"I'm tired of shooting people for no reason other than not getting killed"

Eat, Create, Sleep on ambition, religion and asking tough questions

Early on in my chat to Martin Greip, art director of Eat, Create, Sleep, I can tell I've said something painful. It's an occupational hazard, and not something you always try and avoid, but this wasn't intentional. He's too polite to really show it, but I think I may have touched a nerve.

With hindsight, I can understand it: I've compared his studio's latest game, colourful polygonal god-sim Crest, to Godus.

It's not really a fair comparison, something which becomes more apparent when I play more of it later, but I'm not the first to make it, and there are some common themes. Both are bright strategy titles where the player exerts indirect control over a population, encouraging them to build and expand. They're both procedurally generated, presented in in an overtly stylised manner and each spent a formative period in Early Access. Still, Greip isn't fond of the comparison.

"Let's just say that all of the comparisons to Godus didn't work in our favour..." he sighs.

It's an easy, if somewhat lazy, juxtaposition to make: the sort which journalists are fond of. Alongside the similarities in the game itself, Crest was pushing through a crowdfunding campaign back in 2014, when Godus' promises were beginning to fall apart, but Eat, Create, Sleep have responded in a very different way to the challenges presented by development, embracing an open dialogue with Early Access players and IndieGoGo backers. In December of 2016, after we'd spoken, the team published a frank and honest blog update about the mistakes along the road, as well as the positive view they have of the game's future. It's a good read, and contains a lot of lessons for anyone looking to take this particular route to market.

But the small Swedish studio is also a little harsh on itself. Crest is a game with a great deal of depth and scope, which seems to have moved consistently in the right direction in its 20 or so months in Early Access. It's also a refreshing take on the genre, offering an interesting perspective on the evolution of religious truths and the social interactions and conflicts which they can facilitate - an investigation of divine will which focuses on the trickiness of absolutes once mortals get involved. As Greip tells me, there's no way to win - it follows the Dwarf Fortress model of 'play until you inevitably die' - but he explains that it's not belittling faith.

"If we're making any statement, it's that's extremism and short-sightedness are bad. I guess that could be indirect criticism of religion"

"Some other developers we speak to have said that Crest is a game which criticises religion, that we think people who have religion are stupid, but it's not and we don't," he says. "If we're making any statement, it's that's extremism and short-sightedness are bad. I guess that could be indirect criticism of religion. But it's more about looking at how religions function, particularly with the way that the commandment system can corrupt over time. It's sort of wish fulfilment, how religion evolves as people deal with new situations, how something written a thousand years ago might come to mean something completely different."

Commandments in the game are issued via an innovative sentence system, with components formed from various action, object or place related words, acquired from the environments of your worshippers. So the words for 'savannah', 'produce' and 'baby' will result in people who live on the plains making more worshippers, whilst 'farm', 'don't consume' and 'ostrich', will stop the followers who live near agriculture from hunting ostriches.

It's a flexible and intelligent system, but initially a little frustrating because of the inexactness which is its very focus. Once you're over that, it makes a lot more sense and you can start issuing more advanced commands, like the urge to migrate and create new villages. However, that brings its own complexity - the evolution and embroidery of edicts, and conflict between your worshippers.

"I'm very interested in history," explains Greip. "At university I studied a course about ancient Mesopotamia, which sort of inspired Crest. Even though the game is based in a fictional place in Africa, it's inspired by the city states which worked against each other in Mesopotamia. They (places like Nineveh and Babylon) arose at the same sort of time as ancient Egypt, with separate city states sharing a culture and pantheon. Each city ended up with its own patron god. The high priest of each city basically said 'we're the stewards for the gods. We till the ground and make a bountiful harvest to honour our god.' After a few hundred years these high priests were made saints, more or less elevated to the status of gods. Hammurabi is a famous example of that.

"Then, some of those priests became kings and started thinking 'maybe I should make myself a god before I die?' So after 500 years or so they became god kings, which I thought was a fascinating evolution, or corruption, of doctrine. Human ambition always sidelines compassion and faith. So Crest is basically an examination of that.

"It's sort of like raising children - you set out the rules and they try to find the loopholes to do what they want without exactly breaking them"

"It's not saying it's wrong, it's just part of our history. It's a historical religious simulator. Crest is really for the people who don't understand why religions can have seemingly inconsequential or stupid laws. It's sort of like raising children - you set out the rules and they try to find the loopholes to do what they want without exactly breaking them."

Guiding the inhabitants of your sunny island quickly becomes focused on managing the ever-expanding list of commandments you've issued and the gradual associations they start to make with them, justifying new behaviours based on their interpretation of what you've done before. Each village will gradually become aligned with more generalised doctrines, ways of thinking like materialism or martial discipline, which will guide those decisions and eventually cause them to be at odds, sometimes resulting in war. But, unlike nearly every other strategy game, you're not trying to wipe anybody out.

"There aren't any other gods," says Greip. "When you start, your people are all of humanity, and then they migrate from your first settlement and form other cities. You rule them, but you're not a dictator. Again it's like being a parent - we want it to feel like the city states are bickering children. Even when they're trying to kill each other, no parent is rooting for one to kill another. When you see two states trying to kill each other, we want you to feel disappointed, even though you can try and initiate war.

"The player never wins by killing off half of humankind. There are no win conditions. We examined this really closely - what's the biggest obstacle to a player feeling like they're creating a story? A single victory condition - because then every action is leading up to that. They don't feel like they're exploring their own story."

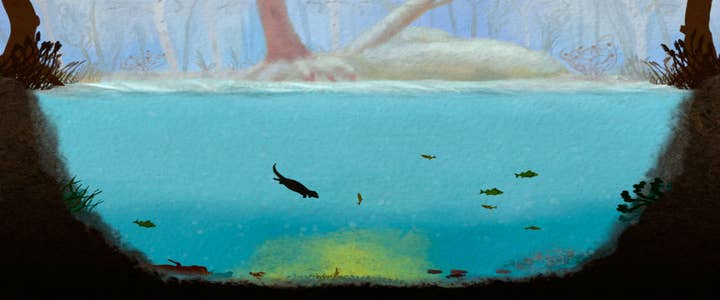

It's an interesting approach, and Crest needs a little more polish to fully realise its promise, but Eat, Create, Sleep is brimming with ambition and talent. It's only previous game, Among Ripples, was a pond-based resource management toy, where players introduce various species to a small lake, trying to balance their desires and consequences. It was released on Steam for free, with no monetisation whatsoever and achieved "something like 200,000 downloads in one month without any marketing."

Among Ripples was a short form game, and Crest is also aimed at one or two hour play sessions. That's partly something born of budgetary necessity, but also with the schedules of busy people in mind. For now, it's going to be a defining aspect of the team's work, alongside that ambition and desire to approach big issues.

"In future we might make longer games - maybe ten or twenty hours, but the core of the kind of games we make is something Will Wright said about wanting to give people the 'understanding of a concept' by playing his games. I thought that was a great explanation and we want something similar. Our slogan is that we make games about difficult questions and let the player explore the answers.

"Personally I'm kind of tired of all the games that don't really have anything to say. They're often sanitised so they don't offend anyone. I'm not even that old yet, but as a 27 year old I'm tired of shooting people for no reason other than not getting killed. I think that demonstrates how far big budget games are estranged from the real world."