How to build a Bandersnatch

Developers shares advice on how to create interactive movie games that can stand toe-to-toe with Black Mirror's latest

Following the success of Netflix's Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, we spoke to the creative minds and companies that have already been making interactive movie games that explore a similar premise.

Yesterday, we discussed whether Bandersnatch's popularity is likely to drive fresh demand for such projects. Today, we break down their tips on how to develop a title that satisfies that demand.

Story first

Tobias Weber, director of Late Shift, stresses that "a good story is the most important factor", as well as "a main character people can relate to."

The Bunker producer Simon Sparks agrees: "You need to start with the story. Do not think about your mechanic or design loops, do not even think about your execution at all until you've got a story worth telling.

"Games developers are without a doubt the best people at creating universes, but we need to spend more time focusing on complex characters, giving them flaws and weaknesses, and creating conflict and drama that is not about shooting people. It needs to go up a level.

"Getting used to iterating the story is really important, and then being able to expand, thinking about the flow and design. But story is the key element."

It's about planning

Sparks' last point about iteration speaks to something David Banner, managing director of Wales Interactive, is keen to underline: once the story is in place, the script needs to be iterated upon as well.

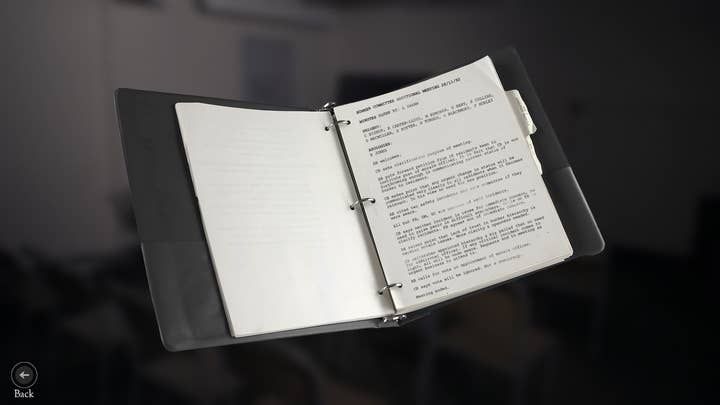

"We actually make them into choose-your-own-adventure interactive text scripts first," says Banner. "This enables us to play through at an early stage in text form so we can refine the script, as well as change things based on feedback and the budget before we go into pre-production."

Tim Cowles, director of The Shapeshifting Detective and The Infectious Madness of Doctor Dekker, adds: "Writing truly branching interactive fiction takes a lot of effort, especially as you'll always be thinking how much of it might end up on a particular playthrough's 'cutting room floor'.

Use choice effectively

Core to the appeal of interactive movie games is that 'interactive' bit. Players want to be able to make meaningful choices that genuinely influence the story.

Weber says a branched narrative must have "interesting and surprising consequences that manages to capture the audience's imagination and keep them engaged in the long run". He also advises against branches that lead to narrative dead ends - "They're frustrating and leave the audience with a shallow 'so what?' feeling."

Presentation of these choices is also crucial to engaging audiences. Past attempts at interactive movie games, particularly during the earlier FMV era, offered quite jarring experiences but the technology now exists to load videos more quickly for a smoother playthrough.

"Mostly they weren't seamless," Weber says of previous interactive movie games. "The user would watch a few minutes, then the movie would come to a stop at a decision point. This was down to technological limitations which have been overcome."

Think outside the box

With that in mind, it's worth considering how you can present your choices.

FlavourWorks co-founder and creative director Jack Attridge observes that "film and games are naturally incompatible in their current execution", adding: "Clicking hitboxes on top of a flat video will never feel meaningful on it's own."

There are plenty of examples of how to differentiate your title. Erica, the PS4 exclusive by Attridge's team uses special 'touch video' technology to enable players to interact with some of the live action elements, such as opening a drawer or turning a page.

CtrlMovie, meanwhile, has developed technology that allows multiple players -- even a cinema full of people -- to vote on each choice, with the majority dictating the next branch in the story.

Independent developer Sam Barlow won acclaim with his 2015 interactive movie game Her Story, which centred around police interviews where players had to actively search for keywords in order to uncover new footage.

More recently, Barlow's #WarGames -- a modern reimagining of the 1983 movie -- attempts something more unusual. Players' only agency is to select the character/video feed they want to focus on, but doing so actually dictates who progresses the story at certain, unannounced moments.

This helps solve another potential issue...

Players can be suspicious of choice

While interactive movie games are significantly different to traditional titles, they can still evoke that sense of 'winning' -- in most cases, getting the 'best' ending, or at least the ending the player hopes for or was most interested in.

However, Sparks notes: "With some of the games we've made in the past, if you give a choice of this or that, it feels to some people like that's a choice of right or wrong. And that puts people off -- it makes them feel like they're going to get it wrong at some point. From the small amount of research we've done, women in particular worry about this."

Hence the benefits of #WarGames' unconscious choice system, although Sparks warns that not signposting the moments choices are made can make players feel they have no impact on the story.

"Unconscious choice is better than conscious but then you don't feel like you have agency," he says. "How do you balance that? There are some people who think interactive storytelling should be about dictating where the story goes and you have power over where it goes. But then that's a massive conflict to the art form of storytelling."

Meanwhile, Weber warns: "Users are very suspicious of loops and irrelevant decisions. The storytelling has to remain consistent at all times, the audience must have a sense of agency and needs to feel they know what they're doing. Uninformed, random choosing is very frustrating. And last but not least the conclusions or endings have to be meaningful. So it's not easy to write a branched narrative that works on all these levels."

Draw on experience

Interactive movie games are ambitious projects and the live-action element is key to their broad appeal, making them accessible to audiences who may not be as comfortable with traditional video games.

However, games developers are not film-makers (and, indeed, vice versa) so anyone embarking on such a project must be willing to work with people far more experienced in that field.

"If you're doing live action, you absolutely need people with movie-making chops," says Sparks, although warns that "movie making is very expensive".

Banner adds: "It's important to collaborate with experienced film, writer, directors, producers and production companies. It's that cross-collaboration and pooling of resources, knowledge and abilities from the different industries which has been vital for creating our successful interactive live action projects."

Meanwhile, Weber reminds developers that there are plenty of game-makers who have already learned valuable lessons from their interactive movie games and built technology specifically for these projects.

"There is no need to reinvent any of that again," he says. "It's time to get out there and make some seriously consequential movies."

Budget appropriately

It seems obvious advice for any game, let alone interactive movie games. But the need to film live-action footage and potentially adopt different technology means it's important to ensure you are well-financed.

"You need a lot of money behind you, a hell of a lot, so you need to find people that really understand the risks of making hit-based stuff," says Sparks. "You need partners to take risks, and the ones who can take those risks are people like Sony. They've got the infrastructure to try and back you."

Cowles adds that developers should "budget not just in terms of money but the sheer amount of time required - especially for indie developers."

If you believe in it, go for it

Creating interactive movie games can seem a daunting endeavour, particularly given the need for experience few developers have, such as film-making. But Sparks remains optimistic, saying: "I don't think anyone should be put off by it... or think there's no future in it."

Cowles concludes: "Follow your heart. Forget about what you think will sell the most and just make the game you'd love to make. You'll have no regrets, and you'll find an audience who will appreciate it -- however big or small."