Why Godus is probably 22Cans' last game

Molyneux: "We're going to be centralizing all of our creativity on one entity: Godus."

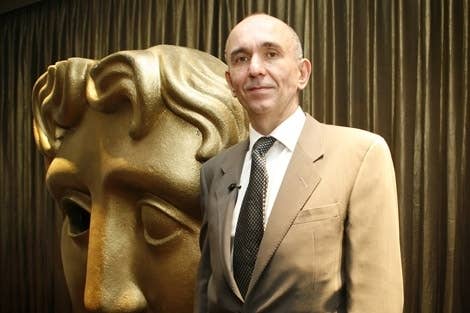

Sitting down on a sofa in Peter Molyneux's hotel room, we're presented by the most spectacular view. Up here on the 29th floor of the Intercontinental, San Francisco is laid out beneath us like a child's sun-drenched playset. Whole city blocks are reduced to low-poly squares shimmering in the heat haze and the hills beyond the city limits are flat textures - artificial boundaries for the sandbox we're spending the week in.

With the inventor of the god game genre perched next to me, I'm half-expecting a giant cursor to swoop in from one side of the vista and start plucking buildings from the ground, but California remains, inert yet bustling, as we look up from the screen of an iPad.

We've just watched the most recent trailer for 22 Cans' Godus, Molyneux's latest take on the genre he created with Populus in 1989. It's classic Molyneux stuff - a gently narrated weave of suggestion and grandiose promises which is at once enticing and seemingly impossible. Peter is a man who's aware of his reputation, so I rib him gently about the 'modesty' of the sales pitch. He takes it in his stride with a smile and launches a well-rehearsed patter.

"That's the incredible thing about the cloud and connecting - that you can support these incredible numbers. Really the dream and the passion Dan, is to create a game which firstly isn't going to just be over and done with in a ten hour play session, it is something which will exist and last. That's why the game Godus is all about sculpting, but it's about advancing your people. Advancing from a primitive age over to the modern era. It's about connecting people together.

"At the very start of the game, you don't feel like you're connected to anybody. When you realize over this hill, there's another god doing what you're doing and what's going to happen when you start to communicate. It's been an amazing experience to go from being at Microsoft, having this idea, leaving Microsoft, setting up 22Cans, doing the crazy experiment with Curiosity so that we could get the technology which would mean that I could do that video, and here we are about four weeks away from the limited launch of iOS and turning that connection to all those people. We've gone through Kickstarters and Steam Early Access - it's been an incredible journey up to this point."

That Curiosity was a tech-testing ground for Godus is not news, but it does make me wonder whether that pattern is due to be repeated - 22Cans was founded under the auspices of iterated experimentation, after all. Molyneux has said previously that 22Cans will only make one full game - is Godus that game, or another experiment?

"Founding a company, an entity, grounded by the thought that we aren't just going to go and fill up one idea after another idea. We're going to be centralizing all of our creativity on one entity, and that entity is Godus"

"I think part of the incredible place that we are in this industry now is that we could support a studio like 22Cans, which is just devoted to one thing and that is to making one game. Making a game in the same way, and this is a crazy, stupid analogy but it kind of sums it up, the product company that runs Coronation Street didn't immediately think when they released their first product Coronation Street what's the next thing they're going to do? The first thing that they thought was how are they going to structure a production company so Coronation Street can come up every single day of the week for the rest of time.

"But that's what they did. That inspires me more because I just imagine what an incredible thing it would be to take people who are playing Godus on this journey. This journey through time. This journey of evolving their people through what happens after you do connect all these people together. What happens? Will they all fight, will they all cooperate, will they be nice, will they be compassionate? That will be a fascinating thing.

"Founding a company, an entity, grounded by the thought that we aren't just going to go and fill up one idea after another idea. We're going to be centralizing all of our creativity on one entity, and that entity is Godus."

That entity epitomises one of Molyneux's career goals - a unified playspace which unites audiences and enables emergent interactions, building exponentially to a global community of self-governing societies.

"When you start out you're in this little home world and you feel you're not connected to anyone, and eventually after a few hours of play, your little followers set sail and then they travel to this hub world where there are other gods and their people in hub world. You can sculpt together and your little people can play. It's very very simple and then you evolve and then you earn the right to go up one more level and then it's my hub world, which I've called Guildford, vs. your hub world which you can call Farnham, competing against each other.

"To start off with, this home world is utterly and completely safe. You can let people into your home world, I can let you in to my home world. I can even give you permission to do things in my home world, but you have to go through several gates to do that. You have to make people absolutely sure, it is not on by default. It's like my own country there, it's safe, it's un-conquerable.

"My dream is to have an experience where casual gamers and pro gamers can play together"

"The community that we've created, that is something which can be - I think the word invaded is wrong because you can be competed against and then at higher levels, we're talking about one community, not like Guildford and Farnham anymore, it's like Surrey and Sussex, counties rather than towns. They're going to compete and then eventually they'll be countries like England and Scotland. They may well go to war, but that's way up here."

For a game so centred on interaction, Godus has little in the way of direct communication - in fact, there's no chat at all. For Molyneux, this is a way of building community, rather than limiting it.

"My dream is to have an experience where casual gamers and pro gamers can play together. The very fact that a casual gamer who may have only played Candy Crush Saga or something like Hay Day before then meets a Call of Duty player, well how are they going to feel? They're going to feel intimidated.

"If I remove that problem by removing the chat and only allow communication through the game, then that becomes more interesting because the assumptions that you make about a person isn't by what they say in text, it's about what they do in the world. It's communication and what we found in Curiosity is that people found it incredibly bizarre what it is to communicate. Not very interesting, because we only designed Curiosity. We intentionally didn't make it easy for people to work out where they were on the cube.

"Wherever you rotated the cube, it looked like everything else, but people still worked out a way of saying, 'I'll meet you here'. They did that by putting little signs. I think at the moment, with casual gamers that have only played a few games, they're like kids in a school playground on the first day.

"What do those kids do? They try and find a corner and they to become invisible. You've got to allow them to be invisible. When they gain confidence, when it's the second day or the second week in the school playground, they'll come out of their shell and they'll feel confident. You give them that confidence by making them feel proud of what they've done. By making them feel useful. That's why it's such a simple mechanic about this. Anybody can do it, you feel useful straight away."

If Godus is to be the game which 22Cans works on for as long as the studio exists, and if it could potentially be the final game of Molyneux's career, it has to be right. Molyneux has always been a man of great vision, but more than once that vision has had to be tempered by the reality of publisher deadlines, financial restrictions or technical realities. This time he's opened the development process up to the harshest of investors: the general public.

"It's insanely risky," he says, reflectively. "It was a wonderful moment when everybody said they played the early access and that the game was boring. You can learn from that mistake. There were two reasons why it was boring. One, there was way too much clicking and also they only had a quarter of the entire experience. They didn't have the hub world stuff, they didn't have any event stuff. It's still an incredibly instructional thing.

"I am no longer a designer that has ideas, I'm a designer that has ideas and curates other ideas. Those ideas are groomed from data, like analytics, they're groomed from community boards, and they're groomed from the social space. The accumulation of that goes into ideas for the game."

The negative feedback for Godus has been, as you might expect, a little unbridled. As much as that might have been something he was prepared for, it must still be a fairly brutal thing for Molyneux to endure - how frustrating was it to be judged so completely on a pre-alpha, even after such an iconic career?

"That's the world we live in, man," he laughs, philosophically. "If Spiderman 3 comes out and we see a trailer, we make a judgement on that trailer. It's just 90 seconds and of course we shouldn't, but that's the world we live in now. It doesn't mean that you shouldn't reveal yourself. The end always justifies the means. We have to have people play this game. If we closed the shutters and just developed it blind and then released it, I think we would've failed, but the very fact that this game has already been played by over a million people - we've looked at the data from over a million people.

"That makes the chances of success far far higher and that's worth the risk. I don't mind if people turn around and say, 'You know what, that early access was boring. There's too much tapping and clicking.' It would be a sin for me not to respond to that."

It's certainly proven successful for some other notable titles, we discuss Day-Z and Rust for a while and I mention the fact that Facepunch's Garry Numann actually told people not to buy the alpha, and ended up getting 250,000 downloads in a fortnight. Molyneux nods.

"The first thing it says on our Steam Early Access is don't download this if you're expecting a huge game. This started off at 29 per cent, it's now only 49 per cent of the entire experience. It says underneath, do not buy this if you're expecting the final game. No one reads that, of course. They just download it and play it. I think Garry is right in saying you have to warn people. I think Steam Early Access is incredible because really what you're buying is you're not buying finished game, you're buying a season pass for the entire game and what it will become.

"If I really want people to play this for months and months and months, I cannot smack them in the face with monetization and demand through their addiction of the game that they pay me money"

"The first time I saw that really work well was by Notch on Minecraft. He said, 'This is a broken experience, but you're buying a season pass forever.' The saying is true. It is unique, it is, although I do think monetisation itself is about to go through a huge shake up. What we think of a 'monetisationer' is going to change a lot.

"This is where I have to be careful," he says, when I mention free to play. "On iOS it is free to download, it's absolutely free, you download it. Then once you experience what we do, it would be wrong for me...If I start saying free to play, that's going to make people think, 'Oh my god,' and there's so much hatred about free to play. So I have to invent a new term, that's the only way I can describe it. What we're trying to do is we're going to try and create something called invest to play. "All we're going to do is tempt you to spend money. It's just a temptation. My inspiration, and this is insane, is a supermarket. I walk into the super, I'm going for potatoes or I'm going for a sandwich, but invariably more through the supermarket I walk in the fresh fruit counter, I think I'll have an apple. I walk past the fresh bakery section, have a loaf of bread, and before I know it I come out and my arms are laden with stuff. I don't feel like the supermarket has beaten me over the head and demanded that I shove my shopping trolley full of stuff. They've tempted me.

"If I really want people to play this for months and months and months, I cannot smack them in the face with monetization and demand through their addiction of the game that they pay me money. The industry is just a bit insane because what a lot of companies are saying is, 'We make all of our money off less than five per cent of our users,' and quite clearly those 5 per cent of the users are hooked and addicted and quite a lot of those are kids.

"What's going to happen, Dan, is the government's going to turn around - the Korean government are doing it, the British government are doing it - they're going to turn around and say, 'We need to do something about this.' There are kids out there spending hundreds of pounds of their parent's money. That is very short-term. That relationship, that digital, financial relationship we have with consumers is changing. It's changing for all forms of media.

"It's changing for music, and for films, and for computer games. We've just got to embrace that and make sure that people want the best. They want to pay money. If you can get people to want to pay money just like people want to spend money on a hobby, then that's great.

"I want to turn it on it's head and say, 'Right. I want 95 per cent of the people who play Godus want to pay money.' Want to pay money because they're enjoying it so much. Rather than 5 per cent wanting to pay money."

That moves me on to something I'd been subconsciously avoiding: Dungeon Keeper. I mention it, tensing slightly, but Molyneux's been asked every awkward question a thousand times and he seems to have been working on his diplomacy.

"What was so frustrating about Dungeon Keeper was that underneath was a really good game which was faithful to the original Dungeon Keeper. It would be so easy to correct that, but you look at the top grossing charts, Dungeon Keeper's in there. They're not going to turn around and say, 'Actually, guys, we're just being really lovely about this. We'll stop making money.'"

It's a fair point, and the disconnect between what gamers and critics see as gouging and what free-to-play customers are willing to pay has perhaps never been clearer. I ask Molyneux how he thinks it all came to be.

"It's the analytics people. I've had analytics people in talking about Godus and they come in and they say, 'This is how it's done. If you do it this way, you'll make X amount of money, if you do this way you'll make Y amount of money. Do it the X way, no question about it.' It feels like analytics just believe that they have the answer and it's the only answer.

"It gets harder and harder to squeeze money out of addiction. That's what drug trafficking does"

"You've got to introduce the concept of gems within fifteen seconds of people buying an app, you've got to get people spending gems within the first two minutes. There are these rules, which when you see them written down, you look at a lot of games on the app store, you realize that all these rules are the same. They're harsh and they're brutal and they're all about that five per cent of whales.

"What that is doing is creating consumers that, when they pick up a new app, the first thing they say is, 'I'm not spending money on this. No matter what it is, I'm not spending money.' It's just very short term. You lose them forever. We've got this brilliant opportunity to do the thing we've been saying we've done for years. It's been years now that we've been saying we're bigger than the movie industry, the music industry, that's a load of bullshit. We're not. We make more money than them, but we don't have anywhere near the number of consumers. Well now, we have these little green shoots of new gamers and if we don't treat them right, they're going to just go away. It's an opportunity to have billions of people playing games. So where they consume music is the same way they can consume digital entertainment and that is a fantastic opportunity.

"I think even Apple knows that. I wouldn't be surprised if they're just legislated against. It gets harder and harder to squeeze money out of addiction. That's what drug trafficking does."

He sighs, looking a little deflated and surprised by his own burst of exuberance, but then his quick smile returns and my time on the sofa in front of that incredible view is over.

"There we go, that's my rant for today," says Molyneux as we shake hands. "A grumpy old Englishman with jet lag, ranting about everything."