Making Blaseball, at our mercy

The Game Band discusses making a community game led by its fans, and their adaptation to Blaseball's grand slam of popularity

Earlier in 2020, faced with worries of future financial instability and pitches being rejected, The Game Band creative director Sam Rosenthal asked one of his mentors for advice, and was told to "just make a game."

"Like, to not always be chasing money so that you can rely on your team to make something that you think they could make really well in a short amount of time," he explains to me.

The Game Band wanted to push boundaries with its next title, which it was trying to dream up following its Apple Arcade release Where Cards Fall. While the team worked on a few other, higher-priority ideas, Rosenthal opted to take his mentor's advice and put together a side project the studio could make and release quickly.

"We knew we would be able to represent it without any visuals. All we would need is the diamond"

Sam Rosenthal

He ended up inspired by his Zoom calls with non-gaming friends, who he says mainly wanted to play "not particularly well-made browser games that were just adaptations of board games or card games." Their enthusiasm got him thinking about people working from home, who likely had browser tabs open with things that weren't work. Rosenthal was also enticed by the idea of bringing a community together around a single idea, especially in the current socially distanced culture of a pandemic.

After an initially lukewarm reception from the rest of the team to his pitch of horse racing and a brief "snail racing" iteration of that same idea, Rosenthal and his fellow team members including Stephen Bell and Joel Clark landed on baseball. Or, as it would eventually become, Blaseball.

"From a scoping standpoint, we knew we would be able to represent it without any visuals," Rosenthal says. "We knew all we would need is the diamond because that's the experience of checking baseball scores on your phone. And that's how it's always been represented."

"A big rallying point for everyone is...they're all seeing the same thing," Clark adds later. "Even with an MMO or something, there are all the different servers and you're like, 'Which one should I join to play with you?' No, we're all looking at the same thing and experiencing the same thing together."

Rosenthal expected his game idea to take a week. It ended up taking three months, but he tells me it still didn't represent an enormous financial risk for the studio -- in fact, the game remained a side project for the studio up until the final two weeks of its development.

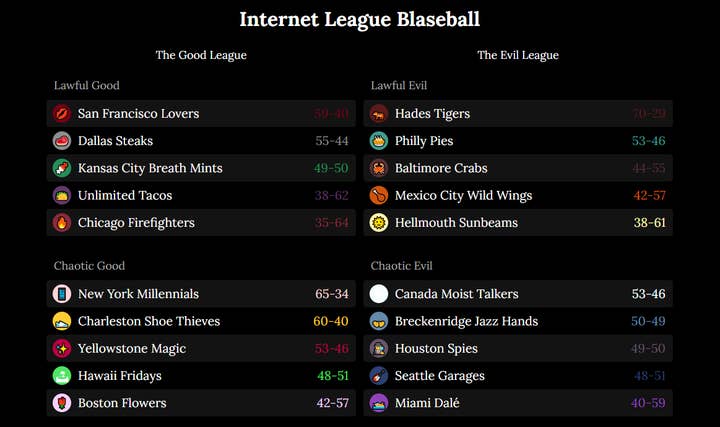

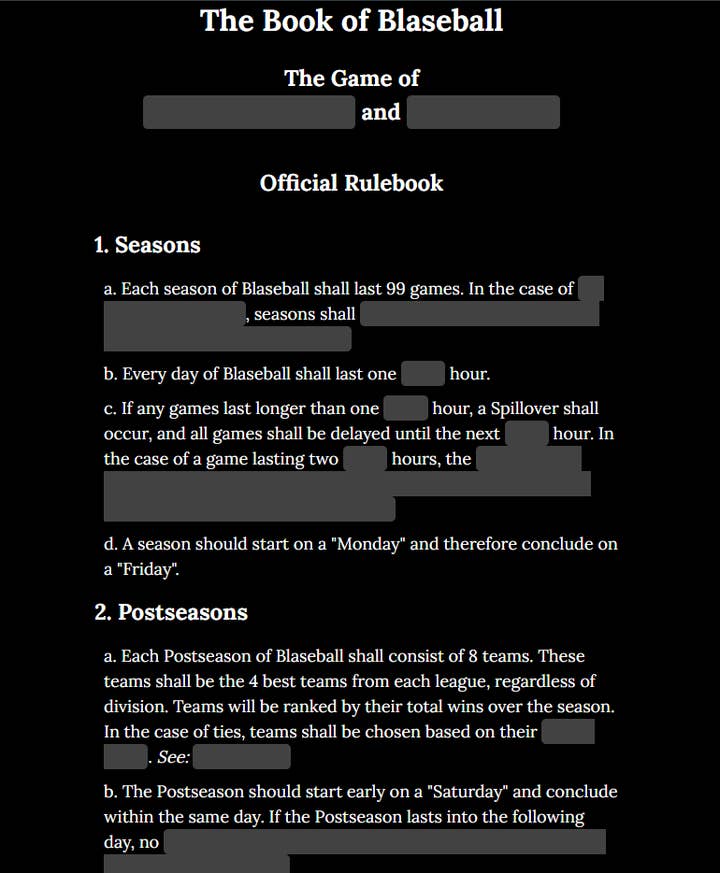

Thus, in late July, The Game Band released the quirky sports betting simulator known as Blaseball. The game features a fictional league of 20 teams (with names such as the Seattle Garages, the New York Millennials, and the Canada Moist Talkers) that play one another in simulated games across a 99-game season each week. The four top teams go on to a post-season on Saturday, everyone takes a break on Sunday, and the next season starts back up again on Monday.

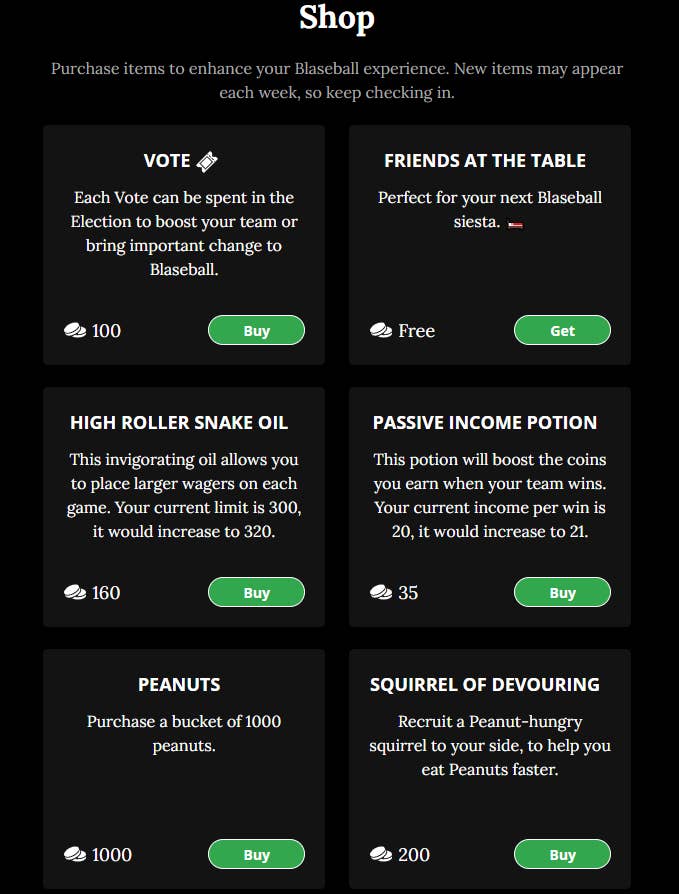

Players interact with the simulation by betting an in-game currency on the outcome of the matches, and then spending their winnings to "vote" for additional, often-bizarre rules and buffs for their teams to take effect in the following season. For example, one season's votes gave the four worst teams in the league an additional "fourth strike" before their players were out, while another vote implemented the ability for fans to buy and consume peanuts, the effects of which still aren't fully known.

"A big rallying point for everyone is...they're all seeing the same thing. Even with an MMO or something, there are all the different servers"

Joel Clark

Votes can also cause changes like players swapping teams, rerolling stats, or equipping themselves with literal Arm Cannons to improve their pitching. And the whole game is colored with a Lovecraftian aura where the fictional players -- with names like Jessica Telephone, Blood Hamburger, and Boyfriend Monreal -- might get incinerated randomly at the end of games, solar eclipses overshadow half the games being played at a time, and the fans' vote to open a Forbidden Book that launched the game into something called The Discipline Era -- for which someone presumably must atone.

Though that may sound wildly off the rails, the interaction of the audience with Blaseball on a fundamental level is very simple: it's just betting on the outcomes of simulated baseball games. While the game's bizarre lore and world-building are given a framework by the developers, much of that activity actually takes place in the official Blaseball community Discord and within the fan community, who build narratives, draw fanart, and speculate around the simple stories played out in each game.

Rosenthal compares their work on Blaseball to running a Dungeons & Dragons campaign.

"We're not really game designers in the traditional sense, where we're setting up like a very narrow space for people to engage with," he says. "We're giving them different stories. We have landmarks that are different, like little bits or pieces to riff off of, and we have an idea for different places where it could go and where we'd like it to go. But if the community pushes it in a different direction, then we respond to that. And we, in an ideal world, have enough things planned to respond very well.

"For the first three seasons, we were responding so quickly, and I think we did a decent job and the community was fortunately very receptive to all of the things that we were doing when unexpected things happened."

Though Blaseball can certainly be enjoyed without ever stepping foot into a Discord community, the fan congregations in the game's official server are a game component unto themselves. So much so that the developers necessarily need to keep a close eye on the community so intrinsically tied to their game, and have appointed the community managers currently in charge of it.

The server has some fairly strict rules that have been in place from the beginning -- it has a tight swear filter that doesn't allow for anything remotely resembling bad language, and the team has been proactive about banning trolls, as well as normalizing more welcoming practices like putting pronouns in usernames.

"For starters, that's important to us," Clark tells me. "There's no room for transphobia in that community. You can't allow any of it. If you warn somebody and say, 'Well, your transphobia was bad, just tone it down next time.' That doesn't work.

"We want to make sure that Blaseball is for everyone and that people are protected in it. And yeah, there's just no room for any sort of hate in that"

Joel Clark

"We want to make sure that Blaseball is for everyone and that people are protected in it. And yeah, there's just no room for any sort of hate in that. It's just such a loving community and we want to encourage that in every way."

Even though Blaseball has so far only run for three seasons, or three weeks, it's already exploded in popularity. The Game Band funded Blaseball initially via sponsorships for each season -- Yes Please Coffee for the first two, Friends at the Table for the third -- and once the studio saw the game's audience growing, it launched a Patreon as well that at the time of this writing is pulling in $4,500 a month.

That funding is about to be put to good use, as Rosenthal says the team didn't expect the game to be so successful so quickly. While the team is delighted by the response, they now are working to figure out how they can turn what was originally intended as a goofy side project into a more sustainable thing for them to run long-term.

"We felt like [Blaseball] would have the greatest chance for success if it was on the most accessible platform," he continues. "If there's any barrier in front of it, even if the barrier is like, download an app, that's still probably too much friction to find out if this weird thing is for you. But if it's just like, go on to this website and log in and find out, then that's probably enough.

"But since we're not web developers, we didn't really make it for scale, or to be able to handle a decent amount of traffic. So every time we got a spike in traffic, the site would collapse. And it was quite stressful because the only thing that we really knew how to do to fix the problem was to upgrade our servers. And as we started to do that, and I started to look at the bill coming in for that, I panicked a little bit and that was why we had to try to find a way to manage that."

What Rosenthal describes came to a head in Season 3, when several people attempted to exploit the game's new "Peanuts" mechanic, resulting in a level of activity the website couldn't handle. The season saw the website go down several times, and finally, the developers called for a two-week hiatus so they could up their capacity to handle the audience Blaseball had attracted, a process that includes both upgrading the website and hiring a dedicated web developer.

"We wanted to make sure that we gave just enough foundation that people can take it and run with it"

Stephen Bell

The team tells me they also used the break to get some rest themselves, as the game's explosion had led to concerns about their own workloads. And they also had to do some future planning work, with a mind to "steering the ship" a bit more with the game's narrative in the future. The team tells me that while they want to keep the "improvisational energy" the game's had so far, the growing size of its audience has prompted them to sit down and plan a bit further ahead for the different possibilities that could manifest -- though those possibilities remain, as before, at the mercy of the fan's bets, votes, and interpretations.

"A lot of it has come down to us just continuing to try to find interesting social interactions and experiences, by giving just enough seeds of narrative or putting the fans in a new situation where they might have to collectively rally or even just presenting opposition and antagonists to push back against," Bell says. "We have some definite ideas and themes that we've been expressing from the beginning and that are pretty clearly and plainly stated in the text if you're really looking at it, but we wanted to make sure that we gave just enough foundation that people can take it and run with it. And we can continue to keep it a dialogue between us and the community."

Clark adds, "I've been thinking of the narrative that we put into Blaseball like laying down a cool bass line. We're letting the community just riff and do their own solos over the top of it. It's just an easy track that anybody can jump on and start playing around with. If we were soloing on top of it, it'd be really hard for other people to join in.

"I think people's imaginations are so much more powerful than anything that we could possibly give them"

Sam Rosenthal

"If we see the community going a certain way, but people have different ideas about it, we don't have to cement any one part of that. We just have to start playing a baseline that kind of works with it, and then they'll find their way on top of it."

Blaseball is still a young game, but it's already proved a highly unusual example of how live games can interact with communities. I ask the team if the weird path their "side project" has taken had left them with any big or interesting takeaways, and Rosenthal comes up with two. His first acknowledges how different Blaseball is from Where Cards Fall -- it is, almost accidentally, exactly the kind of game the team was trying to pitch as its second title to begin with.

"We had a lot of really great feedback for Where Cards Fall, but Where Cards Fall is a game where the story allowed for you to impart a lot of your own experiences onto something that was quite a bit more defined, while Blaseball was not nearly as defined from the get-go," he says. "It was much more of this more organic play space where people can not just impart their own experiences, but really change what they believe it to be and show what they believe it to be. And that's a very different direction for game design. It's much more focused on procedural narrative rather than trying to map a set of game mechanics to a more authored narrative."

His second? Sometimes, limitations can spark greater creativity than unhindered possibility.

"I think people's imaginations are so much more powerful than anything that we could possibly give them," he concludes. "This is a game that by design has no real visual elements to it. And part of that came from us trusting the players. And part of that came from us knowing that if we brought an artist or an animator on it would cost more and increase the scope. And when you have to pull those things away and have to rely on your audience to fill them in, they can take them in very unexpected, more interesting places."