Six ways to improve your world building

Kate Edwards gives developers advice and tools to build fully realised game worlds

Culturalisation is mostly known as the process of tailoring your game for a specific culture, beyond language translation. But it can do much more, as former IGDA director and Geogrify founder Kate Edwards highlighted in her Plan B Project talk last week, 'Building better worlds through game culturalisation'.

A lot of her presentation was dedicated to the reasons why culturalisation matters as much as localisation, and how to navigate sensitive themes so your game can reach a wider audience. However, it also contained useful advice on improving your approach to building game worlds.

"A lot of the worlds that we make as game developers are very complex," Edwards said. "Take something like Skyrim, which is very detailed, very realistic and yet it takes place in a completely fictional universe. Or things like Halo, which actually takes place in our universe but in the far future. It involves a lot of science fiction elements and imagining things the way they might be at the time. Even something like Super Smash Bros still has a world, still has an environment, still has a narrative.

"[There are also] games like Grand Theft Auto 5 and this is the kind of world that I would call hyperreal. So it's almost Los Angeles but it's not quite Los Angeles. It's Los Santos, but they did such a remarkable job of recreating the vibe of LA as the basis for their world building."

All these games have something in common: they use certain tricks to make the player believe that there is a larger universe beyond what they can see in the game.

Understanding the core aspects of world building

Setting the context of your game, thinking about its complexity and the structure of its world, are all key aspects to world building, and the first questions you should ask yourself.

"We've got the real world and we've got fictional worlds, and then of course we have this broad zone of overlap in between," Edwards said. "It is never black and white. You often have games that are purely fictional because the narrative demands it, and you've got others that are completely in the real world, but they might be in a different time or somewhere in the middle.

"This is important because it does matter in terms of culturalisation decisions. If you're setting your game in the real world and using real geography with real culture and history, you have a different set of rules you have to follow."

“The realisation goals basically set out how much of the world you actually need to make”

Edwards is talking about the realisation of your world -- not to be mistaken with the realism of your game, she pointed out.

"Realism is a design decision -- how realistic they want [the game] to look. Realisation is the combination of the narrative goals of your game and its experience goals. So what's the story behind the game and what is the player actually doing in your game? That's the most basic level to define; what your realisation goals are. The realisation goals basically set out how much of the world you actually need to make, and that's really important."

From there, there are structural tools you can use for realising your world and making your game's setting believable, by making it feel like it belongs to a larger universe, even when that larger world is never seen.

Build world familiarity with thematic layers

There are thematic layers that you can use when creating a world that will make it feel more complete. Edwards pointed out that this list could include many more levels of details, depending on the type of universe you're building.

- Climatology and atmosphere

- Geophysics

- Biosphere

- Demographics (species, genders, ages, ethnicities)

- Cultural identities (language, history/lore, symbology)

- Cultural systems (faith, politics, economy, transportation)

However, be careful about how you use these layers -- ideally, they need to add to the narrative in a meaningful way.

"A game like Breath of the Wild, the climate system is directly impacting the gameplay," Edwards said. "You're running around in the mountains, you get zapped with lightning, you freeze. When they decided to put a weather system in the game, it actually made sense because it all has a direct impact on the narrative and on the experience. Now, I've seen other games where they built a weather system, but it really doesn't do anything. It's just there for atmospheric purposes.

"Now, that's okay, but my warning to you, and the reason I bring up the layer approach, is to think very carefully about what layers you need to realise the game. I would recommend you start with that. Most games are going to need some kind of actual geography like landforms, but maybe not [yours].

"So you have to think very hard about what exactly [is] the most minimal version of the world to serve the experience and narrative goals [of your game]. And then, if you at least get that far, then you can make decisions [about] whether or not you want to add additional layers that might enhance the visuals, that might enhance the environmental appeal, but I would not go there until you've actually at least satisfied the most basic realisation needs."

Rely on maps and languages

This may sound like common sense, but maps and languages are both crucial steps to making a world feel alive.

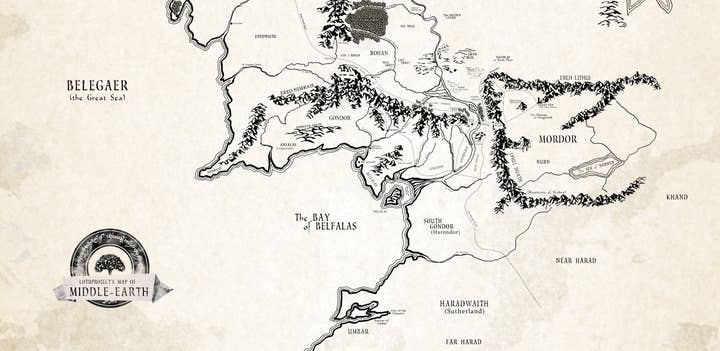

"I think the inspiration for a lot of us came from JRR Tolkien," Edwards said. "What he did in his world building process [was] using his core strength, which was language. And so he was able to create languages like Elvish and Dwarfish, and he used [them] as a basis for creating a culture around that language, which then populated this world."

A great example of a game language that led to a realised world is Simlish, the language invented for The Sims. While it may sound like gibberish there's actually some logic to it, which you can read about in this excellent article on TechRadar. It all participates in making the player feel like their character is part of a wider world.

No one is expecting you to create a new language every time you develop a game, but you can achieve a sense of belonging to a culture by using specific expressions, dialects or accents. Tolkien also enhanced this feeling by creating geography in his world by using a map, which is a common trope in fantasy.

"There's a lot of maps that get created for fantasy works and it's often the author's way of solidifying the reality of the world that they created. We respond to maps as being factual, we see them as being something like an artifact of actual exploration and research. So for a lot of authors, when they create a map, it's their way of saying: I was there, I went to this place, and now the story that you're going to read is basically the story that I saw first-hand when I was there.

"It's an interesting notion, and using maps in that way often gives a certain sense of reality that you would not get if you didn't have the map there to illustrate the world and the context of the world."

Build cultural evidence

Cultural evidence is another strong tool to create a fully-realised world, and it's essentially the process of "making stuff," Edwards explained.

"You're past the concept phase and now you're basically letting loose all the fantastic creative people on your team. But what happens often during this phase is that people over-create and/or they just build environments and throw all kinds of stuff in there -- objects, symbols, banners. They just dress up the world and make it look lived in."

However, if you want your game's world to be cohesive and well realised, you need to think carefully about how it's populated.

“Don't be lazy with creativity. You need to always create with a purpose”

"Don't be lazy with creativity," Edwards continued. "Don't just create stuff because you can. You need to always create with a purpose. So when you're creating an object and throwing it in the environment you need to think: Why is this going into the environment? What does it mean? What relevance does it have to the narrative and all the other things that are going on? Not everything always has to have a direct relationship to the player, but it still should be created with a purpose, not just kind of thrown in there because you're trying to rush down a checklist that some manager gave you."

She also pointed out that someone in the team should always ask artists those challenging questions.

"Somebody should ask: what does that mean? Where did that come from? What was your inspiration? Now you don't have to question everything, but I'm saying sometimes having that meta level of question really helps, not only the creators to step back from what they did and think about what they actually created, but also to catch things that may be potentially problematic later on."

Ensure logical consistency

Not only should the cultural evidence you're building make sense for the universe you're creating, but everything should be logically consistent with the design of the world.

"We have logical rules that exist and they apply to everything that's within the world," Edwards said. "Why is this important? Because, even within Tolkien's universe for example, much of his universe is built on real world rules -- rules of gravity, geomorphology, hydrology. Even when he adds things into his narrative, like magic for example, the way that magic is used has to have a sense of logical consistency. Only certain people can [use magic] and only at certain times do they evoke that power for certain reasons.

"Those are rules. If you have something in a game, whether it's something fantasy or bizarre or whatever, it still should be rooted in some kind of logical rule. We want to make sure that when we're creating things there's not a contradiction either between the narrative intent that we have and the narrative experience, or the content that's in the world."

Edwards took the example of Kameo, a 2005 game developed by Rare that she worked on. This completely fictional universe that has nothing to do with our world featured symbols that resembled Christian crosses. When Edwards questioned what they were supposed to be, the artist said they were grave markers.

"That's interesting because there's no Christianity in this universe of Kameo, so why would they be using wooden crosses? That doesn't make any sense. At the time, the answer I got from the artist was: 'What else would I use?' And I'm like: maybe create a grave marker that fits the narrative of the Kameo universe?"

Imply complex systems

In order to imply complex systems in your world, you need to create connections between characters, locations, architecture -- you need to imply lore, without necessarily building it.

"This is a concept that a lot of narratives use to basically convey the sense of a much larger world," Edwards said. "You can mention something without having to fully explain it or to go into depth about it, but you've made a connection. And to make that connection is all you need to do so you can convey a much bigger sense of a universe without actually building that universe. "

All it takes is an interaction with a book or an object in-game that explains some lore for instance. Edwards took the example of Halo: Combat Evolved to explain the concept.

"You're running around in this environment, and you're seeing this really interesting architecture that was made by the Forerunners [an alien species in Halo]-- I remember in that original game a lot of us were really fascinated by the story behind this ring. Why does it exist and who are these people? The core narrative the game gives very little evidence about who the Forerunners are and what happened on this ring, but the game [had] these things called the terminals, and if you interact with them, up would pop a screen and it would give you a whole sense of backstory as to what was going on in this world.

"So just by doing that one thing, one point of interaction, you click on it, you read something, all of a sudden you've expanded the narrative of the world. You didn't have to build a whole other level, you didn't have to build a whole bunch of other characters, you basically were able to open a little window into a broader narrative around the universe you created."

The GamesIndustry.biz Academy guides to making games cover a wide range of topics, from finding the right game engine to applying for Video Games Tax Relief, to tips for making a cross-platform game, or even how Ori and the Will of the Wisps was built with 80 people working from home. Have a browse.