Ken Williams doesn't know how his design philosophy could work today

Sierra On-Line co-founder talks about his new book, disconnecting from the games industry, and what's changed since he left nearly 25 years ago

We've interviewed a number of authors at GamesIndustry.biz over the years, but few have been as candid as Sierra On-Line co-founder Ken Williams when we've asked them why they wrote their book.

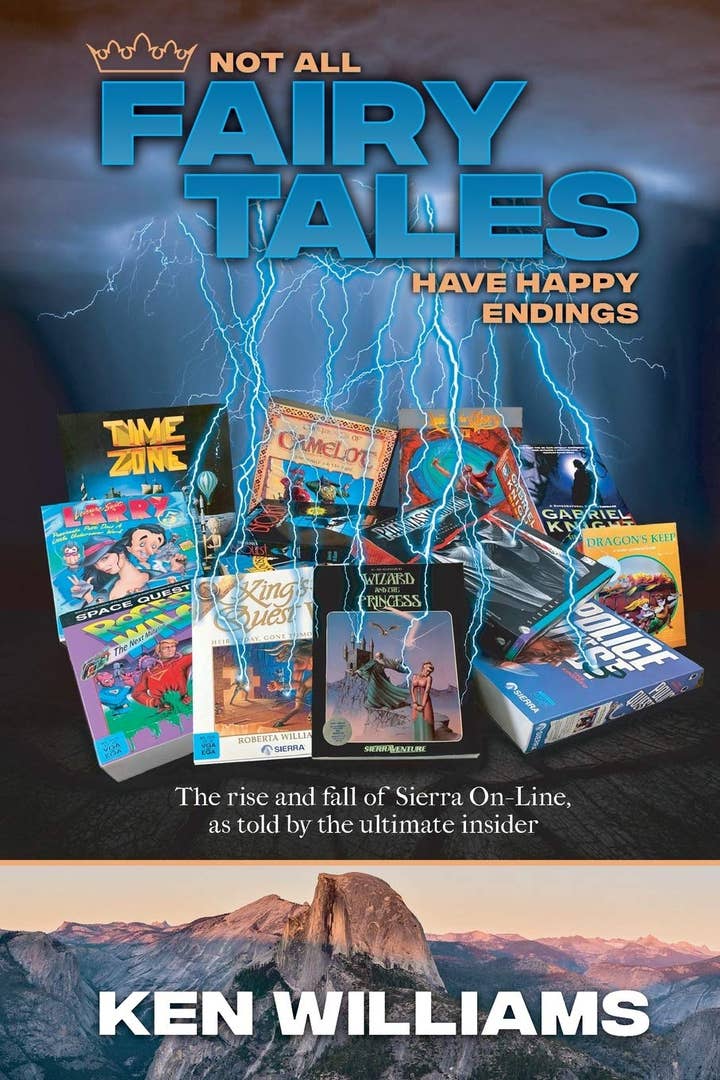

"Boredom," he gives as the primary motivation behind "Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings," the book about his time running the adventure game publisher with his wife and Game Developers Choice Pioneer Award recipient Roberta.

"I actually did not want to write a book," Ken explains. "For like 25 years, everybody bugged me saying, 'Please write a book.' And I always said, 'No way in hell.' In January if you asked me if I'd ever write a book about Sierra, I'd have said, 'No chance.'"

But then the COVID-19 pandemic happened and Roberta suggested he write a book. He considered fiction and other non-fiction subjects, but the old adage is to "write what you know." And judging from Ken's previous books, what he knows is boats.

"What happened was when we sold [Sierra in 1996], we bought a boat and Roberta and I began a new life as world cruisers, kind of taking our boat around the world," he says. "We took it through 27 countries, across the Pacific and the Atlantic. I got a captain's license, and we're actually more famous these days as boaters than we are as computer game alumni."

But having already written about boats at length, Ken turned to the other subject he definitely knew well enough to write about: Sierra On-Line.

Ken readily admits that he's "pretty much disconnected" from the modern games industry, but he's well aware of how much it has changed. He's noticed the broad resurgence of interest in older games, whether they were made by Sierra or not.

He's also noticed the difference in how seriously the world outside games treats the business now.

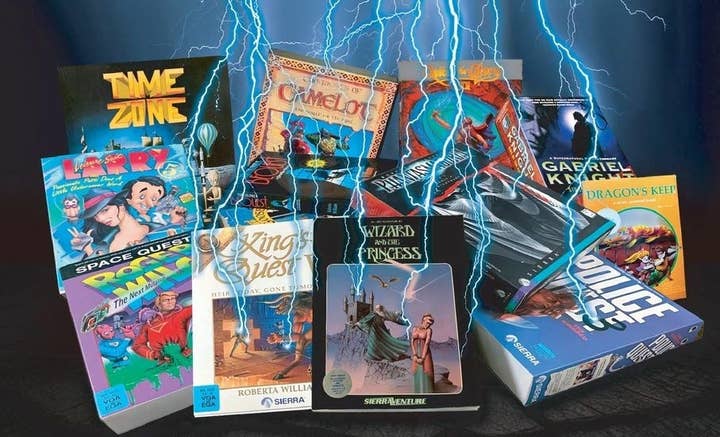

"I think the connection between serious entertainment in the game industry is now recognized as a real industry and big money. In those days it was nothing. It was hackers and kids and floppy discs."

He recalls how strange it was at the time having a Hollywood agent approach him at Sierra saying movie stars were interested in appearing in his games. (These days Hollywood agencies have staff dedicated to representing game developers.)

"All of a sudden, the games business was hot and perceived as the next big fad," Ken says. "It was becoming apparent to Hollywood that there was really going to be some money in the games business someday and they should start getting their name known... It was a waking up that there was an industry here. It was a cool time to be in the business."

Ken's status as a celebrity developer at the time came with some rare experiences. He visited John Travolta's house to show him a game one time. He had Todd Rundgren call up wanting to do music for a Sierra game.

That may seem quaint compared to the cultural capital of current celebrity developers who are celebrated on The Tonight Show or wind up as fodder for TV series, but it sounds like about the level of fame Ken is comfortable with. He's aware of the extent of harassment prominent developers have dealt with in recent years (doxxing, bomb threats, etc.) and wants no piece of it.

"It's good we weren't at that level yet or Roberta and I would have no lives left," Ken says. "I definitely like what level of anonymity we have."

At the same time, he's seen how the role of the prominent developer has changed since the days of Sierra On-Line, and he also seems a bit relieved to have missed out on much of that.

"The first games were just Roberta and I," Ken explains. "When we sold the company, most of the projects were probably about 25 people, but Phantasmagoria probably had 100 people on it. Budgets were starting to get bigger, but nothing like today.

"One of the themes of the book is the way I did projects was to have an idea for a category I wanted to be in, then to watch for somebody who was passionate about it. Then my job was to somehow protect their passion, because everybody on a project wanted to put some piece of themselves into the game."

He adds, "And if suddenly I've got 100 people working on the project, then my goal is how to get the other 99 people to just do what they're told and shut up and not try to filter their personality into the game. How that could be done with 1,000 people, I don't know.

"One of the biggest philosophies I had was that the designer had to approve every piece of art, every piece of music, every piece of copy. And I don't know how you do that on a 1,000-person game. Then suddenly it becomes a game and not a work of passion. And I had problems with that as the company grew."

Ken says his vision was that playing a game should be like having lunch with the designer. If Sierra On-Line was making a history game, Ken wanted a creative lead passionate about history who could entertain you for hours just talking about history, because that had to come through to the customer.

When he left the company after selling it, Ken says that vision changed in a hurry. Roberta stayed behind to do King's Quest 8 and found the company's development philosophy notably different.

"She was viewed as the designer, just 'Give me your design and go away, and we'll build the game,'" Ken says. "That was a whole different philosophy than what I did, and suddenly the game that came out didn't feel like you were hanging out with Roberta. It just felt like a game. And that was kind of the worst of all the King's Quests."