Rami Ismail's top ten tips on surviving the indiepocalypse

The indie veteran offers studios advice on how to stand out and thrive in an increasingly competitive industry

The indiepocalypse has been discussed at length over the last few years. It's the idea that there are so many indie games available on the market that it becomes unsustainable.

Indie consultant Rami Ismail (co-founder of the late Vlambeer) discussed this at length during a talk at this year's Reboot Develop Blue conference in Croatia.

Ismail observed that the number of indie games has drastically increased in recent years, making it also incredibly difficult to get published.

"[The indiepocalypse] is the belief that if this trend continues, with the increased amount of supply, eventually indie games as a market segment will just die," he explained. "I've seen some segments of the industry die – Flash games, Facebook games – but here's the thing: the bad news is that you kind of don't stand a chance of making a hit game if you're an indie. The chances of making an Among Us, a Minecraft or a Hades are fairly small.

"So what can we do? What's the solution? You stand out, you survive and thrive. How do you do that in 2023?"

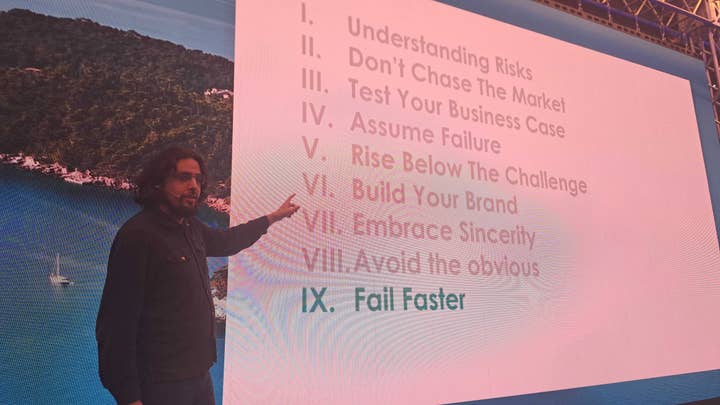

- 1. Understand risks

- 2. Don't chase the market

- 3. Test your business case

- 4. Assume failure

- 5. Don't aim too high

- 6. Build your brand

- 7. Embrace sincerity

- 8. Avoid the obvious

- 9. Fail faster

- 10. Be luckier

- 11. There is no indiepocalypse

1. Understand risks

Ismail observed that there are primarily two ways of running any business : you either minimise your risk or maximise your opportunity. Even if you do both, one will be more prominent than the other.

"If you have an infinite amount of money, please go and maximise your opportunities. You can take risks. But if you're just starting out, your biggest obstacles are probably that you haven't shipped anything, you have no money, and you have no experience. At that point, you should figure out how to minimise your risks."

"The best way to minimise your risk is just to get to the point where you can ship something"

Ismail advised that studios start by making a game that's not expensive. He shared that Radical Fishing – the original Flash version of what became Ridiculous Fishing, Vlambeer's biggest hit – cost around $60 and was made on school computers.

Nowadays, indie budgets are much higher, with Ismail giving the ballpark figure of $70,000, although he did not detail what this would encompass. He noted that some publishers will only consider games with a budget of $1 million or more.

"The best way to minimise your risk is just to get to the point where you can ship something. The problem with budgets being $70,000 or more is you need to get somebody to pay for it, because if you're paying for all of that, you're spending three years of your life and money that is probably not going to work.

"When I talk about risk, what I mean is you want to move as much of the risk away from you, as fast as you can."

2. Don't chase the market

After expressing exasperation at the number of indies who tell him they're making roguelikes, Ismail urged developers to do something different. While building on other people's success may seem to make sense, it's hard to compete with established hits and it's impossible to know what the next hit will be.

"In the games industry, things move in waves but they're also weirdly unpredictable," Ismail said, reminding the audience that Overwatch's success in 2016, a hero shooter, couldn't predict that the biggest hit two years later would be a narrative-driven God of War.

"There's no rhyme or reason to this. Did anybody predict that a game about little squishy people backstabbing each other on a space station [Among Us] would probably be the defining game of the past five years of indie games? That there would be political discussions about it? Of course not."

Ismail added that the larger companies who can chase the market can only do so because they have access to a "staggering amount of data," for which they pay tens of thousands of dollars. And even if indies think they've identified a gap in the market, other studios probably have too.

"Don't chase the gap in the market, there is no gap in the market," he said.

"If you run a business, you want to look at the market, understand what's happening in the market. But you can't let the market lead your creative process."

3. Test your business case

Since indies are most likely going to be pitching to publishers and investors for funding, they need to test their business case. For this, Ismail recommended to start pitching with "the five publishers you hate the most."

"Don't go to your favourite publishers, because you want the best version of your pitch for them. Find the five you really don't like and just pitch to them. If they say, 'yes, we'll give you $10 million,' take the money. Fuck it, make the game, get it out there. But find the five you don't like and practise your pitch on them.

"Then pick the five you like slightly more and pitch to them. So many indies go to their favourite publishers with the worst version of their pitch."

"Don't chase the gap in the market, there is no gap in the market"

If you're self-publishing, there are still ways to test your business case. Put a teaser page for the game online, start talking about what you're working with to your potential audience.

"Put it out there, test it, iterate," Ismail said. "Trying to do the perfect version out of the gate never works."

He cautioned that any studios seeking publisher funding or support should stay away from the public until all else has failed.

"If you go to 100 publishers and they all say, 'This is the worst shit I've ever seen' then you go to an audience and they love it, they're not going to know 100 publishers turned it down. If you try a Kickstarter and fail, then go to a publisher, they won't be interested."

4. Assume failure

The only healthy way to run any business, Ismail said, is to assume that at the end of everything, your game doesn't make any money. This should also inform how you make crucial decisions about your business.

For example, when seeking funding from a publisher, make sure you ask for enough not only to make the game and ship it, but to also keep the studio running for three to six months, enabling you to get ready to pitch your next game.

"Even if your game is successful, you don't get the money at launch. It takes three to six months to hit your bank account. You want to make sure you have some runway at the end of your game, enough to get going on a new thing."

5. Don't aim too high

Ismail observed that most of the studios he knows rise to the challenge they face. The problem is the challenge will always grow based on what you can do.

He used his former studio Vlambeer as an example. The team was never bigger than seven people, and most of the time it was two to five people. So they only made games that could be made by two to five people.

"We made a deal when we started that we [would] never grow, and it worked out just fine because the games we were making were consistent with what we could do.

"As soon as you hire another artist, you then have to feed that artist, which means you need to make slightly bigger games with slighter bigger budgets," he continued, explaining that it then has a snowball effect, with new hires leading to bigger games leading to new hires, and so on.

"Just make better games," he said. "You don't have to grow to do that. Your team is getting better, getting more experience, more used to each other. Eventually your team starts being better without having to grow.

"Growth needs to be intentional, and if you're going to continue to rise to the challenge, you're going to lose control of that. So don't rise to the challenge, rise to slightly below it and stay there. Don't grow your studio past that. If you want to make bigger games, you can grow a little, but keep in mind any growth might cause additional growth."

6. Build your brand

While some may balk at the term 'brand,' games developers need to establish a human connection with their audience, Ismail explained, and build an identity that makes them stand out. He challenged developers to imagine two friends talking about their games in the future: what do you want them to say?

He also emphasised that this does not mean developers need to keep making games in the same genre. Vlambeer's games were all wildly different; the consistent identity was the use of guns and screenshake, something Ismail said the studio became primarily known for.

"People would play those games and go, 'Oh, yeah, that's a Vlambeer game.' They had a specific type of humour, they were kind of dark, kind of weird, had screenshake, and our audience identified with that."

An obstacle here is that publishers are also focusing on promoting their own brands. Ismail asked attendees if they could name the developers behind Cult of the Lamb or Hotline Miami. Few in the room could, but most knew the publisher was Devolver Digital – because the publisher has done such a good job of building its brand. Raw Fury and Annapurna Interactive were also cited as examples; people know what sort of games they release, even though they don't actually make games themselves.

"One of the things I find really distressing is the amount of people pitching to me, going 'We're making a game that's perfect for Annapurna.' Why are you making a game for one publisher? What if they say no? Don't make your game for a publisher, make it because you want to make it. There's something valuable there, and if you do that, you build your brand."

Ismail added that your brand is not just about your games. Community management and how you interact with your audience, how you talk to people within the industry and make connections – these are all important elements of building a brand.

"Every game has the fingerprint of its creator"

"It's not just your studio, it's also you. If you meet interesting people, be nice. Talk to people. Don't just talk to them because they could be useful to you, talk to them because they're people.

"As you grow in this field, you can help each other out every now and then. Not because you have to, but because they're nice people and we'd like to see nice people do well in this industry. If someone is successful, celebrate that. Do you know how hard it is to be successful? Celebrate people's wins. And when people fail, give them a quick phone call."

The key to building a brand is consistency, Ismail added, emphasising again that this doesn't mean sameness, but showing that people can rely on you for something, whether it's you as a person, your games, or your studio.

7. Embrace sincerity

Being sincere as an individual is crucial to being seen as reliable, Ismail explained. Despite all the things developers have in common, their life experiences are all unique.

"Every game has the fingerprint of its creator," he said.

He gave the example of war games, observing that a lot of these are made in the US and see players go to a foreign country or planet, shoot lots of bad guys in the name of liberating that place, with barely any consequences. He argued that the US is the only culture that would make games like that.

By contrast, Ismail mentioned titles like Spec Ops: The Line, from German studio Yager – a title about the hurt, guilt and shame of war – and This War of Mine from Polish developer 11 Bit Studios, a game about surviving the effects of war.

"Those two games were only so different because they were genuine. The teams didn't go 'We want to make a war game, what's the popular thing about war?' No, they have their own life experience, they thought about their grandparents' experience, and did something with that. Something new, something interesting. If you start looking at games as the inspiration for your games, you're going to make games like games."

He continued: "Creativity is a result of who you are. It's not an intentional effort to distinguish yourself. A lot of people think, 'How can I be creative by being different?' Stop that. What comes naturally to you? What is the thing that flows out of you, whether you want to or not? The more you let that be, the harder it will be for other people to compete with you, and the more chance you have to stand out."

8. Avoid the obvious

Obvious game ideas are the ones to avoid, Ismail warned. As mentioned earlier, most people will come to the same conclusions when exposed to the same challenges, which is partly why we see waves of similar games released. But relating the obvious ideas to your life, thinking about deeper connections and connotations, can help you come up with something truly original.

Ismail cited advice he was given at a game jam in years past: throw away the first three ideas. The example he gave was if a team was tasked with making a game around the theme 'extinction,' most people instantly start thinking about ideas around dinosaurs or meteors.

9. Fail faster

In Ismail's experience, some studios take a year or more to realise their game isn't going to work the way they hoped. This is why he stressed the importance of prototyping – but asked developers to think more carefully about what they consider a prototype.

"One developer showed me a prototype that was a bunch of sketched papers and a shitty thing that crashed every 30 seconds," he said. "But in those 30 seconds you can figure out there's an abundance of fun. Other indies show me prototypes that look like a finished video game. They had a main menu. All you need is a reset button for when it crashes."

He urged developers to "fail faster," to "stop being good game developers" and build prototypes that may seem rubbish but help you work out if the core idea for your project is going to resonate with players. Ismail recognised this will jar with some developers, but likened it to an artist being asked for sketches who worry they won't look good or a narrative designer asked for a half-page draft who says there won't be room for backstory.

"It doesn't matter. Don't get it right, just get it going. Make it bad, really fast."

He continued: "If you spend a year and half of your life working on something before you get to the point where you can ask someone if it's good, you've fucked up. You want to be able to go to [someone] three or six months in, show them the original sketch, the prototype, five mockups of how it's going to look, the story, the budget, the timeline, [and ask] 'Is this interesting?' A lot of publishers will say to come back with a vertical slice, and you know what that means? It means they're at least interested in it."

10. Be luckier

"Finally, the biggest tip is to be more lucky," Ismail smiled. "Just stop being unlucky! The honest reality of game development is even if you get everything right, it's a coin flip."

"Don't get it right, just get it going. Make it bad, really fast"

He pointed to his own career. Students in the Netherlands need to mail two letters to get into university, and he failed to send the second one. This meant he spent a year working at a retail store, where he learned salesmanship, and started studying a year later – by chance, the same year as Vlambeer co-founder Jan Willem Nijman.

"My career is entirely based on the fact that I suck at mailing things," he said.

"A lot of things in games are not about making the hit or getting it right, a lot of it is luck. Anyone who tells you otherwise is bullshitting. There are people who will never have luck, and that might be you. And there are people who will get lucky on their first try, and that might also be you. You can't control this, all you can do is your best… The only things you can control are consistency and getting to a point where you can ship. Keep doing that as long as you can, and that will minimise your risk. You minimise your risk until you reach the point where you don't have to. You keep your day job until you earn enough money to quit."

11. There is no indiepocalypse

Concluding his talk, Ismail shared that he actually thinks that the entire concept of the indiepocalypse is "bullshit." Fears about the indie sector based on the rising number of games released every year are based on the misconception that this number will continue to rise indefinitely. Ismail argued that it won't. While there will be more developers out there, others will quit or shut down.

"It evens out. There's a ceiling," he said. "The point about the market saturating? We've already hit that. There's already way more games than there is time for players to play. We're done, the market is full.

"More indie games developers than ever will fail. But that's also because there's more game developers than ever and there's more successes than ever. There's more people who just continue to make games."

He observed that it's the same in any other form of entertainment where people can independently publish and distribute their work. The key is to rein in your expectations and focus on the task at hand.

"You're not going to be the next Notch or Among Us, and if that's your goal, you will always fail," he said. "If you aim to just make your next thing, ship the thing, and then the next, and then the next, and you build that consistency, and you build that brand, and you build that audience, and you get it funded by someone else so even if you fail, you can try again… That's how you survive the indiepocalypse."

More GamesIndustry.biz Academy guides to Selling Games

Our guides cover various aspects of the development and publishing process, whether you're a young game developer about to start a new project or an industry veteran: