Bithell: "You stop looking punk if you used to be in Boyzone"

On Twitch, Thomas and why today's indies are tomorrow's corporate execs

"No-one had heard of it for the first six months. For the first six months it was a failure, a flop. Everyone ignored it."

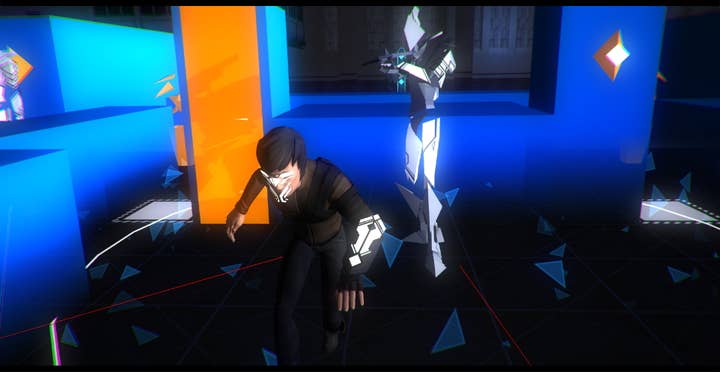

It's easy to relate now, with the breezy grin and warm tone he's become known for, but it's probably fair to say that Mike Bithell might not have been telling this story with the same casual enjoyment had Thomas Was Alone remained in a state of 'failure'. As it was, he's done rather well out of it, making a genial move from a job at Bossa Studios to fully-fledged independent with a second game, Volume, well on its way. He's also in absolutely no doubt as to what fired Thomas into the public consciousness, and it wasn't the press, YouTube or PR.

"It was Steam," he tells me with certainty. "That was the big one. The game came out in July of 2012, it went on Desura and I was selling it direct. It made a bit of money, enough for a small holiday. Pocket money, basically. I was working at Bossa at the time, so it was fine - I'd made a game, it hadn't sold brilliantly. I'd try again in a couple of years when I'd got the enthusiasm to do it again.

"But I kept emailing Steam - this was back when the only way to get on there was to just keep hassling them. Mates who had games on Steam had been putting in good words for me, but I was struggling. Then they announced Greenlight, for October. They did it at this big, swanky event - they had simultaneous events in the US, the UK and a few other countries as well. They gathered all the indies in an area - basically the mouthiest ones from the internet - and put them in a room to explain what Greenlight was. I guess it was to allay any fears. I managed to get myself into that - again via a friend. No-one had heard of me, I wasn't an indie who was cared about.

"When they actually announced Greenlight, I just sat there, terrified. I just thought I was going to get lost in all the noise"

"When they actually announced Greenlight, I just sat there, terrified. I just thought I was going to get lost in all the noise. I went to speak to the Valve representative at the end and said 'Hi, I'm Mike.' She said 'Oh, you're Mike Bithell, you made Thomas Was Alone.' I was amazed. She said 'We should get that on Steam, maybe in a month or so?' I agreed."

He's underplaying it a bit, I suspect, but he does seem genuinely surprised by his success.

"We launched in November. I remember watching the counter go up via Steam analytics. My goal then was to get a year's salary - if I got that, then I was going to quit my day job. I got to a year's salary at midnight on New Year's Eve - I stayed home to watch the counter. Then the next week there was the Total Biscuit video and by the end of that I had two year's salary in the bank. The next week I had three. We were already working on a Sony port because Shahid loved Thomas - to be fair, he liked it before anyone else did, he's such a hipster, bless him."

The discussion turns to Greenlight as a system, what problems it's solved, and what issues it's caused. It's interesting to hear that, even whilst it was being announced, developers were already concerned about the flood gates opening. Was the program ever intended to solve any curation issues, I ask?

"I don't think it's an answer to any curation problems," muses Bithell, "but I don't think it's an attempt to answer the curation problems, either. Valve is a very small company, intentionally. The problem they have is that they've become a dominant platform - everyone wants to go on Steam. I think that's the problem they were trying to solve: 'how do we deal with the influx of games without employing 20 people to just answer emails?' Because it's Valve, they built a software solution.

"I think what happened then is that they've opened the doors and everyone has jumped in, which I think is a good thing, but now games become invisible because there's so much content. I don't think it's solved the curation problem, I think it's created it. Knowing Valve, a solution is in the works. I think they'll do exactly what Gabe said in that interview a while ago - every user on Steam will have a curated storefront where they'll put everything they like. Gabe will have his own, which will become the de-facto storefront as was, YouTubers will have theirs.

"I think that'll be really interesting because then you'll be speaking to those people in order to get visibility. What we lose, and what I think scares a lot of the established indies, is that one button, that big button that everyone saw, that had your game on it. It was massive, unprecedented - it meant you didn't have to do any marketing. A whole generation of indies, myself included, gone really big purely because Valve chose to put us on that front page. I think if that's how you made your millions then you're inevitably going to look at that being changed with a degree of fear. That's scary, because you were relying on it to make more millions with your next game, plus, you've got a mortgage now. On your fourth home, in some cases."

With the app store's burnish diminished somewhat for indies hoping for big exposure, it's easy to understand why developers are expressing similar concerns over Steam. Arbitrary as it may be, someone has to draw a quality line somewhere. Bithell is confident that Valve has something in the works, but he's also enjoying the disruption.

"If you're established then you're thinking 'oh no, all this riff-raff is coming in and stealing my visibility.' I think that both sides of that debate are being a bit selfish and I think that's OK. That's business, right?"

"All indies like to be awesome and nice to each other," he laughs, "but I think that all the parties in the conversation have their own selfishness: 'what can make my game successful?' I think if you're someone who's not established, you see this as awesome because you're now going to be on Steam and, if you're lucky, that can lead to loads more sales. If you're established then you're thinking 'oh no, all this riff-raff is coming in and stealing my visibility.' I think that both sides of that debate are being a bit selfish, and I think that's OK. That's business, right? I want to make games in perpetuity and in order to do that I need to sell them. I think it's a very interesting debate to watch.

"I suspect that we're looking at a half-finished solution at the minute, but I think it's going to get solved. What I do think though is that you can't go backwards - I think we're coming into a situation where marketing is going to become much more important again. There was a magical period where you could make a game, someone at Valve would think it was OK and you'd sell millions of copies. That time has gone. I think it's going back to old-school marketing, PR endorsement, YouTube, the press."

That brings us around the a discussion of the cyclical nature of a lot of developer's careers - that slash-and-burn farming process which begins with a diaspora of talent when a large studio goes under, flourishing into a number of promising start-ups, then winding up with those on top becoming the proverbial mahoganies of the jungle, replacing the behemoths which spawned them. We talk for a while about Boss Alien, which was formed by staff from Black Rock after Disney shut it down in 2011 and was acquired by Natural Motion in 2012. When Natural Motion itself was bought by Zynga in January this year, the cycle was complete.

As a man with a history at both Blitz Games and Bossa studios before his going it alone, Bithell knows how that process works, and doesn't see it changing.

"History up to this point has shown it to be reliably repetitive, so I don't think that will change. You never know for sure, but... A lot of us indies think we invented this stuff, but if you look back at the Darling brothers, the Oliver twins, David Braben, that generation - they were all doing essentially the same thing. They made their money, started their companies and built them up and now you hate them," he laughs.

"Even Activision was a bunch of devs who wanted to take credit for their own games and put their names on their work. They were indies, they had that attitude. Now they're the evil empire, as far as some people are concerned. We're all in the same thing.

"This is why I'm trying to move away from using the word indie as much, because we're all devs. I don't like the rhetoric which gets thrown around, in both camps. You talk to AAAs and they think indies are all hipsters who don't know how to make a good game, you talk to indies and they think AAAs are evil, soulless people working overtime every night and hating their lives. Usually they've never met.

"I'm in a nice position, because I used to work in that space, to be honest most of the successful indies did. We all work very hard not to say that, because you stop looking punk if you used to be in Boyzone. There's a mythology about it. It's something I'm talking at Develop about, actually - that we need to stop creating these myths about the bedroom coders who made it big. They weren't bedroom coders, they were people like me having a job in the industry already. In order for Thomas Was Alone to exist, I had to work for the Oliver twins for three years to learn how to make a proper video game. It's an interesting cycle.

"The moment I'll know I've genuinely achieved something is when I read a blog post by a 20 year old talking about my evil company and how it needs breaking down."

"This is why I'm trying to move away from using the word indie as much, because we're all devs. I don't like the rhetoric which gets thrown around, in both camps"

Being identified as an establishment target might be a bitter-sweet gratification, but Bithell has had to take a slightly different road to that trodden by the alumni he's been mentioning. I joke about his Twitter presence, but for Mike, new media forms have been a huge factor in success: Twitch, YouTube and social media are all essentials skills in the modern indie toolkit. I confess to him that I fear the online press has spent too much time gloating over the demise of print to pay proper attention to the shadows of new forms of games coverage sneaking up behind us - although sneaking is a dubious term for the likes of YouTube and Twitch, both of which have arrived with plenty of fanfare.

"I think the biggest lesson that people have learned is that it's all about accountability, transparency and honesty," he says when I ask him how much these new media have affected his PR process. "There are deals that are done - people pay for YouTube videos, I don't think that's any secret. That's not how I choose to do things because, frankly, it would backfire on me. I'm too visible, too known. I can't do stupid things - if I'm a dickhead to someone on the internet, that's going to haunt me, because I've tied myself so closely to my business, my work. It's accountability. And being likeable. That's what I saw with Phil Fish - his problem was that he got angry, that was very hard for him. I was watching that, because it was around the time that I was coming up, and I realised that I have to pretend to be friendly, even when I'm angry. It's about being friendly, cool and nice.

"What's interesting now is that I'm making games with other people, my immediate instinct is 'am I being a dick for taking credit for their work?' Framing myself as an auteur while other people are swept aside. I discussed it with Daz, my right-hand man on Volume. I asked if he wanted to switch to trading under a company name, rather than mine. He told me that my name would make him more money," he says with a smile.

"The video stuff, though - I think it helps that I'm quite young, that I'm in the same age-bracket as those people making the content. Interactions don't feel like false relations, I don't feel like a 50 year old businessman. I know that's going to happen, though. I'm very aware that they're going to become the establishment and I'm going to lose that relevance. Hopefully by then I'll be known for making good games instead."

Thomas Was Alone exceeded all of Mike's expectations, and put a decent warchest behind his lofty ambitions, but he's well aware that not every concept has that run away success. He's prepared for lean times as well as the bountiful harvests, and that means not over-committing.

"I know at some point I'm going to flop. There's going to be shit games. There's no creative in history which has made hit after hit, getting better and more successful each time, that's never happened"

"Yeah, it's terrifying," he says, frankly, after I ask how scary it is to hire people, to have that responsibility. "Right now it's me and about nine freelancers who are basically all people who I've worked with during my career, people I know and trust. People from Blitz, Bossa etc. Employing people is scary because it means HR and tax brackets. I mean, I pay taxes now, but I have someone who handles it and I'm not really aware of it. I just know I have to keep giving the government money, which is great. Schools are awesome!

"It's weird to think of scaling up, though, even though I think it's going to happen. The rule that I set myself after Thomas was...well. Thomas cost me a lot of my time, which I wouldn't put a price on, but in terms of cold, hard cash, about £2000-£4000. I scrambled that money together via various means. With Volume the plan is that each game from now pays for two more games. At the point where I started Volume, it looked like Thomas was going to make about twice as much as I needed to make Volume - it's actually turned out to be enough for about three or four, which is nice.

"Inevitably, though, I know at some point I'm going to flop. There's going to be shit games. There's no creative in history which has made hit after hit, getting better and more successful each time, that's never happened. So my logic is that as long as I make twice as much at least half of the time, I can keep doing this in perpetuity. If I make better games or have a hit rate above 50 per cent, then my output can go up. In retrospect I think that Volume could have been done for a similar price by a team of five people in an office. As it is I've paid a lot of money in freelance. I think Volume will probably be about $250,000 by the time it's done. That's fine because it's a $20 game, so I only need to sell about 20,000 to make even, that's very doable.

"At my scale that's a very good business case. If I keep making games for under $1m, I can recoup it pretty reliably. Unless I start making crap games. I'm taking my time, I've seen too many idiots buy sports cars."