"Games tend to be marketed by numbers, story is hard to quantify"

King of Dragon Pass creator David Dunham talks to Jurie Horneman about the importance of a solid narrative framework

King of Dragon Pass is a story-based strategy/simulation game, set in the fantasy world of Glorantha. Original released in 1999, re-released on iOS in 2011, it is still regularly discussed, and I often run into fans (last time, memorably, in a sauna in Finland). I wanted to know how this unique blend of genres, game mechanics and story elements got made, so I asked David Dunham, the creator of the game.

What do you think of the reputation and influence of King of Dragon Pass? Why do you think people remember it, whereas many other games from 1999 have long been forgotten?

David Dunham: Well, obviously I'd like to think that it's because it's a good game. It is definitely a distinctive game - I'm not aware of anything that's really anything like it (although it has influenced games such as Banner Saga and Fallen London).

The game is all about game play, and not dependent on specific technology. It doesn't have low quality polygons and textures. So there's no "gee whiz" that was supplanted the next year by "next generation" graphics. And our art and music weren't otherwise limited by technology, either.

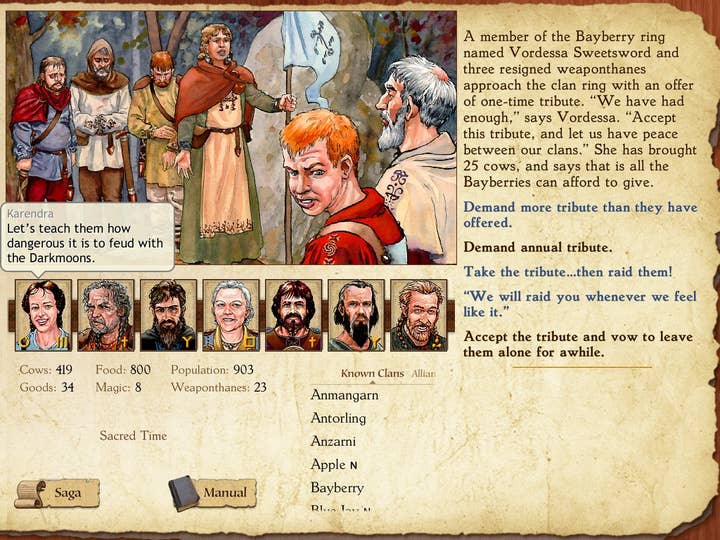

It's a storytelling game, with a strong mythology. These are fundamental parts of human psychology, but tend to be weak in most games. So we stood out.

It's also a really big game. We tried to allow for 40 hours of play, with no two games quite the same. So you can get a subtly different story each time you go back to the game.

"It's a storytelling game, with a strong mythology. These are fundamental parts of human psychology, but tend to be weak in most games. So we stood out"

The influence might have been greater if the game had been more well known. It certainly seems to be mentioned a lot more now that it's back in distribution.

How do you see the evolution of the market for King of Dragon Pass, from when it was released, to when the iOS version was released in 2011?

David Dunham: We released King of Dragon Pass in 1999, and quickly learned that in the US, the distribution channels made a lot of their money by selling shelf space or ads targeted at stores, not by selling the game. This wasn't a game that indies could really participate in. Luckily our license helped us also sell through hobby game stores, which were more focused on selling products. This was one of the reasons we did so well in Finland. We also sold online, but it was before the days of downloadable software. It was also still the era of boxes full of air - we had to ship and warehouse a fairly big box to hold the CD and manual. Given how things turned out, we probably should have gone with a DVD case, but it was too new and unusual back then.

Since distribution was originally such a problem for us, the iOS App Store was a big step forward. Pretty much anyone could be there, and your website could link directly to the game (unlike other mobile stores at the time). And while discovery was a problem even by 2011, we had the advantage of that fond remembrance you mentioned.

As an aside, at the time we were working on King of Dragon Pass for iPhone, the download would have been too large for the Android store. Google eventually allowed large apps, so the market has gotten better in that regard.

On the downside, we've seen the race to the bottom in terms of price. We picked a high-for-the-App-Store price, which in retrospect seems like the right decision. It was actually a big part of our indie marketing strategy: it signals a quality product that won't nag you or show annoying ads.

I think there continues to be a market for "premium" or "pay-once" games. It may be a niche, but it's one that an indie can fill. We want to make a great game first and then figure out how to sell it, rather than figure out selling and try to make a game around that.

King of Dragon Pass is set in the fictional world of Glorantha, created by Greg Stafford. It's a world with a long history, in both senses of the word, and the recent Guide to Glorantha Kickstarter showed it still has a strong fanbase. But it's not well known in computer game circles. On the one hand, King of Dragon Pass had a pre-built audience, on the other hand, it's a setting that can appear arcane and daunting to newcomers. How did you deal with that, and how have your feelings about this evolved over time?

David Dunham: Right, Glorantha is probably still best known as the setting for the paper and dice game RuneQuest. This had a big enough following at its heyday that it helped people take a look at the game. Really though I wanted to use the setting to help make the game incredibly rich. There was a lot of great material that we didn't have to write.

We tried hard to make all the lore approachable, starting with the interactive backstory. Your game advisors point out relevant facts. If the game requires you to know lore, we make sure it's available, as an easily digested summary as well as detail. But Greg agreed that the needs of the game came first, so there were a few areas where we made minor changes.

"at the time we were working on King of Dragon Pass for iPhone, the download would have been too large for the Android store"

Based on player feedback, we got it right. We introduced a lot of people to Glorantha, some of them excited enough to call from Finland to rave about the myths-back when long distance was still a thing. So while we considered other settings for our next game, we decided to further explore Glorantha in Six Ages.

King of Dragon Pass feels like a design sweet spot. It is an unusual mixture of strategy, simulation, and role-playing game, with a unique focus on characters and storytelling. The gameplay is very suited to its setting, and it all just works. How did you approach that, and how hard was it to get that right?

David Dunham: I know Greg Stafford and I bounced ideas back and forth, but my core idea was always to tell a multi-generational story. So the game revolves around story choices, and the strategy game exists to support them. The story side didn't seem hard, though it helped to have Robin Laws, a writer who knew games.

The biggest problem was probably that the story is emergent. Until the game was up and running, it was hard to know how well the pieces fit together, both in terms of things like making sure the livestock economy worked, and whether it was fun for long periods.

Another problem was that once something was in, it was hard to take out. When I adapted the game for iOS, I was able to remove some less interesting or less important choices (and even one or two that turned out to do nothing at all). With such a large game, with the implementation spread between all the script files and the underlying economic engine, I wasn't able to streamline as much as I had hoped I might.

Do you have any opinion on why more people haven't tried to mix strategy/management gameplay with storytelling like KoDP?

David Dunham: You can find any number of articles by writers pleading for game companies to bring them on early in the process. So there's an industry tradition of not prioritizing story. And I've worked on quite a few games that had zero need for story, since they were driven purely by their mechanics. Lots of teams don't even have a writer. Making story the primary focus would be very risky at a lot of studios, I suspect.

Games also tend to be marketed by numbers ("200 unique upgradeable weapons" or "hundreds of additional cards"), and story is usually hard to quantify. "Now with three stunning plot reversals" just doesn't cut it. As usual, King of Dragon Pass is an exception here. We can brag about our 575 interactive scenes, since this is a statistic that impacts the actual feature of replayability.

"Lots of teams don't even have a writer. Making story the primary focus would be very risky at a lot of studios, I suspect"

You've told me you don't want to talk about Six Ages, the sequel to King of Dragon Pass that you are currently working on, because it is still too early. What are your thoughts on building buzz about games?

David Dunham: This gets back to the very early days of King of Dragon Pass. I mentioned it to my friend Al Tommervik, who asked me not to tell him about it, but to make it and show him. The idea was that by simply sharing the idea, I might get enough satisfaction that I wouldn't follow through.

I think this is pretty good advice for creative people in general. On the other hand, the advice for indies to start marketing as early as possible also seems good. And many indie developers are very transparent about their development process, partly as a way to help generate buzz. How to balance all of this?

I'm hoping to do Six Ages in less time than King of Dragon Pass, despite having a smaller team, but it's still a much more ambitious project than a typical indie game. I believe that building buzz for a product that doesn't have any specific release date is going to be largely wasted. Who will remember it in a year or even two?

And I'm a fan of "show, don't tell." A lot of the progress on the game so far is pretty abstract. It's exciting to me that I can specify much more of the game with data instead of custom code, but KoDP fans don't seem as interested. So I want to wait until there's more of the actual game ready.

A final factor is to under-promise and over-deliver. For example, the new Apple TV certainly seems like it would work for a game that is largely about making story choices, and which can be played collaboratively. But I haven't looked at the specifics at all, so it would be a mistake to say anything. (By the way, Apple TV is not only not a promise, but a stand-in for other areas I don't want to promise until I can deliver.)

But once we have a reasonable idea of when we might be done, we will certainly start showing!