Little Hellions nearing deliverance after seven years

Jace Boechler shares two key decisions that helped bring their passive-aggressive fighter to the brink of release

Little Hellions began life as a game jam project in 2015. Developer Jace Boechler expect it to launch into Early Access in the fourth quarter of this year.

Speaking with GamesIndustry.biz, Boechler says they wouldn't recommend anyone plan on taking seven years to make a game, but they also can't say they regret having done it themselves.

"I wouldn't want to have released Little Hellions two years from when I started it because it would have sucked, frankly," Boechler says. "It wouldn't have been good. I would have been embarrassed by what I had made, whereas the thing I've made now, I'm really proud of. I'm really attached to it, and I think it stands on its own as its own thing, regardless of whether it's everyone's cup of tea or not."

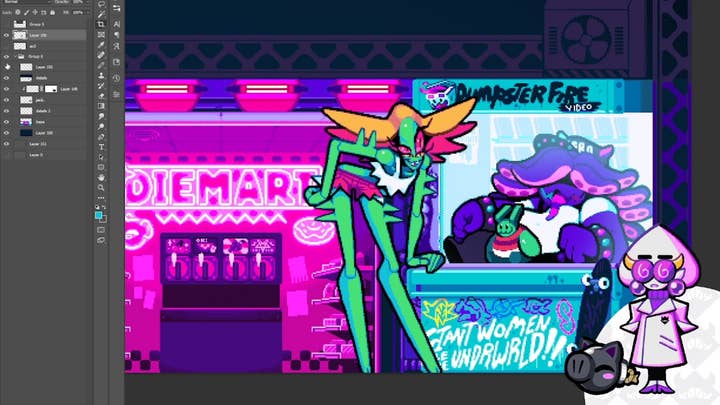

As for how they would describe that tea, Little Hellions is pitched as "the passive aggressive fighter where you can't fight": a four-player arena fighting game where you can't directly attack other players, so you have to put yourself in the path of one of the game's environmental hazards -- trains, lava geysers, bomb pigs, etc. -- and then use a Trick Hook mechanic to swap places with them at just the right/wrong moment.

While Boechler doesn't regret the time spent to get Little Hellions where it is today, they also are careful not to valorize it.

"I wouldn't recommend doing this to anyone," Boechler says. "This isn't how you make video games, I don't think."

They add, "I've been told that working on a game this long isn't all that different from working on your Masters degree or something like that, in terms of time commitment. I think there are a lot of analogies there. There's a lot of room for doubt with what you're doing with your project. You question a lot, like, 'Is this even good?' and things like that. There's also a lot of aspirational thinking that isn't very conducive to finishing a thing, if that makes sense. 'Oh, I want to add this and I want to add that,' but you need to make a thing that people can play and is a finished product. There's an endless amount of things you need to make your way through."

Developers of all stripes can likely relate to feeling like there's an infinite work to be done, and it's one of the reasons so many of them have had experience with crunch. While Boechler says they're a big believer in work-life balance, the realities of development don't always make it easy.

"Accountability is a really hard thing when you're working by yourself, so you push yourself in ways you wouldn't push other people," they say. "And that's really hard to program out of yourself, and I've only really figured out how to do that in the past couple years."

The past couple years have been key for Boechler and Little Hellions in a number of ways, including their transition from hobbyist game developer -- Boechler had a day job for the first several years of the game's development -- into a full-time professional.

The experience taught them a lot, even if a chunk of that was things they already thought they knew.

"There were definitely a lot of things I had heard and thought, 'Yeah, that makes perfect sense,'" Boechler says about the advice he'd received when first getting into game development. "And just like every life experience ever, you live it, then you come out the other side like, 'Oh, that's what they meant by that.'

For example, scope. The rule of thumb Boechler had always heard was to think about the scope of the game you want to make, then cut it in half, then cut it in half again.

"Being a young, naïve artist/game dev, I was like, 'I'm special though, so I can just do it,'" Boechler recalls. "And of course, after spending seven years on a thing, you're like, 'No. And I shouldn't have to do it. I'm allowed, and it's OK, and I'm entitled to cut things. It's all right. The ideas aren't that good.'"

They can actually narrow down the moment of revelation on that one, which occurred when showing Little Hellions to a friend of a friend who worked at Bioware, who asked why the game -- which already seemed plenty polished -- wasn't out yet. Boechler replied that they were working on a co-op mode that turned out to be a huge endeavor involving new characters, concepts, and complex systems to program.

"He said, 'Yeah, I see that. It's like you're basically making two games,'" Boechler says. "And as soon as he said that, I was like, 'Ah shit. I am making two games.'"

After some deliberation, they decided to cut the co-op mode entirely.

"I was worried at first, of course," Boechler says. "You spend six months plus working on something and you're like, all that time was wasted and the game's going to be lesser.

"But as soon as that seed got in there, I couldn't stop thinking about it. And once I decided to do it, I was massively relieved. It was instantaneous. As soon as it flicked in my brain that I was going to cut this, it was like, 'Wooooow... this is so nice. I don't have to make that now?'

"From then on, I was like, 'Wow, cutting things is awesome! This is great!' So I started cutting things left and right, and I think it's mandatory. It's required. It makes a better game, because when you cut something, it's not like all those ideas are gone forever and it's not in the game; you're just focusing."

Another breakthrough came in Boechler's efforts to livestream development of the game.

"The 100% largest struggle I've had as an artist and a game developer -- even after working on a game for seven years -- is traction, having anybody be interested in my project or know it exists at all," Boechler said. "It's been pretty insurmountable to do that. So when I started streaming, I was too focused on that. 'Oh, I gotta get people to get their eyeballs on this thing.' So I was doing streamer things, playing games sometimes and I had all this community stuff set up. But no one showed up, and I got discouraged."

After a couple months of streaming like that, Boechler changed the format. They created a cartoon persona to stream as, a mad scientist type of character named Professor Onion.

"That has been probably the most productive decision I've made regarding the project, unbelievably," Boechler says.

Freed from the pressure of entertaining and any kind of self-conscious distractions about appearing on camera, Boechler can focus more on developing a game. It also helps that Professor Onion enables Boechler, who values privacy, to distance themselves from the public face of Little Hellions.

Now they stream on Mondays to lay out what they're going to be working on that week, and return on Fridays to explain how that worked out (or didn't, as the case may be).

"It's weird because you're like, 'Seven years? That's forever.' But at the same time, to me it feels like it's going really fast"

"I have been massively more productive ever since I started doing that, and it's simply because of accountability," Boechler says. "I have other people who are paying attention to what I'm doing, so I have to do what I say I'm doing; it's not just me anymore. That has been really encouraging and an immense amount of progress on the project has happened ever since I decided to do that."

As for the traction and community that was the impetus for streaming in the first place, the stream still doesn't seem to be moving the needle on that, with just a handful of people watching Professor Onion on a regular basis. Still, Boechler isn't bothered by it.

"I don't really need people in the chat to motivate it," they say. "It's a structural thing, like, 'At this time on this day I will work on this and then at this time on this day, I'll report on it. It structures my whole week almost. In a productivity sense, it's not so much about the Twitch numbers. I have a schedule to keep, and it's nice to be able to show those people how things have come along, whether it's a large number or a small number."

Between the adjustment of the game's scope and the productivity boost of streaming, Boechler says the game has come together in a hurry.

"It's weird because you're like, 'Seven years? That's forever.' But at the same time, to me it feels like it's going really fast," Boechler says. "It's taken so long up 'til now, that now that I'm on a good pace, it's like, 'whoa whoa whoa...'"

Now Little Hellions appears to be in the final stretch of development. Whenever it hits a 1.0 release on Steam, Boechler plans to bring the game to consoles. After that, they're looking to take a break, perhaps pursue some projects away from game dev as an illustrator, and then start working on the next game.

The plan is that it will not take another seven years.

"This isn't how you make video games, I don't think," Boechler says. "The average project should be two to three years, tops. Ideally even less than that... I'm going to start with the scope on this one, and make it the most honed, specific thing I can make it."