"It's the software that matters, that's it"

Fireproof Games' Barry Meade on how a focus on business and marketing can be detrimental to a game developer

Fireproof Games' Barry Meade took the stage at Game Connect Asia Pacific (GCAP) to discount the importance of business in game development. The makers of the hit iOS puzzle series The Room have sold over 10 million copies across two games, but they only ever worried about making a good game.

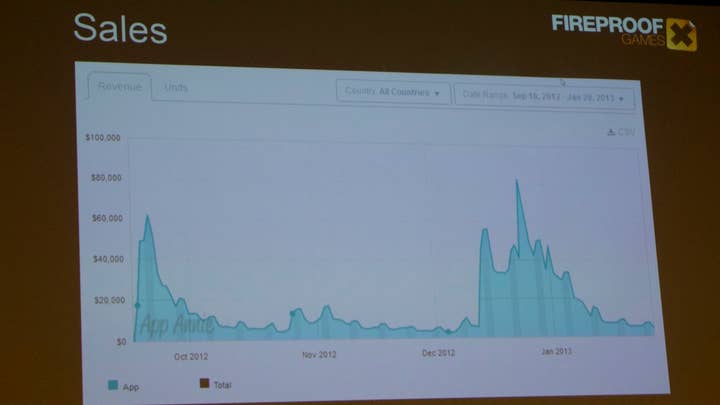

"To this day we've never spent a single cent on PR or marketing," Meade said. He credits their financial success to Apple, which featured The Room upon release and awarded it game of the year, and to word of mouth. Indeed, the bulk of the game's sales came during or shortly after Apple's App Store displays, and the game of the year feature came as a total surprise.

As did any sales at all. The Room was intended as something of a portfolio piece to impress publishers who until then had been unwilling to take a punt on the former Criterion artists with anything other than contract work on other people's games. The six of them had managed to save £100,000 over four years as a specialist house in outsourced design and research and development work, and their plan was to have one of them work full time with a programmer for a year on mobile games while the rest continued doing contract gigs.

The Room came out of their second mobile prototype, which was based on a Chinese puzzle box. After six weeks of development, Meade took it to Apple for a demo. He'd heard of other developers receiving harsh feedback, but the Apple representatives simply told him to keep going. It was good.

That knowledge and confidence in hand, Fireproof remained skeptical that The Room would break even. Meade described that as a "sort of stretch goal." They'd seen too many talented teams with similar levels of experience to them struggle to sell apps; "We had no reason to believe any different," Meade said. "And we had been told over and over that the mobile market is this way."

"I can't tell you how many [game] conferences I've been to where the focus is just on business. These guys are not necessarily doing well. They're giving themselves heart attacks, and they're failing"

But the fact that it did break out and find a big audience he pins down to their approach and their ignorance about mobile development. "We didn't really know what we were doing," he said. "We had to learn how to make a mobile game at the same time we were doing it." But more importantly, The Room was something they cared about. They're proud of it. "It was very important to us to make the game that we thought mobile games could be," he explained.

"We thought people just weren't trying very hard, frankly. They were giving in to the mountains of data that hammered down what a mobile game should be." As self-described hardcore gamers, they wanted The Room to be a mobile-tailored experience that would speak to people like them, and they believed that marketing would be pointless to these ends because they don't look at ads and they aren't influenced by anything other than word of mouth.

"We kept hearing all this stuff about what it takes to be a developer these days," Meade continued. "You have to be brilliant at PR and great at marketing and awesome at interviews and you have to go to all the shows and be doctor awesome at everything. But we never recognized that as being important to us because it's the software that matters. That's it. There's nothing else that's going to convince you to play other than how good it is."

Meade appreciates that marketing can and does work for more casual-oriented games, but he suggested it's irrelevant to games like The Room. Instead of worrying about business, he argued developers - especially those with small teams and limited resources - should focus on making good games. "I can't tell you how many [game] conferences I've been to where the focus is just on business," Meade said. "These guys are not necessarily doing well. They're giving themselves heart attacks, and they're failing."

The Room succeeded in spite of its lack of marketing and unspectacular press reception because it stood out as different and was the best game that they could make. "If we'd tried to be like other people," Meade argued, "[or] if we'd tried to play to a perceived audience, which the data says exists, it wouldn't have happened for us."

Find what you're good at and create your own niche, Meade said, because if you're indie you can't compete with the big guns like Clash of Clans or Candy Crush: "If you line yourselves up with those people, you are in for a hiding."

"If you try to copy what other people are doing, there are a million people in the queue ahead of you, and they [probably] have more money and they care less than you," he concluded.