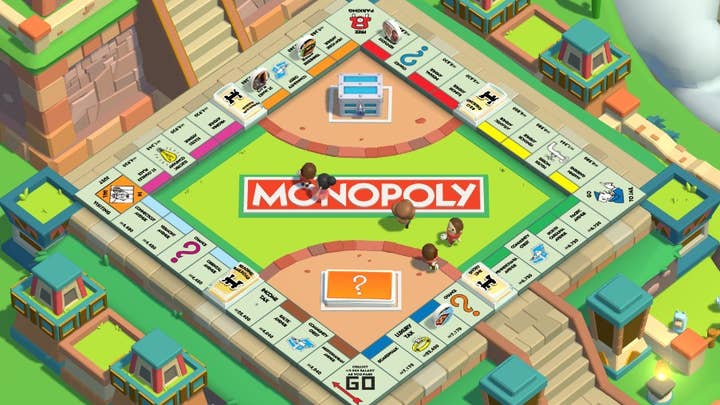

Making the most of Monopoly Go's false start

Scopely's Massimo Maietti talks about the abandoned original version of the game and how going back to the drawing board produced a breakout mobile hit

Monopoly Go has been an instant success for Scopely. The game launched in April, and topped the US mobile charts in August. And this is during a time when the mobile market has been so hostile that mobile publisher Playtika has given up on new releases for the moment because it believes they just aren't economically viable.

In speaking with Scopely's GM of Monopoly Go and VP of product Massimo Maietti, the game's success in the face of a challenging market is the first thing we ask about. Maietti acknowledges the market dynamics have been unfavorable for many, but says Monopoly Go was well-suited to the landscape it launched into.

"I think very few brands in the world have audiences that come into the game experience expecting, wanting, and having a predisposition to play with their friends and families," Maietti says. "We thought if we could harness that built-in interest with a game that would be truly social so you would feel OK inviting your friends and family because the game is for everybody, the game has a chance to really scale.

"That was one of the reasons we were very much interested in Monopoly as a brand from the beginning. We felt it still had yet to find its most mature interpretation on these platforms."

That most mature interpretation has proven elusive, even to the team behind Monopoly Go.

In fact, the Monopoly Go tearing up the charts these days is not the original. Maietti and the team actually started work on a very different Monopoly Go.

"It was a synchronous PvP game that required a lot of skill, a lot of commitment, but also as part of that genre was really hard to play with your friends because you might not be online at the same time and things like that," Maietti explains.

The results from testing that version of Monopoly Go suggested that it might be able to sustain a reasonable business, but it wasn't shaping up to be a big hit. One of the reasons for that, the team concluded, was that the gameplay didn't quite fit the brand.

"You became rich by taking these actions in a real-time, frenetic game situation," Maietti explains, "so it felt a lot like labor. You got rich by laboring through your game and you end up with more money than your opponents, win the match and move forward.

"It felt a lot like labor... But then we realized that the fantasy of Monopoly was actually that you get richer by having money"

"But then we realized that the fantasy of Monopoly was actually that you get richer by having money. You just have lots of capital and these hotels, and then capital multiplies because people pop up in your hotels and you get richer through that."

And in very Monopoly-appropriate fashion, the team dismissed the idea of a reasonable business because it wanted more.

"We had this insight that we made the wrong game on a fundamental level," Maietti says. "The game we built might have been fun enough in itself, but it was the wrong Monopoly game… We thought, 'If we can have a meaningful business with the wrong game, imagine what it would be with the right game.'"

They went back to the drawing board and re-envisioned Monopoly Go as an asynchronous event, but kept a focus on the game's social/viral hooks, like its invite system to introduce new players to the game through their friends. In some ways it's reminiscent of the Facebook titles of a dozen years or so years ago – titles Maietti knows well given his prior experience at Zynga during that era – but he emphasizes Monopoly Go is using a very different and more targeted version of the idea.

"The game definitely does not incentivize you indiscriminately inviting all your contacts," Maietti says, "It's a small group affair and we try all we can to have you play with the meaningful people in your life. After six or seven or those, there's no benefit to you to have more people."

He says it's a user acquisition strategy that can be very successful for the right game, particularly one with mass appeal to virtually every aspect of it, including the look, feel, skill level, visual complexity, and art style, among other traits.

"For you to feel comfortable inviting them, you need to play an experience that you feel anybody could like," Maietti says.

Second, Maietti says the game has to be aiming for a large daily active user base. If it's not going to have that, social systems like clans that group people together by playstyle or preference may be better to create a socially active game even with a comparatively smaller player base.

"You need to have the resources to push for a large DAU because the chances you have somebody in your life that plays the game need to be high to create this network," Maietti says. "If you only have individual users here and there, it might be very hard to create this large a network. Working with Monopoly gave us the confidence that at least there was the potential for these things."

Maietti calls it a "high-risk, high-reward" approach, and one that changed the way the company tested the game in soft launch.

Where the team would normally look at individual KPIs and focus on metrics and play patterns from individual players, for Monopoly Go's soft launch markets, it was more about testing whether or not the social elements were working.

As Maietti explains, "That led us to not only take a bite of the market and see how it is, but we entered with the notion, 'Can we win in the market? Can we be top-grossing, or top five grossing, or top download for weeks at a time in that market? It was really about whether we could create a network of users that is healthy enough to just take over the market."

That's pretty much what happened. Maietti says it's "extremely rare" for a game to take hold of a market during its soft launch phase like that, and something he hasn't seen since back towards the height of Facebook games.

"From the very beginning we saw a great interest people had in connecting to Facebook or the contact book on their phone to connect with friends and family," Maietti says. "We clearly saw the social network created by the game expanding, and all the players who were inviting each other and having incredible retention and other KPIs. That gave us a lot of confidence."

"We didn't try to test the water, have the core loop and some embellishment and see what it did. We really went all in"

Maietti points to another key difference with Monopoly Go's soft launch. Instead of using the launch to tweak and test and zero in on what the full game experience should be, Maietti says Monopoly Go soft-launched as a nearly complete experience.

"We didn't try to test the water, have the core loop and some embellishment and see what it did," he says. "We really went all in. We validated what we were doing through plenty of internal playtesting, lots of external users being invited to play the game. We tried to be humble and to check and understand in every corner what we were doing, but the results from the test gave us some confidence that we could keep the bar high and we could give ourselves the sterner test and still pass."

The results speak for themselves so far, but there's a big difference between an initial success and an evergreen chart-topper in mobile. The industry has always had its fast starters that run out of steam, and while strategies to maintain momentum have evolved over the years, Maietti says it's still something lots of developers struggle with.

"I personally do not think this has become a science," he says. "You can see the shape of the curve and some games shoot high and disappear just as quickly. Some games grow slowly over a long period of time and so on and so forth. I think the problem the last year has certainly become more multi-dimensional. It's no longer the case that you win by having a really great game design. That's needed, but you also need a great structure around data and insights from data. That's now needed, but it's also not enough. You need a deeper integration between what the game does and what the marketing does.

"We had a few years where it might have felt like marketing could do whatever and it might benefit the game in any sort of disconnected way, but I think moving forward there needs to be much greater synchronization, coordination, and integration between those two.

"We had a few years where it might have felt like marketing could do whatever and it might benefit the game in any sort of disconnected way"

"I think there needs to be greater attention to communities, to make sure your communities are large and that what players tell each other is healthy and interesting, and the game team is embedded in the community and pleases the community constantly."

Those extra considerations make it harder to maintain momentum these days, Maietti believes, but he says as a part of Scopely, there are other successful games the Monopoly Go team can pull learnings from, like Stumble Guys, Star Trek Fleet Command, or Yahtzee With Buddies.

"We have a DNA of very diverse games that have mastered one or even many of those dimensions, and for Monopoly we've tried to learn within our ecosystem and bring it all together," he says. "We're still very early in the journey but our intent is to grow the game and make it an evergreen game."

While our discussion with Maietti began with a glum acknowledgement of the state of mobile these days, the developer is keen to end it on a brighter note.

"I want to communicate to fellow game makers out there that might have been struggling that there is hope," he says. "When we started… we weren't sure about where this journey would have ended.

"Through the application of this discipline and trust in the game making process, we got there and delivered a game that to the surprise of many has been so successful out of the gate almost immediately after global launch, which is something that seems almost impossible. But this story is that it's still possible to do it, and mobile can still be a vibrant place for large audiences to come together and have a great time."