"If we're going to be drug dealers, let's not literally mine for addicts"

At Reboot Develop, indie publisher Mike Wilson used the game addiction debate to call for devs to "be intentional" about what they create

As questions over the addictive properties of video games continue to swirl, Devolver Digital co-founder Mike Wilson has asked developers to "be intentional about what we're feeding our friends, ourselves, the general public, young people at their most vulnerable state."

Speaking at Reboot Develop Red in Banff, Canada this week, Wilson referred to the New York Times Magazine cover story from the preceding Sunday. The article -- titled "Can You Really Be Addicted To Video Games?" -- explored the difficult questions that have been asked of the games industry recently, by institutions like the World Health Organisation and various governments around the world.

"Can it be real? Is it a real thing? And a lot of that argument is just about words," Wilson said to the crowd at Reboot Develop Red, the European conference's first event in North America.

"We're where people are turning in their most vulnerable moments, when they're feeling their lowest"

"It's an academic debate on whether it's an addiction or a compulsion or just a hobby. But the fact is -- there's no debate about it -- that half of Americans...are playing games now, and half of those are playing more than 20 hours a week. And another chunk of those -- one in eight [people] -- would call themselves a legitimate addict."

Wilson's keynote talk was an account of his entire career, from working at id Software and Ion Storm in the '90s right up to the foundation of Devolver Digital and Good Shepherd in the last ten years. The narrative was one of self-discovery, and a growing awareness of the problems that developers face in creating games and navigating the world of big business and online outrage.

A turning point for Wilson was the rapid rise and fall of Gamecock Media Group, a publishing label with a somewhat abrasive collective persona that involved wearing capes and masks and lampooning the games business. The intention, Wilson said, was to "poke fun at the industry," but it did so "not in a fun way."

"We were bullies," Wilson said. "We were angry. I was angry."

Gamecock made a lot of noise, but it reached the end just two years after it started, when the 2008 financial crash scared away two of its major investors. Gamecock was acquired by Southpeak Games in October 2008, and Wilson expressed no regret at the premature end of his plans for the company.

"To be honest, it needed to be cancelled," he said. "It was not a good message to stand on -- 'you guys are all idiots.'"

"If we're going to be drug dealers, let's not offer them crack-cocaine. Let's not literally mine for addicts"

The collapse of Gamecock led to the foundation of Devolver Digital, a publisher that, perhaps more than any other, has helped to define the modern indie games market. In the course of working closely with small teams, Wilson said, he became more and more aware of the mental and emotional strain involved with game development. Four people Devolver was working with were hospitalised in the space of a year "from the stress [of finishing a game] and the relentless abuse now offered to them via Twitter."

Wilson helped to found a second indie label, Good Shepherd, as a direct response to the problems he saw in the industry. He also joined Take This, a non-profit organisation that tackles mental health issues among both game developers and gamers. As such, Wilson is alive to the kind of concerns being put forward in the discussion around game addiction, and he is less ready to dismiss those concerns out of hand.

"We're feeding the country, we're feeding the world, and we choose what we put into our creations -- which are often the result of what we've been fed," he said. "We are the pharmaceutical companies.

"We're where people are turning in their most vulnerable moments; when they're feeling their lowest, or they're feeling like a piece of shit, or life isn't working out as it should, because we live in this winners and losers society that is based on all kinds of things that are almost impossible to achieve for young people now.

"I'm not saying I have the answer... All I'm asking you to do is listen to my story and think about what we're feeding people. Just be a little bit more intentional. Whether you think these are drugs -- and by the way, I'm not against drugs at all -- but if we're going to be drug dealers, let's offer people psychedelics. Let's offer people something that's going to help them expand and grow. Let's not offer them crack-cocaine. Let's not offer them meth. Let's not literally mine for addicts.

"Even pharmaceutical companies would never use terms like 'user acquisition' and 'monetisation'"

"Even drug dealers, even pharmaceutical companies, would never use terms like 'user acquisition' and 'monetisation.' Now I'm sure there are great ways to do those, too, but I'm not familiar with them. And I don't intend to become familiar.

"Are we, collectively, gonna get our shit together and be intentional about what we're feeding our friends, ourselves, the general public, young people at their most vulnerable state? Then who's going to do that? Are we gonna leave it to the casino bosses? Are we gonna leave it to the people talking about user acquisition and monetisation? Are we gonna try and compete in that game?"

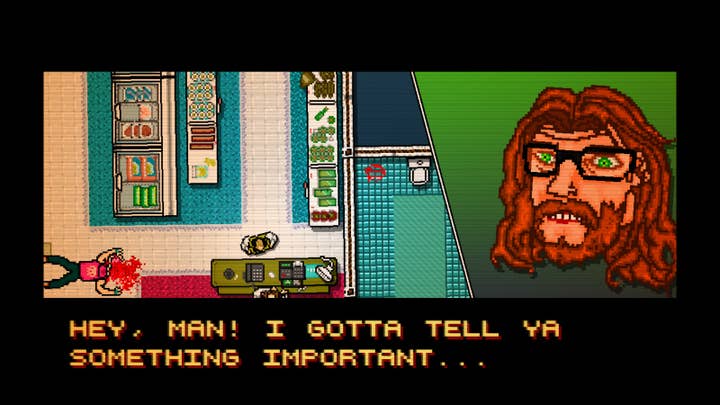

Wilson insisted that he was not criticising all "shoot-em up games," not least because he has benefitted from the sale and success of that kind of experience. However, he also pointed out that even a game as violent as Hotline Miami still contained a very clear message about questioning the mindless carnage in so many video games, and deliberately set out to make the player feel uncomfortable in their own complicity -- an example of the difference that being "a little bit more intentional" can make, even when the subject is death and destruction.

Right now, though, Wilson is devoting time to creating games "that feel a little better to me," and are separate to his work at Devolver and Good Shepherd. These games, he said, "are about bringing people back together. They're like those little LAN parties, back when people weren't so mean to each other. [They're about] nourishing people, and reminding them that it's going to be okay."

One of those projects is Transcend Victoria, based where Wilson lives in Victoria, British Columbia, which creates "immediate, interactive art" designed to bring people together in shared physical spaces.

"Because people are pretty fucking cool in person, as you may have noticed over the last couple of days here," Wilson concluded. "Just not so much online."

For the record: This article has been amended wth a slight correction to one of Wilson's quotes from the talk.

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner of Reboot Develop Red. We attended the show with assistance from the organiser.