work for every game."

Some, including Fox, are encouraging indies not to abandon Steam, but to focus less on trying to make the behemoth shift and more on adapting to the changing indie landscape as a whole.

"Most indie devs have zero leverage right now," she said. "Even if we all left, Steam would function much as it always has, even if they'd miss us on a promotional or emotional level. You don't fight big powers directly; you cultivate new spaces and make wider bets. In literal terms right now, I mean stuff like itch, GOG, consoles, Game Pass, other stores paying for exclusives, mobile, AR, VR, local arts funding, and that's just off the top of my head.

"You 'win' against bigger players by being supported by your own wider community, where the big players need you more than you need them. Then you have leverage."