Lowering the language barrier for aspiring Arab developers

Fawzi Mesmar never had access to Arabic books on game design, so he wrote one

Fawzi Mesmar has always tried to help people understand games.

As the studio game design director at King Berlin told GamesIndustry.biz yesterday, "I was a nerdy kid, and when I was in school, I was so infatuated with video games I used to write strategy guides in my notebooks and distribute them in class to help other kids finish the game."

It was actually while writing just such a strategy guide for the original Resident Evil that Mesmar developed the first spark of interest in game design.

"I was tracing the mansion and saying where all the objectives, puzzles, and keys are," Mesmar said. "And I thought to myself as I was tracing it, 'Somebody must have drawn this mansion from their mind. They just came up with this. That's the coolest job in the world. I've got to be a game designer when I grow up."

"Really the only way for me to learn at the time was trial and error. I went with my best judgment and made a whole lot of mistakes"

There was only one problem. Mesmar was living in Jordan, an Arabic speaking country which at the time lacked both a strong development scene and Arabic language resources. So when he and a couple friends founded their own studio to work on a Game Boy Advance project in 2003, they were somewhat unprepared.

"Really the only way for me to learn at the time was trial and error," Mesmar said. "I went with my best judgment and made a whole lot of mistakes. It wasn't just me; it was the two guys I was working with. We were making mistakes all the time because we didn't know any better."

Nintendo had no official presence in Jordan at the time, so there was nobody to even go to for dev kits. The team managed to hack a few commercial Game Boy Advances to serve as dev kits, and actually cobbled together a couple levels of a 2D platformer before the entire team was hired away to work at a larger Jordanian studio, NASSONS. It was through that job Mesmar was finally able to make contact with Nintendo, while travelling to the Tokyo Game Show in 2006.

"They were more interested in knowing how we got our hands on video games rather than how we made the game," Mesmar said. "How did you know what Nintendo is when you're not part of the distribution chain? How did you get your hands on our games? How do you know who we are? It was completely outlandish for them to see three guys from Jordan fly all the way to Tokyo to try and pitch them a game."

Clearly, the industry at large was not prepared to foster development in a region of the world about which they knew next to nothing. Mesmar was hungry to learn, but there simply weren't any resources he could find in Arabic.

"I was privileged to get a good education and be able to speak really good English growing up," Mesmar said. "As I discovered what game design was and was fascinated by this world, I tried to get my hands on books to read more about the topic. Raph Koster's 'A Theory of Fun' was the first thing that introduced me to game design, and Jesse Schell's 'The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses.' Those two books are monumental in shaping my understanding of game design."

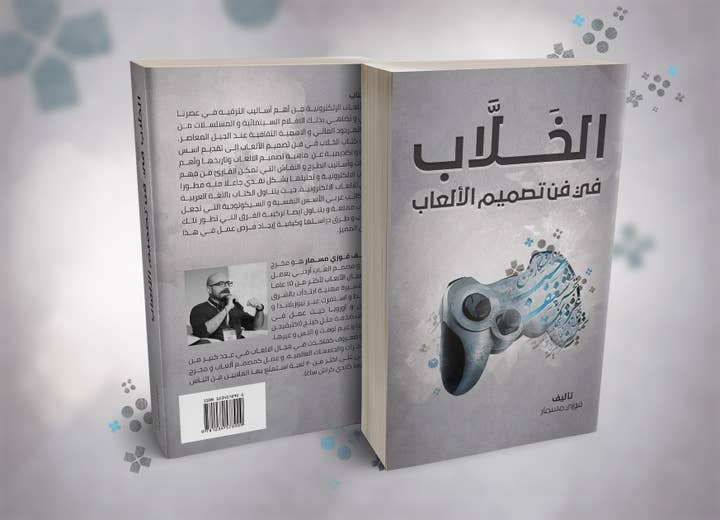

To this day, Mesmar's reading on game design has come entirely in English and Japanese. While he was fortunate enough to be able to learn both languages, he didn't think that should be a prerequisite for Arabic speakers interested in more in-depth writing on game design. For that reason, he wrote "Al-Khallab on the Art of Game Design," which launched for sale on Amazon last week.

Mesmar explained that Al-Khallab means "the spectacular" or "picturesque," but the name was chosen not so much to be grandiose as to fit a traditional rhyming convention in Arabic book titles.

"I'm trying to offer advice that I wish somebody gave me starting out. And at the same time, I'm trying to give people a shortcut, so they don't necessarily need to learn a foreign language to understand what game design means."

Mesmar believes it's the first Arabic language book on game design ever published, a status that presented a number of challenges he hadn't quite anticipated.

"I'm trying to give people a shortcut, so they don't necessarily need to learn a foreign language to understand what game design means"

"There are a lot of terms I'm used to working with in English," he noted. "If I'm writing this book, I'm going to need to translate these English terms, obviously. But because there's no book on this topic, I might be coining them at the same time."

It's possible to use literal translations of terms like game mechanics, emergent gameplay, procedural level generation, discrete game spaces, and rapid iteration, but each term has certain connotations English-speaking developers intuitively grasp at this point that could be lost in the process. Through his own assessment and in consulting with other Arabic-speaking developers, Mesmar attempted to preserve the connotations of each that would be most useful to his readers. He hopes that having access to such concepts in familiar language will benefit the Arabic development community at large.

"Most of the community is thinking about how to make games rather than game design," Mesmar said. "They're thinking about the technicalities of the game engines and the art and the budgets. Thinking of game design, analyzing games, and thinking of gameplay comes secondary sometimes, which sounds weird if you're thinking that these are people making games."

Even without his book, Mesmar has noticed the hurdles for developers in the Middle East getting lower over time. More companies have official presences in the region, more development tools are available and at least partially localized, and the dev scenes in Lebanon and Jordan are particularly active, Mesmar noted.

Still, that's a development scene Mesmar of which is no longer a member. In 2011, he left the Middle East for a job with Gameloft in New Zealand.

"I remember telling my wife that I didn't really care about how much I was going to be paid or what not," Mesmar said. "I just wanted to see how I measured up in an actual game development environment. People around me tell me I'm OK, but I want to be sure."

Mesmar has since built his career up working in Tokyo and Berlin. The hope is that with fewer hurdles to development and more resources like "Al-Khallab on the Art of Game Design," the next wave of Jordanian developers won't have to leave home in order to find success making games.