Spry Fox, Triple Town and the Clone Wars

Spry Fox co-founder David Edery discusses the harsh reality of copycat design, and what developers can do to protect their creativity

David Edery, co-founder of Spry Fox, claims that the speed with which clones of its popular casual games appear has been a chastening experience, softening the freewheeling spirit with which the company was founded.

In an exclusive interview with GamesIndustry International, Edery detailed the fallout from its experiences with copycat designers cloning successful Spry Fox games like Triple Town and Steam Birds.

"We're much less care-free than we used to be," he admitted. "We've learned some valuable lessons."

Ultimately, the company's founding principle of developing original games for digital platforms still stands, but key aspects of its approach to design have been changed by necessity.

"We want to make original games, and the only way to do that is to release early and release often, because otherwise you're just taking on way too much risk. Unless you're PopCap you can't afford to work on an original game for 5 years before you release it - if it fails that's just too much effort."

When Triple Town launched on Facebook and Google+, the company deliberately left out a number of key social features. Edery wanted to first see how popular the core gameplay mechanic would be with users, before introducing new features gradually.

As a creative strategy it makes sense, but Edery's experiences suggest that the increasingly cut-throat world of casual game design has made such a considered approach impossible.

"We purposely released the game early to see if people would think it was fun on Facebook and then add the social stuff in later," he says, "but then the clones just started to come out of nowhere really fast. We thought we'd have six months before the clones started knocking on the door, but it happened way faster than that.

"If you're going to release a social game make sure you have the viral stuff baked. Don't test the gameplay mechanic and add the social stuff later. Don't fix the ARPU later - no, make sure you have a decent ARPU right out of the gate."

"For a game like Triple Town our attitude is to assume that it will be cloned within two months"

Most importantly, an independent developer working on digital platforms needs to be able to roll-out a new game across as many devices as possible, as quickly as possible. Once a game starts to show commercial promise, the countdown to the first clones appearing is already well under way.

"That comes with a lot of technical constraints, but if I can release my original game and realise over the course of a month that it has potential, then a month later blast it out on mobile, blast it out on Steam, blast it out everywhere, great, I can stay ahead of my competitors. Gone are the days when I had the luxury of a year before someone tried to copy me.

"A game like [Spry Fox free-to-play MMO shooter] Realm Of The Mad God is so technically complicated that nobody can clone it very quickly, but for a game like Triple Town our attitude is to assume that it will be cloned within two months.

"If we're going to release a game, we're damn sure we can blow it up big within two months if we need to."

For Edery, that's is the key difference between the culture of cloning in the early days of the arcade and today: it's not a problem of quantity; it's a problem of time.

"It has never happened this fast. There were clones of Steam Birds within months. The first Triple Town clone was within weeks - super fast. That one wasn't very successful, but nevertheless: weeks."

He rolls the word around in his mouth. "Weeks."

Edery remains surprisingly amicable and composed throughout our interview, but there are moments where the sheer frustration of those moments that he discovered phantom products based on Spry Fox's work peek through his calm demeanour. He offers one such example that captures just how "bald-faced" the cloners can be.

"The night we launched Triple Town on Android market - literally the same night - kind of on a lark I decided to type 'Triple Town' into Android Market to see what came up - people will often use the title of another game as a keyword for their game, even if it's not all that similar - and Triple Town comes up.

"We had been working with Google so I wondered if they had done something that pre-prepared the market or something like that. It's my art, it's my everything; it's the game, but it's by some Chinese guy. He had literally uploaded our game.

"It has never happened this fast. There were clones of Steam Birds within months. The first Triple Town clone was within weeks"

"There you go. I mean, what the hell? I haven't talked to every game designer who was making arcade games 20 years ago, but I don't think anyone would have done that. Literally, my game, with my name, and my art."

Spry Fox was founded by Edery and Daniel Cook in September 2010. Edery was formerly worldwide games portfolio manager for Xbox Live, and Cook was a game designer at Microsoft Game Studios.

The intention was to build a creative company that functioned like a modern film studio, where teams are built and disbanded based on the specific requirements of each project. "We work together on what we love, and we part ways when our interests diverge," Edery said at the time.

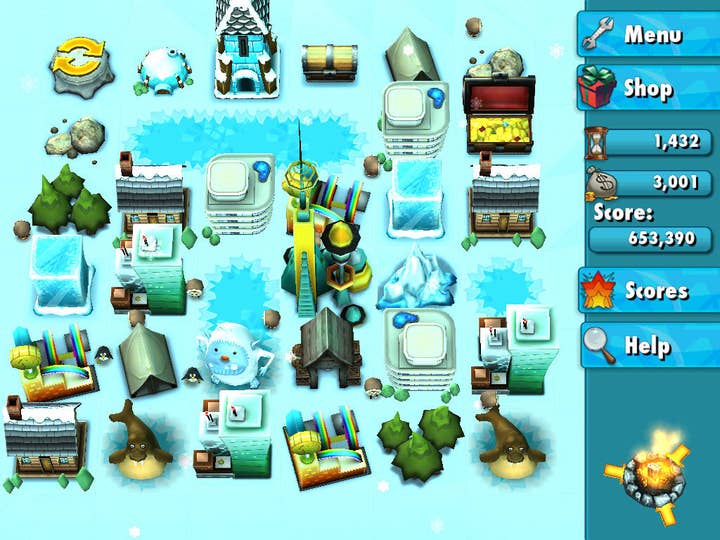

Spry Fox filed suit against the social publisher and developer 6waves Lolapps in January this year, citing similarities between Triple Town and 6waves' subsequent iOS title, Yeti Town.

In a post on the Spry Fox website, Edery revealed that the company had talked to 6waves Lolapps about publishing Triple Town on Facebook, giving it access to the game's closed beta and sensitive information regarding its business and monetisation strategies.

Spry Fox ultimately chose Playdom as Triple Town's Facebook publisher, but by that time Yeti Town had already been released on iOS.

"What most people don't know is that 6waves was in confidential (under NDA) negotiations with us to publish Triple Town at the exact same time that they were actively copying Triple Town," Edery wrote in a blog post.

"We gave 6waves private access to Triple Town when it was still in closed beta, months before the public was exposed to the game. We believed those negotiations were ongoing, and we continued to give private information to 6waves, until 6waves' executive director of business development sent us a message via Facebook on the day Yeti Town was published in which he suddenly broke off negotiations and apologised for the nasty situation."

6waves Lolapps subsequently denied breaching the NDA, and expressed "disappointment" in Edery's decision to take legal action. However, Edery insists - as he did at the time - that the choice was not taken lightly.

"If Angry Birds was released for the first time today by a studio without much marketing, would it succeed? Who the hell knows? Who knows"

As an enemy of creativity, cloning will have a more profound impact on independent companies, particularly in the more competitive landscape of contemporary mobile and social development. The gold-rush that defined the early days of iOS and Facebook development has long since finished, and there are now huge, entrenched players in both markets with the sort of resources to make each new release a success, if only for a brief time.

But for smaller studios desperately trying to get their products noticed every hit counts, and a single failure can be the difference between survival and collapse. For Edery, developing a breakout hit has become exponentially more difficult in the last few years, and looking to the more successful companies can be misleading. Very often, they benefited from a healthy does of pure good fortune.

"Zynga is what Zynga is today due to a combination of factors, but the most important factor is right place, right time," he says. "They just happened to be on Facebook at a time when you were able to spam and get a lot of users that way.

"Halfbrick and Rovio, when they made Fruit Ninja and Angry Birds, mobile was more of a meritocracy; if you made a good enough game and you got featured, there was a great chance that you could stay on the top of the charts for a period of time without spending a dime on marketing.

"If they hadn't made good games they wouldn't be where they are today, but at the same time it's viable to ask: if Angry Birds was released for the first time today by a studio without much marketing, would it succeed? And the answer is, 'Who the hell knows? Who knows.'"