Imagination Vs. Immersion

Kim Belair on the shift from playing 'with' to playing 'as'

Come dream with me

Recently I was replaying Super Metroid, which I'm fairly certain is the opening sentence to one out of every four introspective video game articles. I was in Norfair, on my way to fight Crocomire, when a creature emerged from the wall above me, armoured and eyeless, and spewed a fireball into the darkness. It missed me, but I couldn't be sure it intended to hit me at all, or whether it could even detect my presence. It is possible, given the strangeness of this hostile planet, that I was inconsequential to its routine, and it would have behaved in this way whether or not I had stumbled in. I had no idea. I don't know what triggered it. I didn't even know what it was. But I had the distinct feeling that Samus did. There was no doubt in my mind, even as I moved her nervously and frantically through increasingly treacherous environments, that she knew her mission and this world better than me, and whatever fears I had were entirely my own. I was with her, but I was not her.

And that's interesting. I mean, at least to me. Because in order to experience the dread and the isolation of the 16-bit world before me, I had to imagine what Samus was contending with, what she was seeing and what she might know, without experiencing it myself. The onus was on me to take a relatively crude assemblage of pixels, and envision something more. What the game was asking me, as a player, was to bridge the gap between what they showed me and what they wanted me to see. With our limited technology, we couldn't achieve the kind of immersion that's become an industry norm in 2016, and so we relied instead on imagination. If we couldn't show the player what we saw in our minds eye, we could ask them to come and dream with us.

Filling in the blanks

See, we never drew in pixels. I'm kind of obsessed with that. In the manual for Super Metroid, the boss monsters are rendered in all their comic book glory, all curves and shadows, and Samus herself is a blend of metal and glass in dynamic poses we'll never see in the game, leaping off the page. The emblematic crest on the cover of The Legend of Zelda is far smoother than any of the icons it represents. Even the character designs for a game as colourful and evocative as Earthbound, notably, were 3D, built out of clay. In the end, all were reduced to pixels-beautifully of course, as I am trying to use 'reduce' in as non-reductive a way as possible-but we understood that we were meant to see beyond that. Developers were building worlds and devising ways to share them with us, and what they asked was for us to meet them in the middle. In a sense, video game art at the time was akin to elegant translation: something may be lost along the way, but the new language had a beauty and nuance of its own.

"Developers were building worlds and devising ways to share them with us, and what they asked was for us to meet them in the middle. In a sense, video game art at the time was akin to elegant translation"

Many of the backgrounds in Super Metroid are black. A few bits of suggestive rock, some curious machinery, a hint of colour or gradient, but beneath it and outside it, black. The advent of parallax scrolling meant that our characters could inhabit a world with some depth, but that depth was generally a repeating pattern, extending into infinity. This was crazy. The jungles in Donkey Kong Country went on forever, home to a thousand creatures and thrilling locales we would never see. Sonic's Green Hill Zone was seemingly bordered by a dark mountain range we would never explore. Today, we still use these "natural" borders (mountains, dense forests, high rock walls), but within them, we've become accustomed to spotting something interesting in the distance, dropping a waypoint on it, and making our way there to sate our own curiosity. This is, in itself, an incredible freedom and something that dazzles me in something like Red Dead Redemption or while unlocking a coveted shortcut in the interconnected paths of Dark Souls, but it's a different form of engagement. The world feels more real, yes, but-if this is possible-simultaneously more expansive and much, much smaller.

I brought this idea up to my art director recently, that the emptiness or vagueness of old games' landscapes contributed to a very dreamy atmosphere. It made us wonder rather than expect. Thoughtfully, he compared it to the difference between a sketch and a finished piece, and the fact that people often prefer the former because it allows them to imagine what might be there, and follow the rough lines they prefer, rather than the ones given to them. They can still be surprised.

Your Character and You

One of the most notable surprises in video game pop culture is the reveal of Samus' gender at the end of the first Metroid. What fascinates me about that is that it isn't a twist, or a deceit of the player. Yes, it played against our expectations of what a video game hero tended to be back then (a dude), but it's simply a fact to which we weren't privy. Samus knew all along who she was, but only in accompanying her on this journey could we learn more about her. The character, for as much time as we played her, was not us. She was her own entity, and that was how we engaged with games at the time.

"Samus knew all along who she was, but only in accompanying her on this journey could we learn more about her. The character, for as much time as we played her, was not us"

This isn't to say that the characters we play now don't surprise us. Nathan Drake revealed an estranged brother in Uncharted 4, Call of Duty: Black Ops offers hallucinations as truths for a great deal of the campaign, and Bioshock's big reveal undoes an entire game's worth of player agency. The difference here is the way we justify it: we either retcon, expand backstory, or use madness and outside influence to explain why our playable characters failed to show all of themselves to us. Anything else would break immersion. Immersion is about putting ourselves inside of a game, being surrounded by it, and getting lost in it. As gaming has evolved, our relationship to the protagonist has changed from playing with to playing as (not that we ever called it that-that would sound super weird). With many games in the past, we told a simple story, gave a character a stark but sturdy identity, and then asked the player to accompany them from point A to point B. If you were lucky, you might even get a "THANK YOU!" screen at the end of it all, featuring some cast members applauding your efforts. If, today, at the end of Arkham Knight, Batman turned around, grinned and said "Thanks for playing", we wouldn't know what to do with ourselves. The 4th wall is rock solid.

But what does that mean? I promise I'm not campaigning for more protagonists winking knowingly to the camera here, and I love nothing more than spending an hour on character creation to ensure I get the optimal chin height or eyebrow width, but sometimes it can feel as though the cost of immersion is faith. With the player ensconced deep within a simulation, the slightest flaw becomes a jarring and unwelcome bit of reality. It becomes more difficult to watch our character make choices that don't jibe with our own, or to accept that we just can't swim past that invisible wall.

The Big Picture

So if at one time, tech limitations meant we had to ask for the goodwill of our players, and to invite them to believe in what we were telling them, advancements in technology have meant that we need ask nothing of them but to look at the world we've made, and to live in it. Our concept art requires no "translation": we can replicate it all in-engine almost perfectly. Our characters tend toward the extremes: either they are so well- and clearly-defined that the player contributes nothing but movement, or else they are so loosely and vaguely drawn that the player must give them the personality they lack (The "Silent Protagonist"). The player doesn't need to use their imagination because we did all the work for them, be it simply because we can, or out of the deeply human desire to tell a story and be understood.

"Beyond the lure of nostalgia, there's a reason that most indie games more closely resemble older titles: limited means create 'limited' experiences"

I mean, it could also be money. Games aren't cheap. Independent studios often hope to break even at best; their motivation is strictly to get their art out into the world and have people experience it. Beyond the lure of nostalgia, there's a reason that most indie games more closely resemble older titles: limited means create "limited" experiences, and players are more likely to offer them the break that AAA titles can no longer ask. Stepping into the world of something like Toby Fox's Undertale, we can imagine how Papyrus and Sans might sound or speak, hear our own mothers in the voice of Toriel, and guide our aloof little protagonist through some very unlikely situations. We're imagining what these places might look like to our eyes, and often the work of constructing our own mental images creates something akin to a "mind palace": a collection of memories we can easily visualize. I compare it to a recommendation I received when I realized I was forgetting people's names immediately after an introduction: if they tell you their name, you'll forget it, but if you speak their name back to them, you're more likely to recall. Asking for that additional input from the player is a type of engagement that creates memories rather than anecdotes. But, backwards as it sounds, it's not always something bigger companies can afford.

If you see concept or even marketing art for an old SNES or Genesis game, or an independent title today, and it shows the vision of the creators rather than the actual product, we can be inspired and begin to dream along with the teams behind it. Lately, though, if an overly-polished CG trailer or lavishly illustrated poster for a AAA title seems at all disparate from the finished, playable product, we're quick to call it a downgrade at best, a lie at worst. We expect a certain kind of game to be delivered to us, and that is one that is fully-formed, that does what it says on the tin. This isn't a problem, per se-the increasing power of immersion and the push toward VR mean that we'll only be getting deeper into virtual, hyper-realized worlds-but it does mean that more subtle or more minimalistic worlds and designs might be increasingly difficult to sell, and protagonists and player one and the same. They don't really need to dream, when they can simply live.

Goodbye to all that

Old games aren't better than new games. They're different. It's easy for me, at thirty, to fall into the trap wherein I romanticize the games I played as a kid and let myself become so jaded that I dull the shine of the games I play now. The reality is that we're still making incredible works of art, regardless of their scale, and whether we experience those as dreamscapes and imagine our way into them, or explore a fully-realized environment built for us, there's magic there. Ultimately, my yen for the relationship I had with a game like Super Metroid is simply a pull toward a kind of satisfying, maybe old-fashioned engagement that was once more commonplace. And I wonder, maybe idly or selfishly, if we can't find a way to bring more of that back.

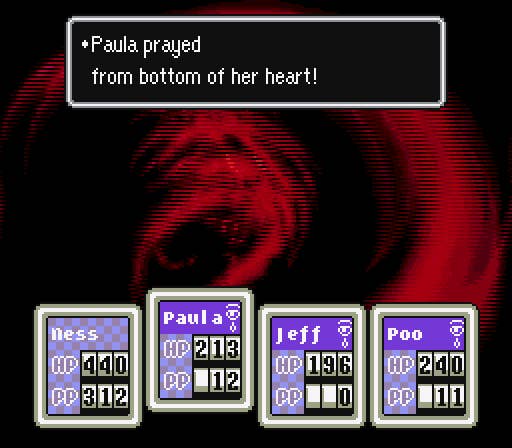

There's a point at the end of Earthbound, during the final battle against "Universal Cosmic Destroyer" Giygas, where the characters, four children from different parts of the world, have exhausted their abilities and must literally rely on the power of prayer. Now, earlier in the adventure, in a cute little trick, a kid named Tony phones the protagonist and says he's collecting players' names for a school project. He clarifies that he means players just like you, "the one holding the controller", and you register your name with him. It's something quick and forgettable, until Ness, Paula and friends are up against the final boss. He is too strong for them, too monstrous, and despite their best efforts and all the powers they have gained, it becomes clear that this is a fight they can't win. And so Paula begin to pray.

The screen goes dark for a moment, but then opens on some of the NPCs they've met along their journey, and those NPCs begin to pray for the safety of Ness and the gang. Giygas' defences falter. As Paula keeps praying, we see other people they have helped, we see their loved ones, their families, all praying for the safety and well being of these kids who touched their lives. Giygas is weakened. Finally, Paula runs out of people, realises she has thought of everyone she knows, everyone who cares. Into the darkness, she calls out for "someone" to give them strength. And against all odds, she gets you. The player. "The one holding the controller". You've already led them through the toughest battle of their lives, and now they just need you to believe in them.

I remember sitting there, as a kid, and earnestly hoping. Sending my prayers out to these pixels, and imagining that I was helping. I've never been so aware of myself as a player, outside of a game, but I've also never been so deep within one. It was pure belief and precious little immersion-at least immersion as we've come to define it, but that was okay. And it's still okay when I play it as an adult, because I'm happy to dream with them. These kids weren't me, any of them, but they were my friends, and I was willing to do the work. All they had to do was ask.