Gaming vets dish out career advice

Confused about how to get into the industry or climb the ladder? Trip Hawkins, Warren Spector, Ed Fries and more offer tips

After kicking off our "Feature Focus" this month on game industry careers by picking the brains of top recruiters in the business, we decided to bring you the wisdom of people who've been leading teams and making games for a number of years. Some of these veterans have been in the industry for well over two decades, but regardless of their time spent in gaming, each has had to make tough decisions to determine the career path that's right for them.

There's no "magic bullet" to gain entrance into the video game business if you don't have the talent, the drive and the dedication to your craft, but hopefully the advice from GamesIndustry International's panel can assist you in some small way.

Trip Hawkins, founder of EA, Digital Chocolate, If You Can

I think there are two really important things. The first one is be willing to start out working for free, because it's very easy to get in the door someplace if you have a real value-add in terms of your skills and what you can do. And the price is right if it's free - it's hard to say no. That's basically how I started in my career, so I'm a really big believer in that. Frankly, if you're getting in line with everybody else expecting to be paid, it's a long line.

One of the mistakes I think a lot of people make is that they haven't thought very much about their education, and by the time they decide they want to get into the industry they haven't built the right academic background or skill set. For anyone who's thinking about games as a profession, there are so many ways you can craft your college experience to better support that, and certainly studying engineering or computer science would be at the top of the list, or becoming a really capable artist who has mastery of all the state of the art tools. And honestly, even just being a good mathematician or statistician now is [very useful], with the whole category of business intelligence and metrics being really important growing categories in the industry.

For people who are more on the soft science end or humanities end, it's tougher to get in, if say, you're studying creative writing and you're thinking you're going to come in and write a game story. Also, people might delay when they get work experience because they're not figuring out where they want to be or how to kick the door down and make themselves look attractive.

There are some people who go in through testing, but so many people play games and that doesn't differentiate you from everybody else. Those people think they can just get in the door if they apply to be a contract tester, but it's a very fungible role and the companies that are paying the testers don't care about them very much and they don't consider it a great place to plant and grow people. So it's pretty difficult to migrate out of testing and into the offices as a [regular] employee. It does happen occasionally, and I think if somebody was to go on that route the best way to do it would be to demonstrate a high emotional intelligence in the testing function so that you don't get frustrated and you demonstrate a capacity to work smoothly with production teams and to not get rattled.

Generally, testing also deals with customer service, so if you're able to deal with customers that are complaining and you don't lose your cool that's a way of demonstrating that you have some management capacity and maybe then become a supervisor and then a manager in testing or in customer service. That starts to get you a level of visibility and credibility as a professional that would then make it easier to make the contacts you would need to maybe move into a different function. And when you get an opportunity in an organization, be really observant. I was at Apple, I was in the room with the founders, and I was extremely observant. I left there and started EA and didn't do that bad.

Warren Spector, Director of the Denius-Sams Gaming Academy at The University of Texas at Austin (now taking applications)

For starters, make sure you're truly passionate about making games. It's grindingly hard work and if you don't love it, it'll wear you down in a hurry. On a related note, make sure you're prepared for the transition from game PLAYER to game MAKER. As you get deeper into development you'll find your playing time going down and your making time going up. I can all but guarantee you'll end up playing far fewer games than you used to - a risk any time you turn a hobby into a career.

Don't assume that loving games is enough. If all you've experienced of life is games, the best you can hope to achieve is games that imitate other games. We're too young a medium for that. We need people whose life experience is as varied and as rich as our desired audience. You can get that experience in the workplace (even outside of games) or in school, but get it. Read books, watch movies, study things that don't seem to have anything to do with games. It'll stand you in good stead.

And speaking of schools, it's amazing to me that you can now study game development at hundreds of colleges and universities around the world. If you had told me even ten years ago that that would be the case I would have said you were nuts. A game degree can be a plus but make sure the program you attend gives you hands-on experience of development in a team setting. (This isn't a high hurdle, since most programs understand and meet this need...)

In school (or out) figure out what you want to specialize in. Unless you're going the indie route (a realistic option nowadays - finally!), generalists are tough hires. The industry is moving more and more (and more) toward specialists. Be the best in your field. The competition for open slots is fierce. And, just to hammer home the life-experience point, once you're on the road to greatness in your specialty, learn at least a little about each of the other disciplines associated with game development - if you're a programmer, learn something of game art and design; if you're a designer, learn some programming and art; if you're an artist, learn some coding and design. You get the idea. Finally, don't neglect topics that seem unrelated to games. Study some economics... some psychology... some history... One of the great joys of being in the game business is that our content is diverse enough you never know what you'll need to know!

All this high level stuff is all well and good, but what about specifics? If you want a job as a programmer, artist, designer, audio specialist or anything else game-related, make sure you have a solid portfolio of relevant work. Identify studios that make the kinds of games you love and be dogged in your pursuit of work there. (Working on games you don't love may be necessary but it can also be soul-crushing. Try to avoid it.) If you can't break in in your specialty (especially true of those who aspire to production and design jobs, I think), consider a stint in QA. You'll get the chance to interact with team members and show them your sense of what makes a great game. Once you're in, team interaction can keep you there.

That's an overview of what I'd do if I were starting out today UNLESS I had a game concept I burned to make. In that case, I'd seriously consider an indie effort. The amazing thing about the game business today is that anyone with some skills and a game concept can execute against that concept and reach an audience with a finished game. That's astonishing - another situation where ten years ago I would have said "no way." The indie scene is increasingly relevant and important to our future. And a small team - even a team of one - can make and distribute a game.

So, one final note that stems from all of this: Make games. Don't wait to get a job. Start making games today. Stop reading. Go do it.

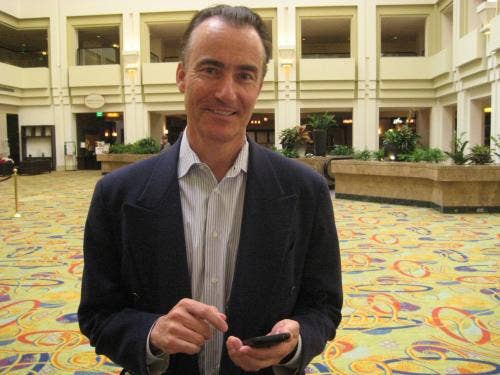

Ed Fries, co-creator of original Xbox

I think it's an easy question that everyone should answer the same way: they should make stuff. Whatever it is they do, whether they're a musician, artist, writer, programmer, there's no excuse. All the tools are there to make stuff. That's how we all got into it in the old days. We made stuff, not because it was our job, but because we had a passion for it. And then people noticed the stuff that we made. If you don't make stuff, then no one will notice.

And that's also how you learn - you'll learn what works and what doesn't and how you'll differentiate yourself from other people. In industry interviews, all the time when people are asked to describe a project they worked on, they're like, "Oh for school I had this assignment to make this game..." but I don't want to hear about that. I want to hear about what you made for fun! Because you care about it.

The best career advice I got came at a time when I was trying to decide between several different career choices, and it was a very stressful time for me. And even though I was relatively low in the company my office happened to have been for a couple years next door to the president of the company. It was a guy named Mike Maples, who was a very non-Microsoft guy... he was southern and he would just kind of sit back and when he'd say something in his southern drawl, everybody would turn and be like "oh..." I asked him for advice one day, and he said, "Ed, sometimes you don't have all the information you need. Sometimes you just gotta decide." And at first, it didn't sound that deep, but what he's saying is that the world's unpredictable and we have to make decisions and then deal with what happens along the way and then make more decisions. You can get paralyzed trying to figure out every possible [scenario] and ever since then I've seen that in many, many meetings and situations where people are trying to figure out so much stuff about what might happen.

Keiji Inafune, former Capcom exec, founder of Comcept (working on Mighty No. 9)

It's different from how it used to be in the past. There are a lot of big publishers today, big titles, but one of the problems with a lot of people trying to get into the industry is they'll often want to get into the industry because of these big titles and big publishers. They'll say, "I want to make Monster Hunter. I want to make Resident Evil. I want to make Mega Man." But if somebody came and did an interview at Comcept, what I would want to hear is, "I want to make my game. I want to make something better than these games. What I want to make is going to be the best." Have confidence in something new; don't just want to make what already exists.

When I first got into the game industry, there were really few large titles, especially at Capcom. Probably the biggest title that was there at the time was Ghosts n' Goblins. It was a pretty big game at the time, but it wasn't anything like the huge games we have today. I feel I was lucky to be in that situation where I had the chance to come up with completely new things, and I want other people who are coming into game development from here on out to be able to think that way as well, to believe they are lucky if they don't get to work on any big games.

Robin Hunicke, founder of Funomena

I always say to people that the thing I did was I looked at the games I loved, tried to figure out who worked on those games, and I would reach out to those people and have a genuine conversation with them about how much I love their work. And I would ask them, "If you were me, and you wanted to be working on a game like yours, what should I do? What kinds of things do you look for in a person?" Just have that conversation respectfully, genuinely. It's not networking. It's literally being curious about the things you love.

There's a huge difference between going to a conference, handing out your card, giving someone your demo, talking, talking, talking and going to someone and saying, "I really love what you did with Heavy Rain. I have a really interesting question I want to ask you. Would you take 10 minutes to discuss with me the design decision you made at this point in the game? Because I didn't understand it, but I love the game and I want to know why you did that."

I've done that. I went to David Cage and did this long after I was in the industry. I still go to developers whose work I love and respect, whose work moved me, and I ask them, "Dude, what was up with that?" It means you're engaged and learning from the people you want to work with, and that approach drives your thinking and the way you see things into what I see as the core skill of anyone that works in games: that curiosity and problem solving, the willingness to approach the problem from a different perspective. That's what games are about.

Andrew Sheppard, president of Kabam Studios

The industry is changing so much. The best advice I could give is to be true to what you really want for the long-term. If you want to be a part free-to-play, if you want to be a part of the mobile market, and you understand that the business model is changing and that a lot of growth in the industry, but also career-wise, exists in that dimension, then I'd encourage people out of school to go in that direction. But you have to be passionate about that type of gameplay. And if you're not passionate about that, if you want to build AAA games, then go do that. Don't just hop on the bandwagon. If you're true to what you want to do, what you believe will make you happy for the long-term, then you'll have passion and you'll have conviction, and if you maintain humility you'll be successful. More often than not, it's about putting yourself where you'll be the most happy and be the most passionate and everything flows.

I was at a women's networking event with my then girlfriend at the time, and a partner from the Mayfield Fund, Janice Roberts, was talking about her career and she said, "The one thing I realized I always did subconsciously was to skate to where the growth was and to be there first." And I took that to heart and that was part of the reason why I left traditional gaming to go to free-to-play gaming. I believed in it because I was looking at it from a strategy perspective for years and I knew that what was happening in Asia was ahead of its time and so I jumped into free-to-play six years ago. I remember former [colleagues] at traditional game companies saying, "That's never going to work, you're going to fail." But I had the conviction to go and grind, and it was hard, but just by grinding I learned so much. I wouldn't be able to do the job I'm doing now if I hadn't taken that leap of faith. So it applies not just to business models and market growth, but it applies to creative direction and political movements... but go where you believe the market is going and where consumers are going and if you get there first and you work hard and you listen and then you could be a part of something big. And if you're wrong, you better change fast. You won't come out with money, but you'll definitely come out with knowledge!

Brendan Sinclair also contributed to this article