Going in Blind to VR development

Tiny Bull's Matteo Lana describes the years-long struggle of developing VR exploration game Blind in Italy's emerging development scene

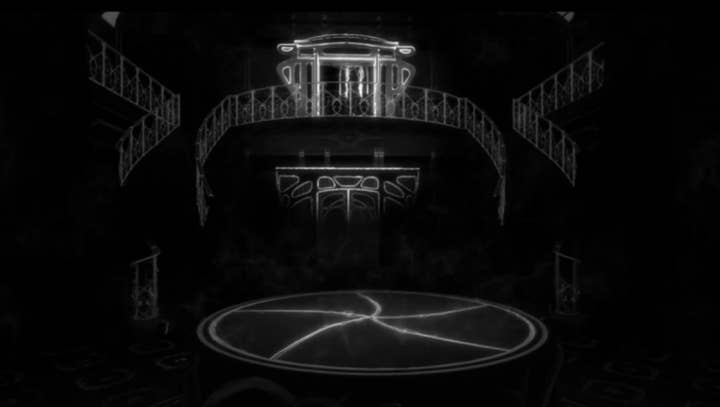

Small studios developing their first games have struggles aplenty even when working with established platforms and genres in countries with thriving industries. But Tiny Bull Studios, headed up by Matteo Lana, took on an even greater challenge developing VR game Blind in a country where the industry is still fighting for widespread acceptance.

Tiny Bull is based in Turin, Italy, and was founded by Lana and his former classmate at the University of Turin, Rocco Luigi Tartaglia. The two started working together doing freelance B2B work to gain experience and raise money ahead of the studio's official founding in 2013. Work on Blind began a year later.

But when Blind started development, the B2B projects didn't fully go away. Lana told me the studio constantly had to balance freelance work with its passion project. That, he said, was one of the reasons Blind took four years to develop. And during that time, the studio struggled further as its members came and went.

"We saw many, many other Italians going away to work in game development but thought, 'Why not try and build something here at home?'"

"Many people who collaborated with us over the years at some point got scared or found a job that was paying better money and decided to go away," Lana said. "Even people who started working with us and were passionate about the project. Since development was taking so long and we were always low on funds, they eventually decided to leave and start doing something else."

The challenge was further amplified by the studio's location in a country where budding game studios have had an uphill battle to get support.

"We were born here and we love the city," said Lana. "A lot of people tend to move away from Italy to try and work in game development, but we didn't really feel like going away. We wanted to try and help the industry grow here in Italy. Back when we started, it was pretty much non-existent. We saw many, many other Italians going away to work in game development but thought, 'Why not try and build something here at home?'"

Lana's attachment to his home is reflected in the name of his studio - Turin is Italian for "little bull." The trouble with staying in the city he loves, Lana said, doesn't have to do with Italy's economy on the whole, but rather with a specific perception of video games and those who make them both from the government and community at large. Lana believes Tiny Bull could have developed Blind faster, without as much reliance on freelance work, if the government supported game development as much as it has other industries.

"Most people [in Italy] think we game developers are just grown kids that still like to play games"

"Italy has a history of different kinds of industries," he said. "Automotive has always been very strong, and there's fashion and food, but gaming and software development in general have never been seen as actual jobs. For a long time, and even now probably, most people think we game developers are just grown kids that still like to play games and they think we play games all day or something. The game industry in Italy still isn't taken seriously by a lot of people, even though Italy is a pretty big market for games.

"It's silly that the industry hasn't grown as much as in other countries. That's probably why a lot of people were leaving up to 10, five years ago, even now probably. If you don't want to start a new company, you have to go somewhere else because there are like three big studios in Italy, and it's not that easy to be hired by them. Many people find it easier to just go somewhere else."

But Lana hopes the risk of staying in Turin to start a studio will pay off soon, and he's seen reason for optimism. Lana said that in the last 10 years, Italy has begun to see a shift in perception of game development as a legitimate industry, and multiple indie startups have begun, grown, and succeeded both in the country as a whole and in Turin. Tiny Bull, for example, has worked with a number of multicultural developers from places such as Argentina, France, and Egypt, though Lana said in general people do not come to Italy to start studios or find work in the industry.

He also cited Ubisoft Milan's Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle as an example of a major money-making release that helped change the perception, and credited groups like the AESVI (Italian Entertainment Software Publishers Association) with strides in getting the industry more recognition.

"Even now AESVI is fighting to help us developers get some tax breaks and stuff like that," he said. "We know that games are a form of art and a way of expressing something just like cinema, but here in Italy only filmmakers get to enjoy tax breaks, tax credits, tax shelters, things like that. And finally after years of fighting things are starting to change for us as well."

"When someone asks, 'Should I go through with making a VR game?' the answer is almost always, 'No.'"

The struggles of Italy's gaming industry are not the only ones Blind had to face. Blind is a VR-exclusive game - a riskier development prospect in a location with fewer support networks. Lana said that he and Tiny Bull knew they would have an uphill battle going in, though the initial decision to develop in the medium was partially an accident.

"We were fully aware of the risk [of developing in VR] and it was on us. At the beginning when we pitched the game to [publisher] Fellow Traveler, the concept was for just a game based on echolocation and a blind girl. VR wasn't in the picture. But when we pitched it, they said, 'It's a cool concept, so you're making this for VR, right?' And we were like, '....Sure, yes, of course. Do you think we're stupid or something?' And that's kind of how VR got into the picture."

"Back then it felt like an interesting challenge and we thought it would be interesting to work around an emerging technology. Everyone was talking about VR, so we thought 'Why not? Let's give it a try.' Now, of course, looking back, we might have been a bit reckless, especially considering we didn't have a lot of experience in these kinds of games."

Lana said he would not necessarily recommend Tiny Bull's choices to other studios looking to get started.

"We are in a lot of developer groups and chats and forums and whatnot and the big question is always, 'How do we make this work? How can we create something that will sell enough to allow us to make another game?'" Lana said. "There's a lot of discussing the market and strategies, and when someone asks, 'Should I go through with making a VR game?' the answer is almost always, 'No. It's not worth the risk. There aren't enough players around and if your game is less than perfect, no one will like it and you'll fail horribly.' It's all very pragmatic."

Lana applied that same pragmatism to Blind. When we spoke four days before the game's launch, he still wasn't confident it would be a success. Still, just seeing the project through to release is an accomplishment, one Lana attributed to perseverance and a good publisher.

"What we feel VR is best for is the weird stuff. That's where it finds its true potential"

"We felt we were very lucky to meet Fellow Traveler and sign with them," said Lana. "They've been such a great help over the years, especially when things got difficult, like when we had doubts or when other games with similar premises were announced. They helped us get through it and make the best of it. We could have never released a game on our own. If not for them, Blind would never have seen the light of day."

Though Lana personally would not recommend Tiny Bull's journey to other budding studios, he is optimistic about VR on the whole, and is glad to have contributed to furthering the medium both in Italy and globally.

"We never regretted our decision. We are happy that we actually chose to go through with a VR-only game. We think VR has a lot to offer, and still has a lot of growing to do. It's still a niche market. It's always a risk to do something like that. But we're confident that eventually enough players are going to start playing VR alongside other traditional games. Growth has been stable over the years. Just now PSVR passed 3 million devices worldwide, and that's encouraging.

"We think VR is great because it allows developers to create incredible worlds and incredible visions. It's immersive, it's super interesting what you can do with it. What we feel VR is best for is the weird stuff. That's where it finds its true potential, because you can do so many things in VR that are not possible with normal, traditional games. Every time we see a weird concept, we're happy."