How stable are Dwarf Fortress' foundations?

15 years deep in development on the seminal fantasy simulation, Tarn Adams talks about the realities of fan-supported development

Dwarf Fortress is a remarkable game for a number of reasons, but one of the underappreciated ones is that the sibling dev team of Tarn and Zach Adams have released it as a free game and funded development largely through fan contributions on PayPal and Patreon.

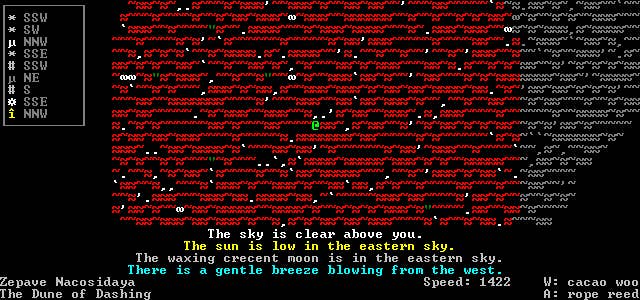

Conventional wisdom would suggest this is a precarious way to pursue a career, even for an industry notorious for precarity between its penchant for seasonal layoffs, fluctuating business models, and publisher implosions. Despite that, Dwarf Fortress has provided the pair with a sort of stability many developers would be thrilled to call their own. The first version of the game released to the public in 2006, and the brothers have treated it as a full-time job since 2007. Since then, it's been added to the MoMA collection, cited as an inspiration for Minecraft, and become the stuff of game development legend thanks to its absurdly complex simulation of a fantasy world rendered entirely in ASCII characters.

"There are certain tenuous aspects to this existence where two-thirds of your income may vanish overnight depending on how certain businesses operate"

But there are few certainties in gaming, even with that longevity and recognition. Speaking with GamesIndustry.biz at the Montreal International Games Summit last week, Tarn discussed the game's business model (for lack of a better term), and how recent proposed changes to Patreon fees provided a grim reminder of just how fleeting stability can be. Instead of passing variable processing fees onto creators receiving pledges, Patreon said it would begin tacking on a per-pledge charge of $0.35 plus 2.9% and making the pledgers cover it. That change drew plenty of backlash from creators and supporters alike, particularly for the way it discouraged people from backing a wide array of creators at very low amounts, a key behavior in the Patreon ecosystem. Patreon backtracked on the change late last week, but we spoke with Tarn in the midst of the incident, when numerous creators were reporting a wave of cancelled low-dollar pledges.

"As we're discovering, there are certain tenuous aspects to this existence where two-thirds of your income may vanish overnight depending on how certain businesses operate and whether they continue to exist," Adams said.

Adams clarified that Dwarf Fortress had only lost about $100 in pledges since the proposed fee change was announced days prior, "but it speaks to a larger issue, which is, do they understand their own model? If so, the messaging has been trash. I don't want to put too sharp a point on it because I may build ill will with my financial institution. But that's what I'm thinking of them as now: a financial institution, rather than a company that is creator-centered."

As his words imply, it wasn't always that way. Tarn said the company had been pleasant to work with up to this point. They sent out a nice plaque once Dwarf Fortress hit 1,000 backers and offered a tour of the offices, where Tarn said he picked up a "sort of legit vibe" from the people there. And while he wanted to wait for things to shake out before coming down too harshly on the company for one misstep, it's clear the move called into question much of the good will that had been built up. That's only prudent, as Patreon has become an unexpectedly vital part of Dwarf Fortress' ongoing success.

Before the Dwarf Fortress Patreon page went live in April of 2015, the Adams brothers primarily took contributions through PayPal. But once the Patreon was up, people by-and-large switched over, Tarn said. They used to receive about $3,000 a month through PayPal, with spikes upwards of $10,000 around major updates. These days it's closer to $1,000 a month from PayPal, and last month's major update drew a spike of only about $400.

For the most part, Dwarf Fortress has been better off with Patreon. As of this writing, Patreon draws more than $5,100 monthly from 1,822 supporters, so the loss of income spikes has been made up for by the overall increase in funding and predictability of when it arrives. But that predictability is undermined when one considers Patreon not as a creator-centered support mechanism but an arguably overvalued Silicon Valley start-up that has to figure out how to turn good will and popularity into a solid return on investment.

"For me, Patreon is the lion's share of the money coming in. If that disappeared overnight, that might also be Dwarf Fortress disappearing overnight, at least in terms of full-time work for a while"

"For me, Patreon is the lion's share of the money coming in," Tarn said. "If that disappeared overnight, that might also be Dwarf Fortress disappearing overnight, at least in terms of full-time work for a while. Because people aren't just going to migrate back to some other service. You actually genuinely lose those people unless they decide to re-up somewhere else."

The recent Patreon controversy is the sort of thing that happens when a company's desire to boost the bottom line conflicts with its desire to make customers happy. It's a delicate balance commercial game developers know well, and one that is not lost on Tarn, even if he's not a commercial game developer in the traditional sense.

"I'm not heavy on semantics," Tarn said. "I'm not too much different from what other people do. I still do press meetings. I still travel to events, and I still think about my image and all that kind of thing. I think about how the game's being steered and how I'm messaging that, but I'm not actually selling anything."

Subsisting on donations from strangers means Tarn will never have to justify a decision to a publisher or worry about securing retailer shelf space, but he's still answerable to other people holding the purse strings. As a result, he has to be thoughtful about how his community will react to everything he does. Having personally handled Dwarf Fortress' online forum since the beginning (he feels an obligation to keep moderator cliques, in-fighting, or buck-passing out of his community), Tarn feels he's learned a few things about community management.

"In terms of steering the boat slowly, I've generally not had any large conflagrations of fan revolts or that kind of thing," he said. "And you learn to do that, and you can also see where you might have screwed something up if you weren't being more careful. It's not like any of the outrageous harassment crap is valid, but just general ill feeling is often valid, and you can avoid this if you're careful oftentimes."

The possibility of upsetting supporters plays a factor in a number of decisions for Tarn. It's part of why he doesn't see himself changing gears to work on a different project in a new genre. Instead, he's more likely to work such interests out through side projects. Tarn says he and Zack used to churn games out several times a year before they started Dwarf Fortress (some are still available on the official website), and even though they still create side projects at nearly the same rate, they've been reluctant to actually release them.

"Just as a matter of practicality, I don't think I'll ever look at it and say 1.0 because we're not going to make it"

"The impact of releasing a game that's sort of crappy is unknown to me in terms of people being upset we spent time on it, or comparing it to Dwarf Fortress if we're actually trying to do something financial with it," Tarn said. "The easiest thing has been to not release them... [Dwarf Fortress supporters] don't begrudge me my time up to the minute. The main problem is once you put a side project out, there's a support obligation, then that's a much more public and possibly time-consuming process. And that could--not unexpectedly--ruffle some feathers."

Community reaction also played a part in the Adams' decision not to license out the Dwarf Fortress name to another developer making its own more commercial approximation of the brothers' title.

"The dollar amount just didn't make sense," Tarn said. "It wasn't bad, like three years of pay at our current level, but there's a chance you'd sour your fanbase if their product was particularly bad, or just in general. I mean, 'sellout' is such a ridiculous phrase, but there are perceptions. So we just had that in mind and said no, and the game came out without being called Dwarf Fortress."

So for now, that means there's only one true Dwarf Fortress, and the Adams will be working on it for the foreseeable future. It's been 15 years development started on the game, and the most recent release is 0.44.02. Tarn has a list of 2,600 features that serve as a target for a proper version 1.0, so the version number suggests the game's nearly halfway there, but nobody's planning any launch parties just yet.

"When people do the math, it's anywhere from 20 to 90 years to get through it, depending on how hard I've been working and how lucky I've been," Tarn said. "Just as a matter of practicality, I don't think I'll ever look at it and say 1.0 because we're not going to make it."

So what's the fate of Dwarf Fortress? Ultimately it looks like it will be given to the community that have supported Tarn and Zach throughout the game's development. When their work on the game is finished--whether they complete it to their satisfaction, find the financial rug pulled out from under them, or simply decide it's been long enough and put their tools down--the plan is to release the game's source code so others can build on the foundations of Dwarf Fortress however they wish.

"I've basically promised people it's going to be out there," Tarn said. "But no killing me, that's been stipulated. My brother will just throw it in the garbage fire and he'll be quite angry with you all."

Disclosure: MIGS has a media partnership with GamesIndustry.biz, and paid for our travel and accommodation during the event.