Positech Games: An Indiepocalypse survival guide

Game devs are now as numerous as struggling actors in L.A., says Cliff Harris, so prosperity is a matter of finding your niche and investing in marketing

Cliff Harris is not afraid of complexity. A year ago, during an "Indie Soapbox" session at GDC, he gave the most rabble-rousing talk in an hour specifically intended to rouse the rabble. The proliferation of affordable, streamlined engines like Unity, he said, had sapped the indie scene of the very thing that drew him to game development in the first place: as Harris put it, "the need to master the bits and the bytes."

Almost exactly 12 months later, and Harris is still very much a believer in the rewards (both personal and professional) of understanding how to grapple with and tame complexity. "It kind of annoys me that I'm not in VR," he says, making him what must be one of very few people visiting GDC in 2016 that isn't tinkering with a Vive, Rift or the growing army of alternatives. "Optimisation is back, and that's my pet topic. I love optimising code.

"This is how deranged I am: I was getting stressed, so for fun I went back and multi-threaded the loading for Democracy 3 to get it down from 1.2 seconds to 0.6 seconds. It's completely pointless, but when I'm demoing it and it launches I think, 'Fuck yeah, look at that!'"

"I don't think I'm the best in the world at making a complex political strategy game, but I am the only one. I kind of own that space"

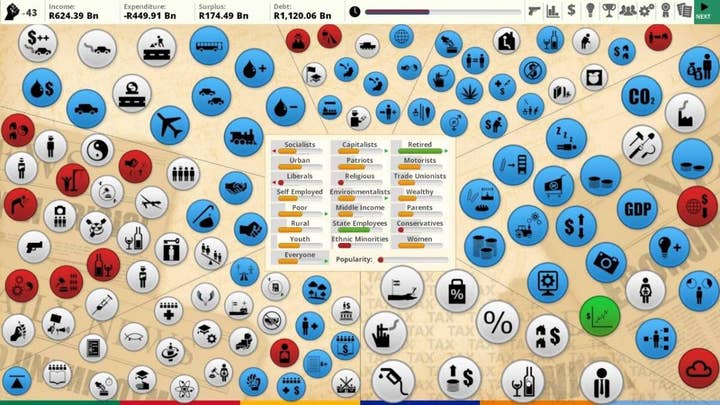

A trace of that spirit is evident in Harris' products, which he releases through the "one man company" he founded in 1997. Those looking for the latest pixel-art platformer will be disappointed; Positech Games specialises in detailed and, yes, complex simulations, the most recent example of which is an "expandalone" to the third game in the popular Democracy series, Democracy 3: Africa. Not content with modelling the intricacies of global politics and the vagaries of voter behaviour, Harris decided to tackle perhaps the most wildly diverse and - in certain countries - comprehensively broken region in the world.

Harris admits his distaste for the way people talk about "beating" games. In Democracy 3: Africa, the fascination comes not from winning, but from the myriad ways in which your strategies can collapse, and the degree to which cosier notions of right and wrong lose their lustre in the face of an imminent election.

"I was playtesting the game, and I thought, 'This is impossible. This is mad,'" he says. "And it's because we have all of these western liberal concerns. Like legal aid is one. Apparently, people in Egypt don't care about legal aid, because they've got other shit to worry about. We care more and more about the smaller issues the more we can just turn on a tap and get running water, or electricity."

Though the comparison is somewhat crude, my mind wanders to the GDC session from which I had recently emerged. Ostensibly an attempt to dismiss the notion of an "Indiepocalypse" occurring within the rapidly swelling developer community, the resulting discussion mainly served to highlight the comfortable circumstances offered by the nascent stages of digital platforms like Steam, iOS and Android. Finding players and generating revenue now require more guile and gumption than simply cranking a handle or flipping a switch. Where Tiger Style found a large audience for Spider: The Secret of Bryce Manor and Waking Mars with almost no promotion in 2009 and 2012, it underestimated just how much the market had changed for its Spider sequel last year.

"When I've gone wrong, I've misunderstood what people want, and kind of guessed what people want"

Almost every panellist had a tale of expected success giving way to unexpected failure, and their individual response strategies included a handful of common themes: more streamlining of gameplay, more friendly to streaming and YouTubers, an emphasis on multiplayer modes, and so on. It was difficult to escape the feeling that, now the well is running dry, everyone is pushing forward in a similar, easier-to-grasp direction.

"That's just suicide, I think," Harris says. "There's a really good book by Peter Thiel, Zero to One, where he says that competition kills everything, and really you want a monopoly. Monopolies are dumb, evil, but what I'm saying is you want to be the only game that does what you do. I don't think I'm the best in the world at making a complex political strategy game, but I am the only one. I kind of own that space.

"It seems small, and if I pitched [Democracy 3] to most indie developers as a reaction to the Indiepocalypse, they'd say it's ridiculous - 'Who's gonna play that?' But on Steam it sold 600,000 copies, and that's a big hit as far as I'm concerned. I didn't make it thinking it would be popular. It's the game I wanted to make, and I went full on to make it the kind of game I would enjoy. Nobody's tastes are that hip and niche and interesting that there aren't 50,000, 100,000 people who will see what you're trying to do.

"When I've gone wrong, I've misunderstood what people want, and kind of guessed what people want, and what I should have done is what you should always do: make exactly what you think is cool and be passionate about it."

Of course, this is just the kind of optimism that leads so many developers into trouble, but Harris returns to one argument that underpins his entire approach. "Market it," he says, bluntly. "Nobody markets anything. I reckon everyone who's goes to GDC to just sit in the audience who's worried about their game should have saved the airfare and spent it on marketing instead."

With so much product and relatively few storefronts, a marketing budget now has equal value to the idea on which it is spent. Something as commonplace as a pixel-art platformer needs a way to stand out from the abundant alternatives. Something as distinctive as Democracy needs to find its way to the attention of its intended niche. In both cases, the importance of marketing is huge and, in Harris' view, generally under-appreciated within the indie community.

"It's the point-of-view of people who go to a lot of shows and go to a lot of parties, so everyone hears about their game, right? They hang out with game developers, and that's their world," he says. "But there's a whole world out there that will only hear about your game if they read coverage of it, or see an ad. And obviously coverage is brilliant, but you can't time it, you can't curate it - so you don't know 'When?' or 'What?'

"There's a whole world out there that will only hear about your game if they read coverage of it, or see an ad"

"I actually like advertising as a business and an individual, because when I see an advert for, like, the new, amazing Call of Duty game, I think, 'Activision has paid money to put that in front of me and tell me their game is awesome, and obviously they'll say that.' I think that's honest, whereas if I read a big article about how awesome Call of Duty is... I prefer to see an ad, so I know where the money went, rather than, 'Did they fly that journalist to the Bahamas and show them Call of Duty?' I always worry about that. I'd rather know, 'This is sponsored, and this is not.'"

Anyone who follows Harris' blog will be familiar with this kind of forthright analysis, often unvarnished but always with the intention of providing clear-eyed insight at a time when certainties are in short supply. And his understanding of the indie market is more important than ever before, because Positech is now also a publisher. The decision to enter publishing was taken on the basis of finding commercial success with Positech's own products - "if all the games I'm publishing absolutely crash and don't sell a single copy, I don't have to sell my house" - and needing an excuse to take a break from the "lonely job" of solo programming to take the odd lunch with a fellow developer.

"It has been a good investment, but it's also risky," he says. "Each one is £100,000, probably, and my first house was £85,000 - y'know, back in the day. So I'm taking the price of a luxury sports car and betting it on someone I've met and their pitch. Unlike a lot of people, I don't want a vertical slice. I want to meet a person, talk about their game, let them show me what they think it might look like - they can draw it, if they like - and then go, 'Okay, let's do this.' That's a huge risk, but, to be honest, I like the business side of it. I like making that judgement call."

So far, those bets have paid off. Big Pharma, in particular, performed beyond his expectations, justifying his selection criteria of only working with games he'd play at home - and play a lot. Shadow Hand, an RPG card game, was chosen on the same basis, and Harris has similarly high hopes for its performance at market.

Whether those hopes can be interpreted as confidence, though, is another matter. In that GDC session, I watched a handful of developers perform feats of mental acrobatics to deny the existence of an Indiepocalypse while simultaneously describing the entirely unexpected failure of games that, four or five years ago, would almost certainly have turned a profit. Harris offers a single word in response to the idea that the Indiepocalypse isn't real - the word is "Bollocks," since you ask - but also a clarification.

"People haven't quite realised that you probably won't make it unless you're amazingly good, and hardworking, and whatever else"

That increasingly divisive phrase, Indiepocalypse, doesn't describe a single event in which all indie development will cease to exist. Rather, it is an umbrella term for a handful of very real factors and forces that are unsustainable in the long-term. A contraction is inevitable at some point, he says, and the indie games that do make money are not evidence to the contrary.

"There's literally too many game developers, in the same way that there are too many struggling actors in Los Angeles," he says. "What I think we need is for more people to be honest about that. Take a comedy character like Penny in The Big Bang Theory, who's a struggling actress so she's waitressing. Everyone understands that because they all understand that it's suicide trying to make it as an actor, because, 'Jesus, the competition.'

"We don't really have that with game development. People haven't quite realised that the reality is you probably won't make it unless you're amazingly good at it, and hardworking, and whatever else. What will happen is loads of people will burn through their savings and think, 'Well, that was just ridiculous,' and go and get perfectly good jobs in banks and engineering and finally accept that the games industry is too tough. And I think that's true."