How does the games industry solve its problem with music licensing?

Developers risk having their games removed from sale due to expired licenses -- experts from music and games weigh in on the problem

Video games have been using licensed music in their soundtracks since the 80s. Midway's 1983 arcade game Journey featured 8-bit arrangements of the titular band's music, and the 1988 hip-hop track Megablast by Bomb the Bass was the title music for Xenon 2 Megablast on the Amiga.

As video game hardware evolved throughout the 80s and 90s, the technical limitations that had previously limited the use of music in games started to disappear, and the music industry saw a new opportunity. When CD quality audio became a reality, games like Road Rash, Tony Hawk's Pro Skater, FIFA and Wip3out demonstrated that video games could be a new format to market music and drive sales.

Today, the relationship between the two industries is mutually beneficial: developers can license popular music to make their games appeal to certain audiences, while musicians benefit from instantaneous exposure to millions of new listeners (and usually a lot of money). It's a healthy relationship, but like all relationships it isn't without problems -- and many of the problems associated with music licenses can cause some games to be removed from sale.

When developers want to feature music by bands and artists in their game, a licensing deal needs to be made. These deals can be very complicated due to a variety of reasons, from the length of the licensing agreement to future releases of video games affecting the original contract. Such issues have affected games such as Obsidian Entertainment's Alpha Protocol and Remedy's Alan Wake, both of which were removed from sale, although Alan Wake appeared back online after its music licenses were renegotiated.

What makes music licensing so complicated?

"Now that people are doing remasters and more and more games are starting to get re-released, we're starting to see issues"

"Licensing music for games can be a complicated business for three reasons," says Chris Cooke of CMU, who writes, talks, teaches and consults about the music industry. "First, the copyright in songs and the copyright in recordings are separate. So if you are using recordings of songs, you'll need to license two sets of rights -- the song rights and the recording rights.

"Second, copyrights can be co-owned and song copyrights routinely are. If you want to use a co-owned song you need to get permission separately from each co-owner, any one of which can say no.

"Third, if you sync a track into a game and then make that game available via an online network, in copyright terms you are both 'copying' and 'communicating' the music. This is important because, on the song's side, copying and communicating are often licensed separately. On top of all that, copyrights might be owned by different people or companies in different countries, and rules vary around the world."

That's a lot to take in, and most game developers aren't experts when it comes to the legalities around music licensing. If you want to feature licensed music in your video game, one of the easiest ways to protect yourself (and your game) is by working with music supervisors, who specialise in navigating the minefield.

"Most game companies employ music supervisors to handle their licensing," says Austin-based music lawyer Christian Castle, owner of Christian Castle Attorneys, a law firm specialising in music rights. "Electronic Arts is a great example. Game developers who are not at a major game publisher probably can't go down this route. Usually the developer wants to pay a flat fee for the sound recording and for the sync rights to the song.

"The most fundamental mistake we see is when developers miss that first step of separate clearances for the song and the recording. This mistake usually only has to happen once and they [developers] learn the hard way. It's an old problem."

How has video game music licensing changed?

Randy Eckhardt, founder of Eckhardt Consulting, has a career spanning 25 years in the games industry. He first started working with record labels at EA for the release of Road Rash in 1995, which featured music by the popular rock act Soundgarden. As both industries were undergoing rapid growth, the arrangements around licensing music for video games were a work in progress. A lot has changed since.

"[Back then] The industries couldn't be further apart," Eckhardt explains. "The recording business was in a heyday with grunge [rock], the commercialization of hip-hop, pop-punk and so on. The games industry, however, was still in the early stages of establishing itself.

"Fast-forward 25 years and you've got billions of dollars in sales for music-inspired games, and massive soundtracks with games like Grand Theft Auto with $50 million to $200 million development budgets. Then there's movie franchise game releases, game franchises becoming movies, and broadcast streaming and viewing of games taking the young generation by storm."

As the industry has continued to grow and the shelf life of video games has grown as a result, there's been a more concentrated effort from developers and publishers to get music licenses granted in perpetuity -- but this can be costly. Justin Andree, senior music supervisor at Cord Worldwide, believes that the issues affecting games such as Alan Wake and Alpha Protocol are more common than people realise, and will affect more games in the future.

"In the past three or so years we've had more publishers agreeing perpetuity licenses to avoid issues like these"

"Now that people are doing remasters and more and more games are starting to get re-released, we're starting to see issues," he explains. "In the past three or so years we've had more publishers agreeing perpetuity licenses to avoid issues like these in the future."

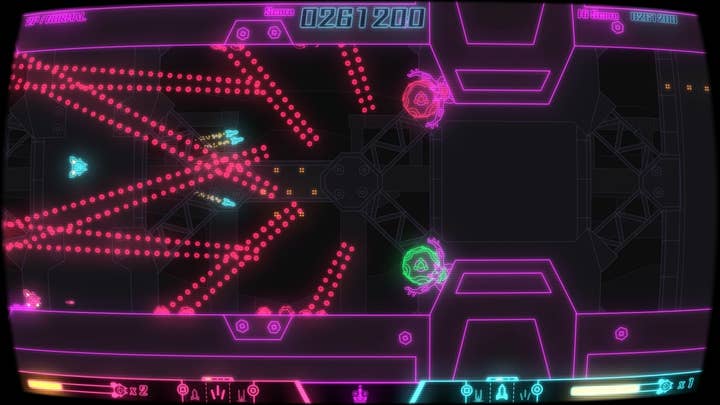

Q-Games' Pixeljunk Sidescroller was released for the PlayStation 3 in October 2011, but it had to be removed from sale when the music licensing contract between Sony and the artist whose music featured in the game, Alex Paterson, expired. It highlights a common issue affecting games were the music has only been licensed for a set number of a years.

"We were told the game was going to be removed about a month or two before the expiry," Dylan Cuthbert, founder of Q-Games, explains. "It is the first and only time this has happened to us for any game we have ever made."

When music licenses in a video game expire that game must be removed from sale until a new licensing deal is agreed. Such an opportunity wasn't presented to Cuthbert, whose reaction to the game's removal was, "disappointment and disbelief... Negotiating the rights in the first place was a more difficult and prolonged experience than I had experienced before."

When renegotiations do take place due to expired music licenses, Randy Eckhardt believes that it should never be too difficult for the two industries to work together amicably and find a solution.

"To be fair, the labels typically work in good faith to get those rights extended, and don't look to take unnecessary financial advantages because they know we're all in it together for the long run," he explains. "Moreover, there are times when an initial license, depending on who your music consultant is/was, can cover 'future or now unknown platforms.' This generally is a good faith gesture and eliminates the need to go back to the record label and music publisher for extended terms/uses on new platforms."

The power of negotiation

There are many variables to consider when labels enter negotiations with game developers and music supervisors. Music supervisors at EA will work up to a year in advance with music labels so they're aware of album schedules and new music releases. Music managers and record labels will have to determine the value of the artists that feature in those games.

Ariel Gross, founder of Team Audio and Audio Mentoring, has over 20 years' experience in game audio and says the cost of licensing music for a video game can vary from anywhere between a two-digit to a six-digit figure. When he was working in the audio department on Saints Row, the cost of licensing the music for the second game in the series cost close to $1 million.

"If you want to use music that's written by someone like Kanye West you can easily spend between $100,000 to $200,000 on a single track," Gross explains. "Sometimes labels are willing to lower rates if you choose a selection of tracks, or choose to feature music from an artist that might be up and coming. Games like FIFA and Grand Theft Auto are trend-setters for music. If you're an upcoming artist and you can get your music featured in games like these it can launch your career."

"More and more game companies are forming distribution channels and a lot of soundtracks are being pressed to vinyl"

"People are a lot more sophisticated now on both sides," music lawyer Christian Castle agrees. "Publishers avoid royalty deals like the plague, and that of course drives up the up-front cash payments."

Finding flexibility in costs

Thankfully, there are ways to keep costs down if you want to feature licensed music in your game and have a small team. One of the easiest ways is using library music that has been written for commercial use. There are also many pieces of music in the public domain due to copyright expiring, which means a licensing fee does not need to be paid.

If developers are adamant they want a certain piece of music to feature in a game but simply cannot afford it, they may consider a 'soundalike' -- a recording of a song that has been created to closely resemble another track.

"The classic soundalike is when a potential user or licensee approaches the owner of either or both these rights and gets a price they don't like," music lawyer Christian castle explains. "The user then creates what is essentially at least a competitive and possibly an unauthorized derivative work.

"That paper trail potentially shows intentional infringement, and possibly other things like misappropriation of someone's right of publicity (usually the featured artists) or unfair trade practices. Many of these cases arise in advertising. If the new work is 'inspired by' it's going to depend a lot on the extent of inspiration, such as the Blurred Lines case."

The case Christian is referring to ended in a $5 million judgement against musicians Robin Thicke and Pharrel Williams for copyright infringement, due to similarities between their song Blurred Lines and Marvin Gaye's Got To Give it Up. Because of the legal complexities surrounding them, developers should always enlist the support of a respected legal team if they are considering the use of soundalikes in a game.

"If you're considering a soundalike, it's incredibly important to get the support of a decent lawyer who can prove that both tracks are legally distinct," Ariel Gross explains. "It's all very grey."

Of course, there's nothing stopping developers from directly approaching unsigned bands and artists to see if they're interested in composing music for their game. Capy Games approached one of the team's favourite composers, indie-folk musician Jim Guthrie, to compose the music for their Superbrothers: Sword and Sworcery EP. The game has sold over a million copies, benefiting both the developers of the game and the composer, whose music was discovered by its players. As the lines between the music and game industries become blurred, we can expect to see more bands like 65daysofstatic (No Man's Sky), Daughter (Life is Strange: Before the Storm) and HEALTH (Max Payne 3) writing music for video games.

"The best thing that bands can do right now is recognise the market and learn how to compose music for interactive games, which is a very different experience to how you'd usually approach music composition," Ariel Gross explains. "More and more video game companies are forming distribution channels and a lot of soundtracks are being pressed to vinyl. That's only going to continue."

Avoiding the pitfalls associated with licensed music

"Ambitions to streamline music licensing has been on everyone's wish list across all entertainment industries for decades"

Despite the potential legal ramifications of featuring licensed music in video games, it's easy to protect yourself by working with professionals who specialise in music licensing, and ensuring you're aware of and have read any contracts detailing the use of music in your game.

"You have to read the contract carefully," says Christian Castle. "If you have a lot of licensed cues, someone should create a music rights bible that allows you to track your rights. Also, it's a good idea to have one set of terms apply to all songs and all recordings. If there is a composer, the score should be either owned by the developer or licensed in perpetuity. If you are actually manufacturing or authorizing a game publisher to manufacture, you have to be especially careful so you don't have product on the warehouse floor that is locked down because of a music rights clearance.

"Developers need to have a clear understanding of the rights they need and do what they can to get perpetual buyouts in all platforms. This may require a bigger budget than you think. Get an experienced music supervisor to help you if your needs become complex."

Castle advises that bands interested in having their music featured in video games should be flexible to such requests, especially if they own all the rights.

"If they want their label to cooperate, the manager needs to hand walk that request through the label and then the publishers."

Streamlining the music licensing process

Randy Eckhardt believes that while there are many who wish the processes around licensing music could be streamlined, it will always be time-consuming.

"Ambitions to streamline music licensing has been on everyone's wish list across all entertainment industries for decades," he explains. "With master recording and copyright/publishing rights constantly changing between artists, songwriters and content -- along with an ongoing array of new types of 'use' requests -- it will still be an iterative, somewhat time-consuming process that should include expert folks driving the efforts as the most effective streamlined method."

Chris Cooke agrees that while streamlining the process will take time, one potential way to solve the issue in the future would be a central database of copyright ownership.

"Something that would help a lot would be a central database of copyright ownership, that could tell licensees who controls what music in what countries, and maybe even whether they are up for licensing music to different media and, if so, on what terms," Cooke explains. "Because in most countries there is no formal copyright registration -- that central database doesn't exist. The aforementioned collecting societies have databases, but they aren't necessarily complete or publicly available, and different databases don't necessarily agree.

"There has been much debate in the music industry as to how music rights data could be better managed and distributed, and various rights owners, societies and start-ups have proposed solutions, some employing the blockchain in some way. Projects like this move slowly, but I think there will be some progress in the years ahead, not least because bad data is stopping artists and songwriters from getting paid."