Have M-rated games grown their market share? | 10 Years Ago This Month

A decade after publishers bet on fewer, bigger, bloodier titles, does the industry depend on violent games like it used to?

The games industry moves pretty fast, and there's a tendency for all involved to look constantly to what's next without so much worrying about what came before. That said, even an industry so entrenched in the now can learn from its past. So to refresh our collective memory and perhaps offer some perspective on our field's history, GamesIndustry.biz runs this monthly feature highlighting happenings in gaming from exactly a decade ago.

If it seems like just yesterday we ran our monthly retrospective column, well, it was.

But May of 2013 played host to the Xbox One reveal event, a debacle that consumed the column entirely on its own, leaving little room for other subjects like the seemingly evergreen one we're going to talk about today: violence.

A decade ago, I wrote an editorial on the game industry's then-increasing reliance on violent games.

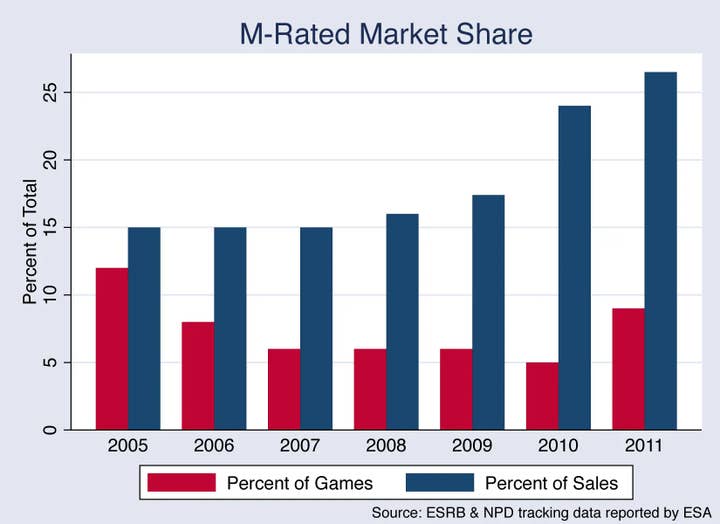

The key evidence was that M-rated games had been declining as a percentage of games released each year, but significantly growing the amount of industry revenues they represented. In 2011, only about 9% of games had an M-rating, but they collectively represented almost 27% of revenues in the US.

The Entertainment Software Association stopped reporting on each rating's market share after the 2011 figures were put out, likely because it was unclear just how much higher that M-rated market share could go. The industry was still a popular scapegoat among many politicians, and even a Supreme Court decision affirming free speech protections for games wouldn't stop them from being used as a cynical distraction from gun control.

So when I saw that editorial in putting together this month's 10 Years Ago column, I got curious about how those numbers would look today.

M-rated franchises like Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto are even bigger now than they were a decade and change ago, while Mortal Kombat, Assassin's Creed, Resident Evil, and God of War have all seen their most successful entries released in recent years.

But the opposite side of the ratings spectrum is also considerably stronger now than it was in 2011, thanks in part to Nintendo's relative weakness then and strength today.

The Wii phenomenon had all but collapsed by 2011, and the 3DS didn't start to turn the corner from its disastrous launch until the last two months of the year with the debuts of Mario Kart 7 and Super Mario 3D Land.

Compare that to recent years which have seen the Switch thrive alongside megahits like Fortnite (rated T) and Minecraft (E10+).

Add in the effect of the pandemic significantly growing the market by bringing in both lapsed and new players, and I could have seen that M-rated market share going either way.

Fortunately, the number crunchers at Circana (formerly NPD, which compiled the original market share figures for the ESA) were willing to indulge my curiosity, with a few caveats. They gave me the M-rating market share for physical sales of the past five years, because Nintendo doesn't report its digital sales to the company and the absence of Switch first-party titles would significantly skew the results.

Beyond that, they noted that the exclusion of downloadable content, microtransactions, and subscription spending from the equation means these modern numbers are nowhere near as comprehensive a look at the console and PC market as the ones from a dozen years ago that we're comparing them to.

That said, it's more information than we had before, so many thanks to Circana.

And in case you were wondering whether the market share of M-rated titles had gotten higher or lower since 2011, the answer is "both."

- 2018 - 35.1%

- 2019 - 30.1%

- 2020 - 26.2%

- 2021 - 20.6%

- 2022 - 22.1%

That 2018 figure is kind of dire, right? That was a little bit of an outlier year with M-rated games as the top two best-sellers (Red Dead Redemption 2 and Call of Duty: Black Ops 4) and only one Switch game in the top ten (Super Smash Bros Ultimate at No.5).

I suspect the Switch and the pandemic alike drove the declines since 2020 as a broader audience of people re-discovered consoles or gave them a shot in the first place, though it seems both of those effects may be wearing off.

Back then I was worried about the medium marginalizing itself... but the world of games feels far bigger these days

And while the lack of Switch first-party sales in the digital data would almost certainly skew those numbers toward a greater percentage of M-rated titles, so would the fact that the broader Switch customer base has not adopted digital distribution as heavily as others.

Nintendo reported almost 48% of software sales coming from physical game sales last year, a far cry from the publishers of games like Far Cry.

Digital sales made up 85% of Ubisoft's business last year. For EA, that figure is 90%. For Take-Two, digital accounted for 95% of revenues. For Activision Blizzard, it was 96%. Some of those numbers are skewed by overwhelmingly digital divisions like Blizzard, King, and Zynga, but the digitial/physical mix on Nintendo games is absolutely an outlier in the industry.

The overall M-rated market share on consoles and PC might be truly ugly when you factor in the digital numbers, but even if it surpasses the 2018 high of 35.1%, I would find it hard to muster the same concern as I did a decade ago.

Back then I was worried about the medium marginalizing itself by leaning too heavily into the gratuitous violence that was so often used as a sales hook in the AAA world.

But the medium of games outside AAA is so much bigger these days. It's not just that we have a seemingly unlimited number of indie and mobile games offering different visions of what games can be; it's that so many of them are successful enough to not only merit mainstream attention alongside the AAA world, but to have their alternative approaches to everything then feed back into AAA and influence what we see from there.

The industry has thrived and diversified over the past decade, producing megahits for a wide range of platforms, audiences, and monetization models. The Last of Us is not Candy Crush is not League of Legends is not Genshin Impact is not Minecraft is not Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom.

The M-rated end of the AAA console and PC space is less the face of the games industry these days and more just another face in the crowd. And that's ultimately a win for all involved.